Melbourne exhibition hosts some of history’s most important tomes

This fascinating exhibition is built around a set of precious volumes lent by the British Library, and which were part of its Hebrew Manuscripts: Journeys of the written Word exhibition in 2020.

Luminous: A thousand years of Hebrew manuscripts

State Library of Victoria to April 1

Jews, Christians and Muslims are often referred to as “People of the Book”, “Ahl al-Kitab” in Arabic, alluding to the common basis of their religious beliefs in the Jewish Bible, the Talmud, which Christians call the Old Testament. Recognising the two older systems as precursors to their own, the Muslims granted certain privileges, including freedom of worship, to Jews and Christians within their dominions.

The importance of a set of canonic scriptures within these three related traditions sets them apart from all other cultures.

All civilisations have books of religious doctrine, scripture, wisdom and mythology, but elsewhere the canon is less consistent and more open-ended. The Greeks, for example, had Homer and Hesiod as well as the corpus of Homeric and other hymns, but Greek religious belief was always elastic and evolving; the Indians have a plethora of sacred books, from several related religious traditions; the Chinese have the ancient divinatory texts such as the I Ching, as well as the very different teachings of Confucius and Lao Tzu.

Only the People of the Book developed a strict canon in which every word, ascribed to divine revelation, was sacrosanct and in which commentaries could be built on commentaries to elucidate their meaning. Such a strict approach to scripture favoured stability and continuity, but it also gave rise to ultra-orthodox and fundamentalist thinking, which can only exist under these conditions.

The role of the Book in ensuring the continuity and survival of tradition cannot be overstated. During the dark centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire in Western Europe, books in general but the Bible in particular became not only the vehicle for culture and cohesion but almost the only vehicle for artistic expression, in the forms of calligraphy and illumination. In the Jewish and Islamic worlds there was an even greater emphasis on the writing of the Word, since images were largely prohibited by the Second Commandment.

Books are inherently portable, and we may think of the movement of books along the Silk Road and especially the migration of Indian sacred scriptures to China and beyond. But the point is perhaps even clearer when there is just one sacred text, carried by believers all over the world. Pre-literate cultures are often tethered to particular locations; but books allow culture and belief to be carried with us and implanted anywhere people settle.

The portability of culture is particularly striking when we look at the extraordinary history of the Jewish people. Considering the importance of the concept of the Promised Land in their tradition, they have survived for much of their history in exile from it, until their return to their ancestral homeland in the course of the last century. Indeed periods of exile from the land of Israel, as during the Babylonian Captivity of the 6th century BC, only seem to have strengthened the sense of Jewish identity.

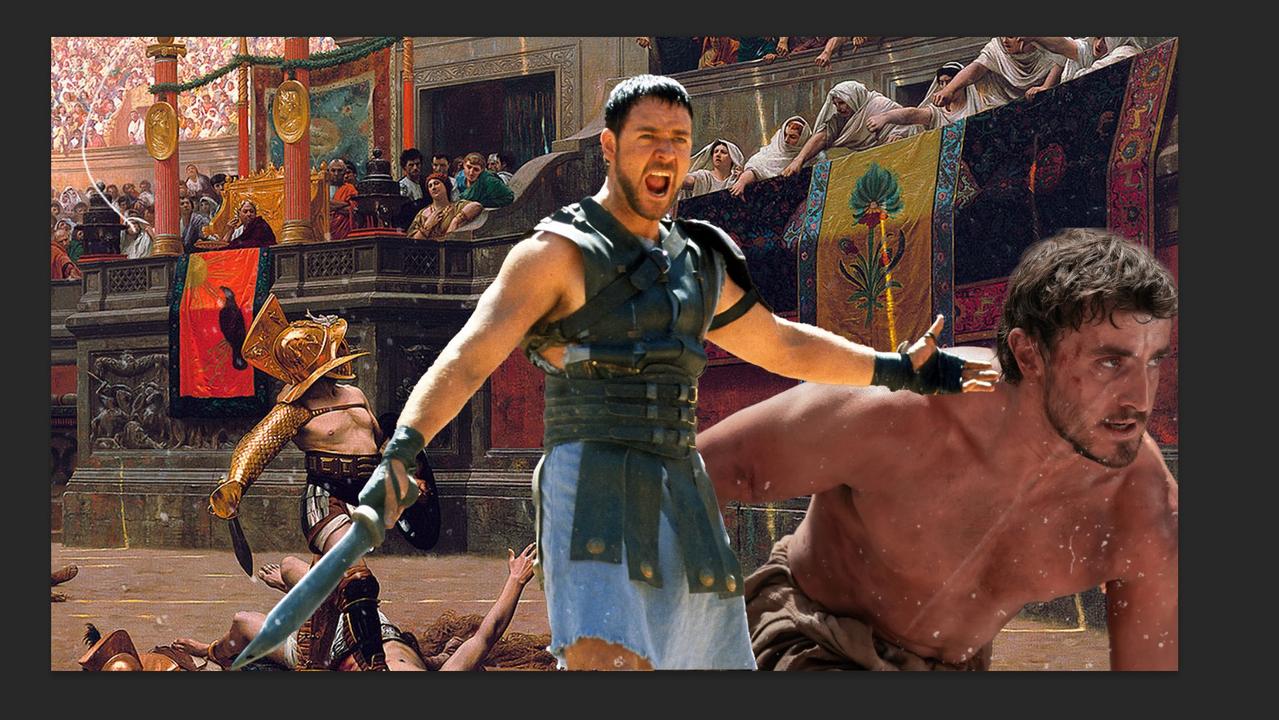

But even in Israel itself, the Jewish people lived almost always under foreign dominion – whether of the Assyrians, the Babylonians, the Persians, the Hellenistic Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs or the Turks; there was a short interval of relative independence in the second and first century BC, when Judaea was still nominally part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Dynasty of Syria, before it became a client state of Rome under Herod, and then a directly governed province.

After the diaspora that began after the destruction of the temple by Titus in 70 AD and accelerated after Hadrian’s suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 132, the Jews of Israel spread throughout the Roman Empire; there were already very large communities in cities such as Alexandria, where the Bible had been translated from Hebrew into Greek around 250 BC, but now they moved much further afield. Centuries later, some of these communities found themselves ruled by Arabs, others by various Christian states in medieval Europe; some had even ventured as far as East Asia. Life under these foreign masters was not always easy, and Jews faced the same conundrums they had already known under foreign rule in antiquity: how to maintain their own identity while complying with the laws of the states in which they found themselves. And this was particularly difficult for them, for, unlike many peoples who over the centuries have simply adopted the religions and customs of whoever happened to conquer them, the Jews had very strict and demanding codes of laws of their own.

In addition they faced periodic persecution, antisemitic riots, and sometimes expulsions of whole communities. Christians knew that their religion was founded on Judaism and that their Old Testament came from this tradition. But they believed that the birth of Christ had heralded a new dispensation and that the Jews were stubbornly persisting in an obsolete set of beliefs. Many also blamed the Jews for putting Christ to death, although in strict Christian theology this was necessary to bring salvation into the world.

Through all these difficulties, expulsions, pogroms and attempts at genocide, the Jews have not only survived, but maintained their beliefs, their identity and their very people in a way that is no doubt unique. Other ancient peoples have dissolved into a constant process of intermarriage with other ethnic groups; only the Jews are substantially still the same people they were in antiquity, a point that Marcel Proust, himself Jewish, makes about his Jewish character Bloch in a memorable passage in Remembrance of things past.

This fascinating exhibition is built around a set of 37 precious volumes lent by the British Library, and which were part of its Hebrew Manuscripts: Journeys of the written Word exhibition in 2020. These are supplemented by loans from the Jewish Museum of Australia and private collections, as well as works from the State Library of Victoria’s own Rare Book collection, and in particular from the David Halperin Collection. Halperin (1814-60) was a medical doctor trained in Constantinople who also took an interest in occultism and migrated to Australia in time for the Gold Rush where he tried unsuccessfully to use magic to locate gold deposits.

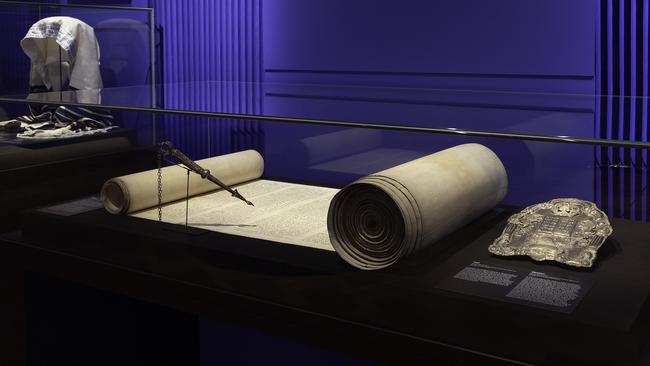

The biblical scriptures are represented by a handsome Torah scroll from the British Library which in itself speaks of the global diffusion of Jewish culture: it was copied in the 17th century in Kaifeng, in the heart of China, where a Jewish community had migrated from the Middle East in the 10th century. Around this are several displays that illustrate how the sacred scriptures are used in everyday life, and a video evokes the work of a senior scribe in checking and correcting manuscripts of the holy text.

There are of course no illustrations in this elegantly and precisely written, but austere manuscript. And yet elsewhere in the exhibition it is fascinating to see that marginal illustrations could apparently be acceptable if they took the form of figures composed of tiny words, ostensibly of textual commentary. These images, known as micrography, are akin to the so-called “technopaegnia” practised by some Hellenistic poets, or the calligrams of the modernist poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

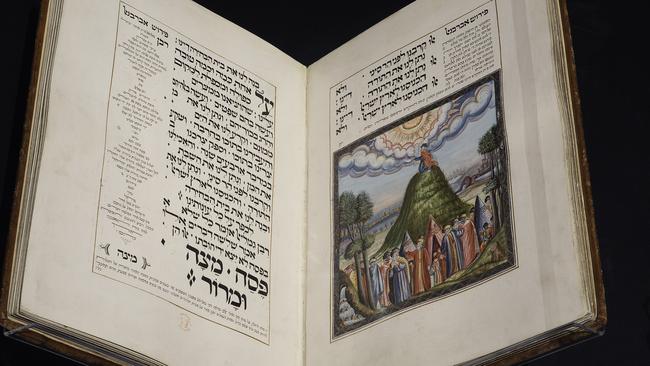

In later books and works less sacred than the Torah itself we find a number of remarkable illuminations, including an elaborate view of Moses bringing the tables of the Law down from Mt Sinai in an 18th century collection of prayers, and a charming illumination of animals in a Perek Shira, perhaps recalling the Indian tradition of the Panchatantra, which frequently appears in Arabic book illuminations, too.

The exhibition offers intriguing insights into the complex cultural interactions and exchanges between the Jewish people and the others among whom they lived, particularly in the East. Thus there are texts in Judaeo-Persian, Judaeo-Arabic and even Judaeo-Urdu, which effectively means stories and poems in Persian, Arabic or Urdu (the form of Hindustani mainly spoken today in Pakistan) and yet written in the Hebrew alphabet.

One of these texts, a treatise on mathematics, is written in Judaeo-Arabic and annotated in the margin in Arabic, giving some idea of the extraordinary crucible of linguistic and cultural exchange in this area. Hebrew itself had only been read by scholars since Hellenistic times, but the translation of Avicenna’s Canon medicinae into Hebrew endowed the language with a new medical vocabulary. Again, it gives some idea of the intellectual complexity of this time when we recall that Avicenna, as we call him, or Ibn Sina (980-1037), was a Persian scholar who synthesised the Greek medical knowledge of Galen with the philosophy of Aristotle and who wrote in Arabic, as the lingua franca of the Islamic world.

All of these texts are from Oriental, North African and Iberian authors, in other words from what is known as the Sephardic Jewish tradition, much of which subsequently, after the expulsions from Spain and Portugal at the end of the 15th century, relocated to England and Holland.

The central and eastern European Jewish tradition is known as Ashkenazi; and here there is also a book, written in Hebrew script, but in this case in Yiddish, which is an Ashkenazi dialect of German.

There are works by the principal Jewish philosopher of the middle ages, Maimonides, who like Avicenna and Averroes, the other great Islamic philosopher, was an Aristotelian, but Jewish intellectual life was more oriented to legalistic commentary than to philosophy, and over the centuries – as in the Islamic tradition – commentaries accumulated on commentaries. Unlike the Muslims, however, the Jews embraced printing when it was invented in the 15th century and one display shows the ingenious way that all the main commentaries could be laid out around the sacred text itself.

Among the many other remarkable things in this exhibition are several books on the mystical kabbalistic tradition in Judaism, which fascinated Christian intellectuals from Pico della Mirandola to Athanasius Kircher. And there are also equally important texts that bear witness to the difficulties under which Jewish populations lived: Hebrew texts were regularly subject to examination by censors to make sure they did not contain any anti-Christian ideas.

This process of censorship was usually carried out by Jews who had converted to Christianity, since there would have been very few Christians capable of reading Hebrew. So here, for example, we have a couple of 13th-century Hebrew texts, in an early 14th-century manuscript, annotated with several censors’ signatures. A late 16th century work by another convert, here in a 17th century edition, lists about 450 books considered blasphemous.

Finally, there is an account by Rabbi Ishmael Hanina of his interrogation and torture in Bologna in 1568, during the persecution ordered by Pope Pius V, the year before the Jews were expelled from the city. Although this is not the main focus of the exhibition, it is salutary to consider this long history of intolerance when we find ourselves once again – something we never expected to see again in our lifetimes – confronted with the baying of antisemitic mobs.

Luminous: A thousand years of Hebrew manuscripts

State Library of Victoria to April 1

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout