New exhibition reveals the art of photography in its truest form

Facebook and Instagram dominate everyday photography, an art form once treasured as a means of recording the past.

Photographs, especially of people, are almost always nostalgic, inevitably reminding us of the passing of time. Family photographic albums can be especially sad, filled with childhood images of now middle-aged people, or happy family pictures of others who have long ago passed away.

But photo albums belonged to a time when pictures had to be developed and printed, and then physically stored somewhere safe. In the last decade and a half – an insignificant interval of time in the sweep of history, and yet one that has changed many habits irreversibly – the advent of the smartphone has completely transformed our habits in photography as in many other areas.

Photos no longer have to be printed, but can be stored in digital form, so we don’t need to be selective any more about which shots to enlarge and preserve from a contact sheet; at the same time, because we are not using rolls of film with a finite set of shots, we have become far more promiscuous in our photographic habits. In combination, these two factors have resulted in a massive inflation in the number of photographic images that now exist in the world in virtual form at least; it is quite likely that more shots have been taken and digitally stored in the last 20 years than in the whole previous history of photography.

But although hardly anyone appears to be collecting family photos in albums any more, the interest in pictures from the past is as strong as ever. Facebook, for example, has an algorithm that regularly brings up photos originally posted by users one, two or three years earlier. This, we are told, is because Facebook “cares about our memories”. It seems that online life will increasingly be curated and designed for us by caring algorithms.

But users themselves, over the last couple of years, have increasingly taken to posting pictures of their carefree or misspent youth, inevitably eliciting a rush of replies and comments from their friends, although getting the tone right can be hard: “you were so gorgeous” is a little awkward, while “you haven’t changed a bit” is almost always disingenuous.

The reason photographs of people are melancholy, of course, is that they are records of individuals snapped at a particular moment in their slow but ineluctable progress through time and entropy. We don’t feel this at all about figures in paintings, because they have been removed from this current and given a role to play in a more timeless pattern of human meanings.

This is clearly the case in a narrative painting where the models the artist initially drew from have been turned into historical or mythological figures. But it is even true, interestingly enough, in portraits. In Degas’s early masterpiece The Bellelli Family (1858-67), for example, the sitters are his aunt Laura (his father’s sister), her husband Baron Gennaro Bellelli and their two daughters; but we are not for a moment tempted to feel sadness at their ageing, or to wonder about their subsequent fate as individuals. Instead they are transformed, transfigured one might almost say, into a memorable and complex composition, into the image of a psychological drama as subtle as a novel. They have been lifted out of time and rendered perennial.

There is a final twist to the melancholy of photographs: contrary to what one might assume, it is more acute with recent pictures than with older ones. In the latter case, we are simply glad to have records of an otherwise lost past; whereas those images that record a world in which the audience participated and of which they have personal memories can be ineffably sad.

Such is the case with the National Library’s exhibition of documentary photography, most of which covers the last two or three decades of last century. A notable example is a photo by Rennie Ellis (1940-2003), Hare Krishna, Kings Cross (c. 1970-71): a group of Hare Krishna devotees are seen chanting in front of a bank, while in front a stony-faced old crone in dark glasses passes grimly by, clutching a shopping-trolley, and followed by a young thug who is evidently up to no good.

Where are they now? Well, as it happens, a friend recognised all of the Hare Krishna group, whom he knew personally in the 1970s. The old crone? No doubt long dead. The young thug? Perhaps in prison, or perhaps reformed and now retired, a fat old man watching television somewhere in a distant suburb.

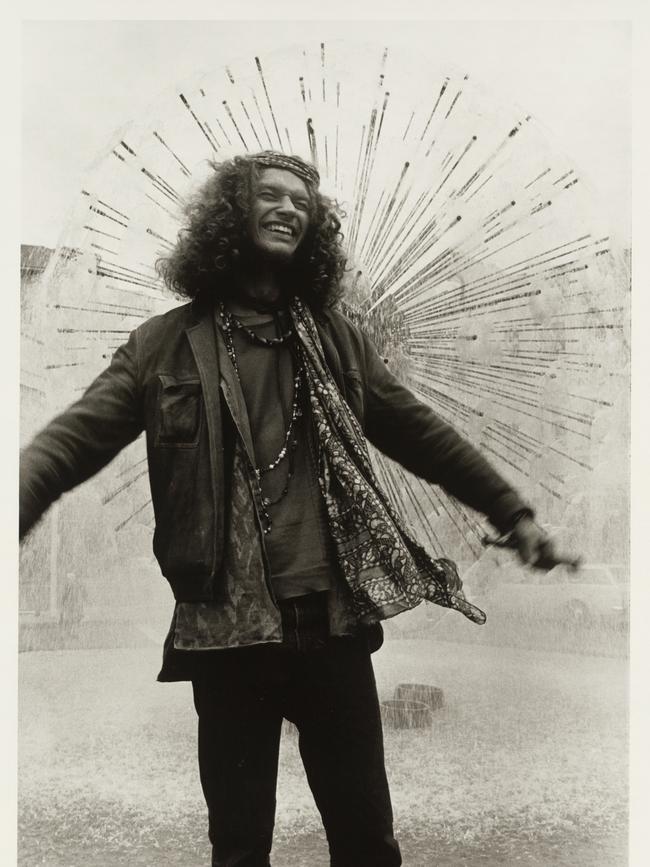

One could ask the same question about the young “sharpies” in Ellis’s photograph of the same title (1973), members of the same Melbourne gang subculture commemorated in a couple of Carol Jerrems’s most memorable pictures of the time. Back in Sydney, Ellis’s Hippie, Kings Cross (1970-71) is particularly poignant, with its gesture of youthful joy and rebellion matched by the exuberance of the El Alamein fountain behind.

Some other pictures are of less engaging individuals, like Women on the Palm Beach bus, Sydney (c. 1975) by Bruce Howard (b. 1936). On the left are two desiccated old women still wearing the hats and gloves of a more gracious, if formal time, but somehow entirely without the grace, as though fossilised in a custom no longer understood. On the right are two unremarkable young women in the dress of the day and dark glasses. Each group seems to live enclosed in its own sterile cultural bubble without curiosity or openness to the broader world around them.

Another picture, by Robert McFarlane (b. 1942), shows three girls in a cafe at Kings Cafe, Sydney (1981) – perhaps in Kings Cross? – but is particularly remarkable when we think of the photographic milieu in which young girls of the same kind live today. They are pleasant and spontaneous enough, but compared to today’s social media world, in which everything has to be curated and polished, they look scruffy, plain, uncared for.

But these young women were, at the time, simply interrupting their conversation, coffee, cigarettes, to pose momentarily for the photographer. They had no idea where the picture might end up, but at most it would be in an exhibition and perhaps ultimately in a book. It was not going to be published online directly to an audience of “friends” and “followers”. And of course none of that existed: that dimension of reality now called “online” had not yet come into being. Today girls like this spend half their time at a cafe taking selfies and pictures of each other solely for the purposes of posting them; instead of the photo recording the occasion, the occasion has been reduced to a photo-shoot for posting into the illusory maelstrom of the online universe.

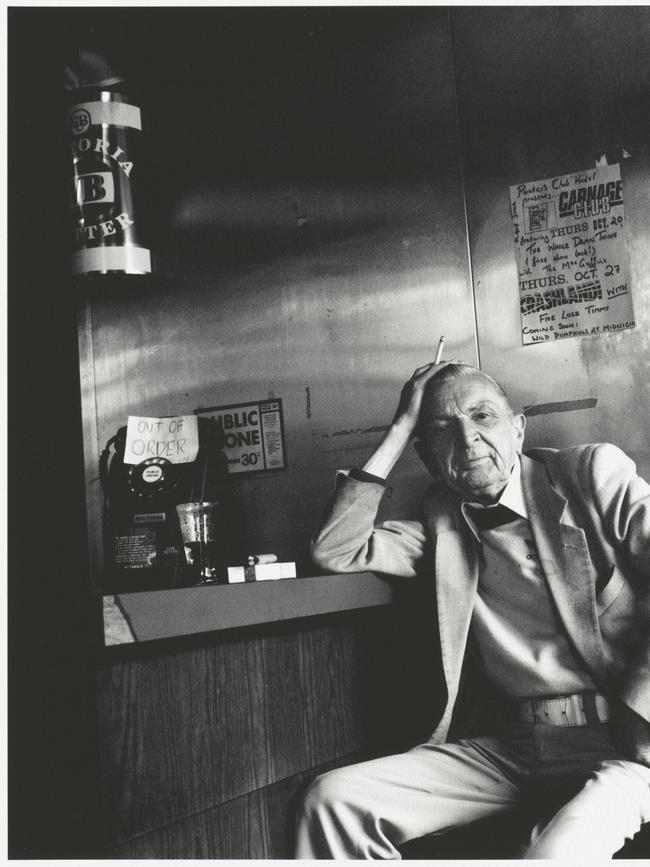

A final pair of portraits in this first section of the exhibition, devoted to “people”, makes an interesting contrast. One is The Real Australian: portrait of a man in a bar, Brunswick Street, Fitzroy (1990) by Maggie Diaz (1925-2016), and the other, a year earlier, is Travelling camel man, Wentworth Region, NSW, 1989 by Jeff Carter (1928-2010).

The first of these is a singularly depressing picture of a solitary man in late middle age sitting with drink and cigarette in a seedy pub; in the background is a public phone with a handwritten sign “out of order”. If he still manages to look less derelict than his contemporary equivalent, it is because he is slim and comparatively well-dressed; this was before the obesity epidemic and also before both men and women thought it was acceptable to go out in public in mass-produced “leisure wear”.

Jeff Carter’s portrait of an outback cameleer, in contrast, does not elicit the melancholy associations of so many other pictures I have mentioned. There is something timeless about his person, his dress and his action – the photo could almost have been taken a century earlier – and not only timeless but impersonal. It is as though all the others were bogged in a tawdry culture of egoism without self-awareness and consumerism without higher aspirations, while the cameleer is free of ego, living in an ancient culture still attuned to a spiritual vision of the world.

The next section in the exhibition is devoted to “play”, followed by sections on “the natural environment”, “work” and “the built environment”. There is plenty in these sections that is fairly disheartening too, particularly in looking back on the nullity of mass culture that is evoked in pictures like Star City Casino (after Breughel) 1998 by Anne Zahalka (b. 1957).

Images of work remind us how hard it is to design humane environments for the kind of work that is done by hundreds of clerks – now called executives – at rows of desks. The worst is a room full of workers at a call centre in Melbourne in 2006 by Dave Tacon (b. 1976); this was just before the invention of the smartphone and the eruption of social media, but all the clerks are sitting in tiny cubicles in front of a PC, a sterile environment which one woman has tried to personalise by piling dolls on top of her monitor.

The then-new BHP offices in Melbourne (1973) photographed by Wolfgang Sievers (1913-2007) and the more recent NAB building in Melbourne’s docklands (2004) by John Gollings (b. 1944) are both less obviously oppressive yet do little to mitigate the dehumanising effect of mass office work environments.

If all this sounds grim, there are brighter moments, like a charming picture of Children floating on board, Yirrkala, Northern Territory (1989) by Mervyn Horton (b. 1945) and Jeff Carter’s picture of little boys learning to play rugby in Berry. Rennie Ellis again has a couple of memorable pictures, one of a crowd excited by the performance of a rock guitarist (1978) and the other of Surfer boys and girls on beach, Lorne, Victoria (1975) where amusingly all the boys are lying on the sand in one row and all the girls separately opposite them. One of the best and most engaging shots in the exhibition is of a dog leaping on to the back of a hay truck by Bruce Postle (b. 1940).

Among the images of the natural and built environments, there are several that record new building projects, and several too that document the damage done to the environment by mining operations. The most beautiful ones, however, are landscapes which strictly go beyond the boundaries of the documentary category. Of these, one of the oldest and most evocative is The Lonely road (1974) by Olive Cotton (1911-2003).

Most remarkable as landscapes, however, are three photographs by Peter Dombrovskis (1945-96), including Morning light on little horn, Cradle Mountain – Lake St Clair National Park, Tasmania (1995) and perhaps above all Morning Mist, Rock Island bend, Franklin River, Tasmania (1979), which has a play of rock and water, and an elusive poetry reminiscent of a Chinese landscape.

Viewfinder: Photography from the 1970s to now

National Library of Australia, until April 30

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout