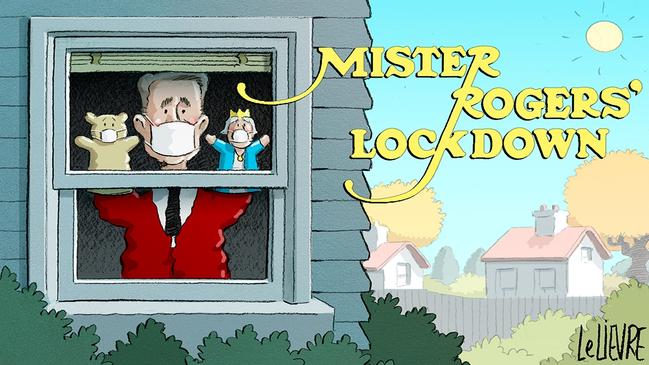

Mr Rogers’ neighbourhood anything but dull

The Tom Hanks film, A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood, had its brief cinema run at the end of last year. The picture is a gem.

“It’s a beautiful day in the neighbourhood, a neighbourly day in the beauty-hood.”

These words are a little ditty and mostly little ditties that take up uninvited residence in your head are acutely annoying.

But these words are surprisingly welcome. I have come to love them.

They feature as a kind of anthem in the Tom Hanks film A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood, which had its brief cinema run at the end of last year.

This picture is a gem. I watched it on an international flight several weeks ago, before travel bans. I thought it might be bland and dull. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

It concerns the life and work of Fred Rogers, a mildly conservative, soft-spoken Presbyterian minister who went into children’s television and created an institution, Mr Rogers’ Neighbourhood, which ran from the late 60s to 2001.

It was TV directed at kids from preschool to pre-teen. Unlike almost any other such show, it dealt with moral development in young children, and confronted tough issues like death, anger and loss.

And yet everything about the TV show was positive and warm and good.

After I got back to Australia I ran into Bob Darrenbecker, an American who is now the dean at Melbourne’s Trinity College Theological School. He grew up in Syracuse, New York, and told me that Fred Rogers was the most important adult in his life, from the age of about five to 11, after his parents.

Rogers was a lifelong Republican and moderate conservative but never intruded politics into his public persona. Everything he said and did was based on Christianity, but he interlaced it subtly. It underlaid everything. He didn’t hit viewers over the head with it.

I’m not quite sure why this is so, but one of the hardest things in art is to make a normal, good person interesting. Art finds evil easy, and heroic goodness, wartime sacrifice or the like, is dramatic and readily usable, in film especially.

But goodness, real goodness, in a regular, undramatic life is challenging for the arts.

Rogers was widely popular in the US but you don’t have to know that to appreciate this film. It is based on the unlikely friendship that developed between Rogers and an Esquire writer sent to profile him.

This is semi-fictionalised to structure a dramatic arc, but it’s basically true. The journalist was hard-bitten and cynical — how remarkable for a journalist! — and thought over time he could puncture some facade of Rogers.

But it turned out there was no facade. Instead, Rogers helped him put his own life back together. The original Esquire piece is itself fantastic.

The journalist hates his dad. Rogers at one point says to him, just remember that your dad was a big part of making you the good man you are today. Rogers’s favourite prayer, his whole attitude to life, is contained in three words: thank you, God.

Rogers is not presented as perfect. He has his own struggles and prays, reads scripture and swims every day to help channel his energies. But he is always kind.

The film makes the journalist the protagonist, but Rogers is always there. His goodness thus remains a small mystery and all the problems of a biopic are avoided.

Though the film is engrossing, there is also a beautiful, quiet, meditative quality about it. In these troubled times, beauty, quiet and restraint are the rarest qualities, and in this case they are part of a superior work of art, one which sustains the spirit.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout