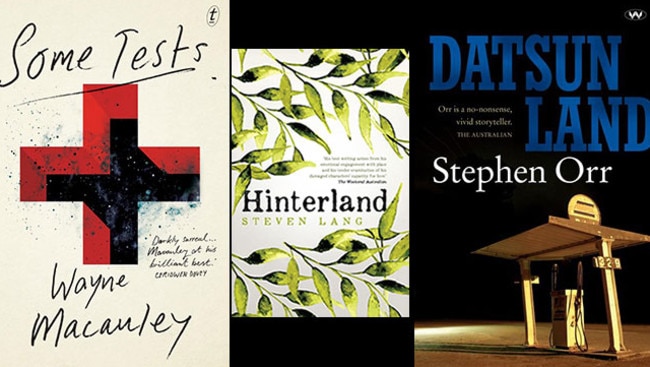

New novels by Wayne Macauley; Steven Lang, Stephen Orr

Wayne Macauley’s novels seek the answers to questions we’ve been asking ourselves for millennia.

If nothing else, one thing guaranteed in any Wayne Macauley work of fiction is that its surface is just that: a vehicle inside of which the real messages are carried. What makes Macauley’s novels exceptional is these messages are always vital — they are the messages we’ve been asking ourselves for millennia, in one way or another — but also the surface story-vehicle that carries these messages is compelling in its own right.

Think of The Cook, a tragic tale of a budding chef gone full feral, or Caravan Story, with its ghettoised artists just waiting for society to accept them, or the hopelessly hopeful frontierspeople in Blueprint for a Barbed-Wire Canoe trying to build a community against all odds.

His new novel, Some Tests, is ostensibly the account of one woman’s journey through the labyrinth of modern medical care. It takes place in a surreal suburban and then rural setting where vague specialists continue to refer her on, and on again, and on again, without revealing what is going on or even what may be wrong with her. This book is concerned with the inevitable loss that results from assuming responsibility for anyone’s life, especially your own.

All of Macauley’s critically underappreciated novels are often and largely about the battle of a single individual against the absolute impossibility of trying to take control of life. In Some Tests we are continually reminded that the modern world of endless choice is one giant illusion. Embracing these seeming choices, seeing them as a kind of salvation, is in fact just climbing into moment-to-moment imprisonment, making it easier for the jailer — that is, yourself.

The medical tests in the novel — the medical tests we all know, the ones readily available to us whenever we may feel askew — act as an allegory for the questions of existence, the tests of spirituality, of science, of philosophy. “The tests available these days are infinite and it is reasonable to expect that a person in your situation … will take up our offer of more, clinging perhaps to the hope that the next will provide the answers.”

One of the many doctors encountered puts it thus: “If no comfort is found in the next test, or the one after, how far do we go? To infinity?”

This same doctor, whose name is Panchal but we can call him Macauley, asks us directly: “How far do we go? When do we stop? The more faults we look for, the more we find. Deciding whether to have one more test and hold to the slim possibility of an answer — this is a problem that has grown exponentially with the many tests now available to us.”

If there’s a test really worth taking, a choice really worth making, it’s to read Some Tests, and all of Macauley’s writing, and see where you end up.

Steven Lang’s Hinterland has much in common with Macauley’s previous novel, Demons, which also hosts a bunch of variously immoral adults we are forced us to watch in real time as they pontificate, bicker and flirt. And Hinterland, like all Australian novels of its ilk, is drawing easy, albeit wrong, comparisons with Christos Tsiolkas’s The Slap, simply because of its broad issues-driven social realism punctuated by events relayed by a middle-class carousel of boomer characters who are all (often obnoxiously) given a chance to tell us their side of the story.

Lang’s novel tells of a small farming district town that recently has been transformed by a flood of tree-changers, retirees and wealthy developers and is having to decide whether a proposed dam is going to fix or ruin everything. The events are fairly clever in their construction and interweave well, but are just stages on which the various romantic and political dramas can play out: friends fighting, spouses cheating and dying, the works. This is a book of human beings.

Hinterland aims to interrogate humanity, or at least a small bubble in the swirls of humanity’s torrents and rapids, trying hard to capture something of our present moment, nationally and globally. It is manifestly “about” capitalism, environmentalism, political systems and the inevitable clashes of culture that occur between Western people with too much money and time and not much meaning in their lives. As one of its many narrator characters ponders when visiting and observing an elderly town resident, she is living “for who knows what reason. Although that could be said about most of us.”

Lang lives in Maleny, a picturesque back-country town in Queensland, much like the setting for his novel, the fictional Winderran, and he has some insight into the bustle and pettifogging that can smog a small, newly capitalised Australian burg.

His characters bitch and moan, both openly and inwardly, and we are present for the ingloriousness. There’s a distinct gender binary present in the novel, in more ways than one: Lang’s men are routinely awful throughout, and his women not awful in comparison but also not much of anything else, except definitely more corporeal (we are given much more information about their bodies and looks than we are the men). Any kind of Bechdel test this novel would not pass. Yes, the story of Hinterland may be one that is being played out across many Australian towns, but when rendered with no subversion, even subtle, or any deep-probing satire we are left to wonder: how more unreal social realism can Australian literature bear?

Lang is no literary slouch: his novel An Accidental Terrorist won premiers’ literary awards in Queensland and NSW, and his 88 Lines about 44 Women was shortlisted for the Christina Stead Prize and the Queensland Premier’s Literary Award for fiction. But maybe Australia and its literature is slowly progressing. Maybe the increasing diversity we’re seeing at all levels of Australian writing is improving the quality and subject matter of Australian novels.

And maybe Hinterland feels more defunct because of this. (To suggest this in a book review that appraises books by three white male authors, a review commissioned by a white male editor and written by a white male writer, feels impudent, but these hypotheses are posed with full sincerity.) Maybe Hinterland, full of characters that are definitely just characters, never at risk of seeming like real people, and a conclusion that is much too abrupt in comparison to the slow build-up before it, is an example of Australian literature that once may have won awards. But most likely not any more.

If you’re thinking the various narrative events of Hinterland sound a bit cheerless, then you’re going to want to stay well away from Stephen Orr’s new short fiction collection Datsunland. It would be a challenge to name another set of stories with subject matter this demoralising. But if you do stay away, then you’re going to miss an intensely interesting and varied consideration of Australian masculinity in all its colourful plumage, even if most of these colours are toxic: shit-brown and hollow-grey and dark, bottomless black.

All of the stories are set in South Australia, some in contemporary times, but most at different points throughout recent history. Here’s a list of just a handful of the 14 stories in this collection: an Indian doctor tricked into working in Coober Pedy falls deep into despair; the life of a father grieving for the loss of his son revolves entirely around whether he will kill himself; a boy helping build a ship becomes trapped in its hull and dies; an elderly, culturally conservative man spends his savings on making a video to “fix” the world and murders someone on camera to make his point; an awful blow-by-blow depiction of the ongoing domestic abuse of a young boy; ad nauseam (and expect actual nausea, so uncompromising are these stories).

There is beauty in this bleakness, though. When Orr nails it, his writing is piercing, brutal, powerful, both in respect to his unflinching gaze and his wielding of plain English like a weapon. You as a reader will survive, but not without blunt force trauma to show for it.

Several of Orr’s stories fall flat, and not just in a tonal way: the events of these few unsuccessful stories do not flow; some are too rushed, and one or two are simply confusing. It’s a shame for someone with Orr’s vision and skill. As one of his ubiquitous male characters ruminates, “A story was more real than the thing, after all. The thing just happened, but the story you could control.”

At 115 pages, Orr’s final and titular piece Datsunland is a novella — indeed, it featured in the most recent novella edition of literary journal Griffith Review — and is the best work of the collection. Reminiscent of another terrific short novel of adolescence, music and broken dreams by a South Australian writer, Peter Goldsworthy’s Maestro, Datsunland tells the story of whip-smart and big-dreaming schoolboy Charlie and his jaded and totally without-hope music teacher William.

In an interview about this work, Orr said: “Datsuns are the dream, underpowered, bow-legged, ripped vinyl, basic (and broken) gauges on a cracked dashboard. Just like William and Charlie: plain-looking cars that just keep going.” The keeping-on-going is Australian masculinity at its best, and its worst, and Datsunland gives us both.

Orr is not a writer interested in pasting over cracks, not interested in lives lived easy. It is Charlie’s father’s take on existence that gives us as good a summation as any of the outlook of the Orr’s stories: “How the bits are just part of the whole, and how this drama of colour and movement is over before you know it’s begun.”

Sam Cooney is a writer and publisher at The Lifted Brow.

Some Tests

By Wayne Macauley

Text Publishing, 256pp, $29.99

Hinterland

By Steven Lang

UQP, 346pp, $29.95

Datsunland

By Stephen Orr

Wakefield Press, 312pp, $29.95

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout