Motherhood statement: Australian poets write of kin and country

Relationships, family and culture are at the heart of the poems by indigenous poet Ali Cobby Eckermann.

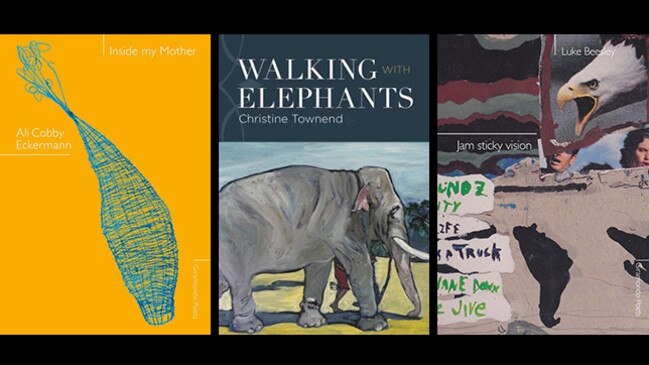

Ali Cobby Eckermann’s Inside my Mother (Giramondo, 104pp, $24) is a reminder that family, at the heart of everyone’s personal story, is also at the heart of our nation’s history. For the Stolen Generations, as for others who have survived the trauma of separation, the word family has no easy meaning.

In her 2013 memoir Too Afraid to Cry, Eckermann told of her experience, one of the many stories of the breakup of families that has resulted from the forced removal of children, as well as from extreme social disruption, and the poverty brought about by institutionalised and casual discrimination.

Inside My Mother is a more kaleidoscopic account of Eckermann finding her mother and other relatives, and of the ongoing process of mothering her own children. She writes about the pain of separation and the difficulties, as well as the joys and satisfactions, of building connection.

The poems are neither depressing nor fatuously uplifting. They are considered, thoughtful, undulating, so close you can feel breath, then panning out for the bird’s eye view. She writes in such a way that readers with varying degrees of insight into the cultural place from which she writes can find a way to read the poems.

Her images are clear and succinct, but also dense, as a seed or bulb is dense with its future as a tree or flower. In the poem Tjukurrpa, fragments of a birthing story are told:

a carry basket is woven from reeds

baskets are woven with story

baskets are woven with song

my basket is heavy with history

out of sight like superstition

The contrast of story and song with history and superstition contained in the image of the basket is a succinct description of what it might be like to experience a complicated kind of belonging, though the speaker in this poem is securely located in terms of both land and kinship. The short couplets are visual echoes of the carry basket, an object simultaneously pragmatic and symbolic, as is Eckermann’s approach to poetry.

This poetry is intended to communicate, and to provoke an emotional response from the reader. Substantially, Eckermann’s language is inventive but not difficult to follow. Once or twice a piece of wordplay falls flat or a last line summarises to the extent that the poem loses the fishhook ability to catch and pull at you after you’ve finished reading.

The tension around how much to say is inherent to writing poetry that is intended to communicate clearly. Lines that, for one reader, are enjoyably comprehensible will, for another, lack complexity or resonance. Eckermann’s sincerity and the quality of her writing mean the emotional power of her work can’t be avoided. This provocation of emotion is deliberate, a strategy used in the service of the work she does to further the process of healing for those who share her experience of trauma, and to instil insight and understanding into those readers who have not encountered or engaged with the kinds of experience she writes about.

The poems in Inside my Mother focus on relationships, family and culture. Eckermann writes about pain, sadness and rupture, but she is also writing about survival and healing. Implicit in all this is a political context the reader is left to interpret for themselves.

Christine Townend is another who writes with an intention to communicate persuasively with the reader, her interest being in our kinship with animals. Townend has dedicated her life to the care of animals and to advocating for animal rights. She is a co-founder of Animals Australia, has run for parliament and lived in India, working in an animal shelter in Jaipur before founding two other animal shelters in that country.

She has written a novel and several works of nonfiction, but Walking with Elephants (Island Press, 96pp, $20) is her first book of poetry. Townend’s poetry goes beyond the close study and observation of the more traditional nature poet. The animal is always the point of the poem, rather than a metaphor or an opportunity to examine a feeling or idea. What can be surprising, even challenging, in this formally conventional work is the position in which she places herself in relation to her fellow creatures.

Even in The Dalai Llama’s Brother’s Dog, a suspenseful description of being bitten by a dog, she maintains her philosophical position, though the poem has more to offer than that:

The world went through a keyhole.

I was in church vaults

with bare feet sounding softly on old tiles.

The poem hurtles along, as compulsive as any thriller, with its vivid descriptions of the narrator’s own physical experience.

Townend writes with just as much conviction from the animal’s point of view, seeking to describe how the subject of her poem experiences the world. How successful such an attempt can be is a matter for philosophical, rather than aesthetic argument, and is beside the point when Townend’s intention is to present her readers with opportunities for empathy with species other than our own.

Luke Beesley favours surreal, collage-like, playful, sometimes punning poetry in his book Jam Sticky Vision (Giramondo, 88pp, $24). He’s clearly a reader of other poets and a keen participant in cultural life, a film-goer, a music lover, of the alternative, art house kind.

Alongside the lyric poetry are prose poems, and his disrupted style is common to both forms. There are plenty of choc chips of interest that deserve to be enjoyed, though Beesley’s work at times could benefit from being cut back.

Even poetry that does not set out to make sense benefits from a varied dynamic, a sense of propulsion, or rhythmic power that turns the loose language and syntax into a patterned, engaging poem. When Beesley’s writing feels deliberate he can draw together a sharp, memorable phrase. The sound of the words is sometimes enough, as in the opening lines of Type Slowly:

Concrete walls were a backdrop to the panic

anorak she wore. Tuesday. In the present.

Quoting more lines won’t make more sense of this opening image, so let’s just enjoy that panic anorak, let it unzip into association, into memory and speculation. There are an uncountable number of reasons to write a poem. This may be one that has been written just for fun.

Ali Jane Smith is a poet and critic.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout