It intelligently matches some very fine old master drawings with engravings of the works for which they were studies, thus not only helping to understand the purpose and destination of these drawings, but also to ponder the process by which unique, and in the case of frescoes, fixed paintings could be published and disseminated through the medium of printmaking.

Most of the works in this exhibition are loans from the National Gallery of Victoria and, as I mentioned in the original review, this is an example of the way that the NGV has fostered the development of Victoria’s outstanding network of regional galleries. The Art Gallery of NSW should be doing the same thing, especially as the quality of regional galleries in this state, and of their collections, falls far short of those to the south.

Instead, the AGNSW has been almost entirely bound up in its own futile concerns, trying to turn itself into a contemporary gallery, and building a rambling but misconceived and poorly designed new wing. And having embarked on this project without adequate funds to operate it, the AGNSW is now in financial difficulties, as was reported in early February but predicted by insiders for the last couple of years. This whole project, from initial conception to design and execution, is testament to poor governance at the level of the gallery as well as a lack of strategic vision at the level of State Government.

But to return to Hamilton, the very quality of the exhibition raises some important questions. The first of these, obviously enough, is that Hamilton is a long way from Melbourne and even more remote if you are from elsewhere. It is a good thing to take exhibitions of this calibre to locations beyond the immediate vicinity of a capital city. But it is surprising to find that there are no plans to show the exhibition in Melbourne or take it on a regional tour.

It is odd to mount such a fine exhibition and not make it accessible to a wider audience. Equally significant, however, is what made it possible for the NGV to lend works of such quality in the first place, namely that so much of the NGV itself is currently taken up with its Triennial, which represents a diametrically opposite approach to the selection, curation and exhibition of art.

The Triennial is a populist circus. Outside, a massive poster with Yoko Ono’s declaration, “I love you Earth”, reminds us just how cheap talk is in the art world. Inside, you are met in the foyer by a couple of colossal figures, one of which is texting on a mobile phone (it’s hard not to think of Yoko Ono composing her “artwork”). The bathos is deliberate of course, and can be construed as either a reflection on mobile addiction or a comment on the banality of most public sculpture, but either way the contrast between the overbearing size of the figures and the triviality of both form and subject is inescapable.

If these mechanically produced objects – aesthetically speaking more like giant promotional store dummies than sculptures – were installed in a permanent place, the triviality would be unbearable; but they are temporary and only meant to be glanced at in passing, or used as a background for selfies or snaps to be posted on social media.

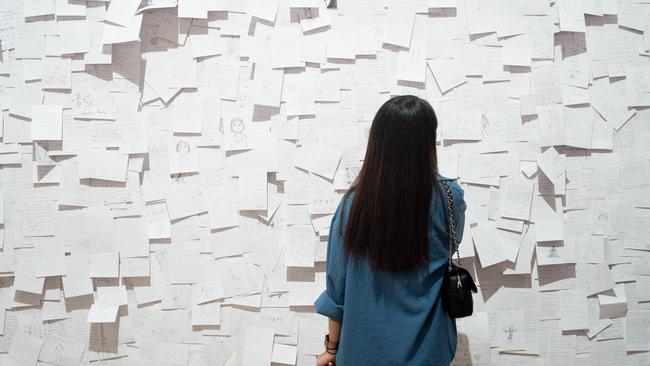

They form an appropriate introduction to an exhibition that is essentially about superficial sensation, surprise, “immersive” environments, and perhaps most importantly photo opportunities in an age when everyone is the consumer of their own endlessly repeated self-imaging.

There’s something for everyone, even art you can walk on, grotesque faces that carpet the floor of one gallery as well as its walls. There are rooms full of colourful video installations and even one set in the café to entertain you over lunch. All of these are designed to address visitors who essentially walk past them, glancing as they go. There are of course hyper-realistic “sculptures”, one of a man painting a broad stroke in what looks like house-paint on a white canvas; no doubt many people think this is what a painter actually does.

Some installations are subtler and more thoughtful, like a work that evokes the damage done to the environment in Mexico in the quest to satisfy North America’s hunger for avocadoes. This is the kind of work which would be interesting to visit on its own but suffers from the cacophony of too many rival displays, too much noise, too much distraction, and not enough attention. An installation that reproduces a classroom with dinosaurs perched on the chairs typically produces a brief impression of incongruity but conveys no deeper sense of poetic resolution.

A collective work about life in overcrowded global cities is made up of projections on hanging screens, crowded into a large space, perhaps to evoke the impression of stifling proximity and sensory overload in these monstrous urban agglomerations, but a short inspection of the work didn’t offer any enlightenment about a world we know all too well.

The most intriguing work – perhaps indeed the only work that could properly be called intriguing – was not actually art in any conventional sense, but rather a demonstration of new robotic technology. This was a kind of pen holding a couple of robotic dogs, one headless and the other with a mechanical head on an articulated neck and a mouth that appeared to be designed to pick things up. Curiously, the hind legs are fitted backwards: that is to say, while the elbows and knees of all mammals bend towards each other when they are on all fours, here the hind legs are the same as the forelegs, and thus with their knees pointing backwards. In any case they are sinister creatures, especially when we think how easily they could be armed and used in warfare.

Upstairs, more works have been installed a

mong the permanent hangings – thus explaining the need to remove so many pictures from these rooms – and no doubt the aim is partly to disconcert and shock, and partly to induce the crowds who have come for the circus to encounter more serious works that they have never looked carefully at, or even seen before.

Unfortunately nothing slows down the relentlessly drifting crowd, and the incompatible aesthetics of the collection works and those of the temporary exhibition make it hard to attend to either; in one room, for example, a lot of rather indifferent painted cloths hang from the roof opposite paintings by Constable; in the salon-hung room of smaller 19th-century pictures, giant leaves and various other objects draw attention away from the pictures but fail to hold our interest.

The exhibition was crowded on the Sunday I visited, no doubt delighting managers with their eye on the KPIs of attendance figures, but the futility of the whole thing was, if not surprising, still striking after the remarkable exhibition I had seen only the day before in Hamilton. That, in stark contrast, is an exhibition that invites slow and careful looking at works, and that rewards the viewer’s attention and patience with delight, discovery and insight.

It is an experience that makes you think, inspires curiosity to learn more, and leaves durable impressions and memories. It is composed of carefully selected, compatible and complementary works that speak to each other in a complex dialogue of forms and ideas that stimulate the viewer’s own pleasure, sense of agency and active participation.

The Triennial, in contrast, is designed for visitors to drift passively through a series of superficial experiences that neither demand nor reward attention. Their utter disparity and deliberate heterogeneity make it impossible to engage with them in any overall way or to find patterns or common threads of meaning. It is expressly designed as a fractured and fragmented experience, which serves to disguise the reality that few of these works are worthy of sustained attention in any case. As I observed earlier, the audience wanders past one display after another like desultory teenagers scrolling through Instagram.

In other words, the Triennial is art turned into junk food, “prolefeed” masquerading as contemporary art. And like junk food, it’s all salt, fat and sugar with no real nutrition. There’s little for the viewer to chew on, and the structure of the exhibition makes digestion inconceivable in any case. It is the sort of show that provides an overload of skin-deep stimulation and leaves you with nothing when you depart; you have seen nothing, learnt nothing and are left with no enduring impressions or memories.

So what does this all mean? Why is a good and valuable exhibition exiled to the country, while the people of Melbourne are fed such populist rubbish? It is hard not to feel that this reflects a general change in gallery audiences, which I have commented on before. Audiences seem to have a shorter and shorter attention span – no doubt as a result of the hyperactive and distracted world of electronic media – and both contemporary art and gallery managements in general seem to be pandering to this chronic distraction.

The NGV is obviously going to get more bodies through the door with the Triennial than with Emerging from Darkness, but that should not be an end in itself. State galleries, like museums and libraries, have a duty to contribute to public education, in this case through helping their audiences develop knowledge, judgement and discrimination. It is better to mount an exhibition that proves enlightening for a few hundred people than one that is just a day out for thousands.

That may sound élitist to some, but it is really the contrary: intelligent exhibitions offer everyone access to high culture, just as a good system of education sets high standards but offers everyone a path to meet those standards. Real democracy is about making people better, not pandering to their worst and laziest instincts; and we have seen enough of populism recently to understand that it does not arise from a desire to help the people but from the instinct to exploit their fears and prejudices.

Populism in politics is not a form of democracy but akin to fascism; populism in art similarly encourages the passive consumption of sensation rather than critical reflection and active engagement. Instead of the qualities that make a free citizen, it encourages the stupefied and unfocused condition of the slaves of consumerism.

NGV Triennial National Gallery of Victoria to April 7

A substantial and, especially by today’s standards, exceptionally well conceived exhibition at Hamilton Gallery in Victoria’s Western District was reviewed here a few weeks ago. Emerging from Darkness, which runs for another month, includes important examples of baroque painting – some loans from private collections – as well as sculptures and a tapestry from the series of the triumphs of Alexander the Great, made after paintings by Charles Le Brun, chief painter of Louis XIV.