Meat matters at Berlinde de Bruyckere's We are All Flesh exhibition

THE title of Berlinde de Bruyckere's exhibition at Melbourne's Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, We are All Flesh, is deliberately ambiguous.

THE title of Berlinde de Bruyckere's exhibition at Melbourne's Australian Centre for Contemporary Art is ambiguous, and deliberately so. We are All Flesh can be understood as the assertion that we all have a fleshly, corporeal nature.

We may sense a theological note, an allusion to verbum caro factum est: the word was made flesh. Or it could be taken as meaning we are nothing but flesh, a reductive definition of the human as no more than a collection of physiological processes doomed to grow old, die and decay.

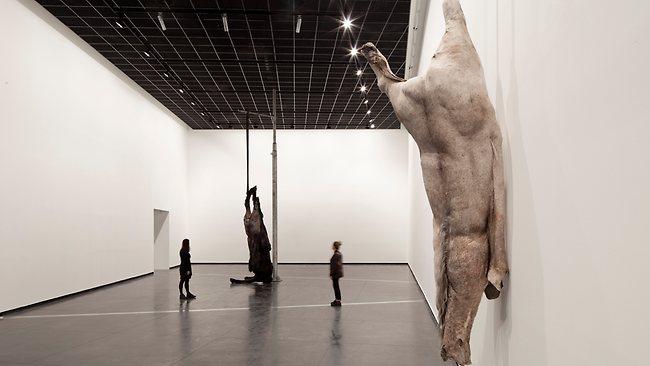

Entering the exhibition does not entirely dispel such questions but it focuses the mind on a very concrete form of corporeality. We find ourselves in a vast space filled with only two objects, but ones that other visitors were clearly finding somewhat disturbing. The first was what seemed to be the carcass of a horse, with head and extremities cut off and hanging like a slaughtered beast in a butcher's shop.

The subject - in painting at least - has a long history in art. Its most famous exponents have been Annibale Carracci, Rembrandt and Chaim Soutine. So we find ourselves immediately in the presence of an object that is at once disturbing yet can claim an authoritative art historical pedigree from baroque to modernism. But of course there are differences. Horses are noble creatures, even in countries such as de Bruyckere's Belgium, where they are eaten.

And then the animal, though headless, still has its skin, whereas the carcass in the butcher's shop is always flayed. The difference is analogous to the famous distinction that Kenneth Clark made between the naked and the nude, or the sort of cultural boundaries that Claude Levi-Strauss discusses between the raw and the cooked. In this case, the flayed carcass is no longer a dead animal, it is food. The animal with its skin on is still a dead animal; it is confronting in a different way.

Those who have purchased an animal from a traditional French market will have experienced the difference: hares, geese, even boars hang outside in the cold, in all their fur and feathers, as though just killed. You choose the animal, pay and come back later to pick it up skinned or plucked, cleaned and ready for the kitchen. Not an experience for some of our contemporaries who are too squeamish to bear the sight of a calf on a butcher's hook and will buy a pair of chops only if they are packaged under skin-tight plastic wrap, on a styrofoam tray with a sanitary pad underneath to soak up any organic leakage.

De Bruyckere's horse is thus disturbing first of all because it is a horse rather than a cow, and second because it is still clad in its skin rather than properly prepared for eating: so instead of evoking food, it hints at some act of cruelty or sinister ritual killing. Such changes of context can radically alter the meaning we read into appearances. In reality, though, it turns out to be the very opposite of the flayed butcher's carcass, for it is nothing but the hide, the bones and flesh cut out and replaced by wax and resin to maintain its form.

The other thing that is worrying about the horse, although it may not strike viewers at once, is its closeness to human anatomy. All mammals have a similar skeletal structure, only varying in the relative dimensions of various bones. Thus both the elephant and the giraffe have, like us, seven cervical vertebrae, only in the elephant they are comparatively flat and in the giraffe they are very elongated. One of the most significant differences is that in quadrupeds that need to run fast, such as the horse, metacarpal and metatarsal bones have evolved into what is effectively a third section of the leg.

The most obvious difference between humans and other mammals, especially quadrupeds, is our erect posture. Standing upright means the human arms rotate backwards, the scapulae move from the side of the body to the back, and the chest spreads and becomes broader rather than deeper. The effect of these changes, together with the extra section of the quadruped leg, which confuses our perception of its structure (how many people know where the horse's knee is?), is enough to mask the similarity between our corporeal structures.

But that similarity is revealed as soon as the animal's body is seen vertically rather than horizontally, and suspending a quadruped's carcass by a foreleg, simulating the effect of the erect stance, can make the analogy of our corporeal structures almost shockingly evident. That is in fact what we witness on entering the exhibition - we see not only a dead horse but forms that we recognise as a back, a chest, a pelvic girdle, and all under the alien covering of an animal hide.

Further into the room is an even stranger and more sinister object, which turns out to be two horses' hides stitched together so that one is upside down. The neck of the lower one hangs limply, hollow like an empty sleeve, perhaps the most unpleasant detail of all. Nearby, a helpful gallery assistant was explaining to a concerned visitor that the artist acquaints herself with the horses while they are still alive, though presumably already aged, then collects their hides after they have died of natural causes.

The next room reserves more surprises. First we encounter an installation of long stick-like objects resting on cushions and suspended in a cradling structure. What is disconcerting is that the objects we may take for sticks are in fact executed in wax in colours that emulate the appearance of flesh, and on closer inspection they seem to become even morphologically more like soft tissues at the upper end of the installation. Here, the point seems to be to suggest a continuity between the living tissues of the plant and animal worlds.

The following room has a series of antlers that have been given the same flesh-wax treatment, but these are the least convincing and the most repetitive of the works in the exhibition. In contrast, there is a strange object lurking at ground level, designed to surprise because, from the angle one approaches it, it seems to be an amorphous lump of wax resting on a sort of mattress.

On turning around the other side of this object, however, one discovers it is a human body, crouched and curled up like corpses found in ancient burials. The effect of surprise is increased by the extremely, even grimly, realistic nature of the body: while I was looking at the work, two French girls came in and one of them squealed in shock when she discovered the forms of a torso and leg behind what she too had taken for a shapeless mass.

The figure is strangely truncated, without arms or a head and consequently with an overly elongated torso. But the most striking thing about it is the colouring of the wax of which it is composed. Before you recognise it as a body, the pigmentation is less significant, but once this most familiar of forms gives the object an unmistakable meaning, we realise the wax has been coloured in livid pinks and greys that recall nothing so much as the discolouration of a cadaver beginning to decompose.

This scrawny, pathetic figure is not sleeping but dead; it is an image of a body no longer animated by life but overcome by the entropy of mortality, reclaimed by the order of the inanimate and returning to matter: earth to earth, dust to dust. In the history of art, the closest analogy is to the dead body of Christ, and one thinks particularly of Gruenewald's Isenheim altarpiece - today in its own museum in Colmar in Alsace - with the martyred body of the crucified Christ on one panel and the glorified body of the resurrection on another.

De Bruyckere belongs to the same tradition: the northern alternative to the classical tradition of antiquity revived in the Renaissance. The Greeks introduced the revolutionary idea that the body could be beautiful, instead of merely sexually attractive when young and fresh, unattractive when worn out, or in extreme cases actually repellent. The representation of the body as beautiful was not a fantasy of physical perfection but an idea about man: the harmonious image of the figure was a metaphor of the harmonious ideal of what we now call humanism.

The Christians never liked this idea, since although they believed God had originally made man's body perfect and beautiful at Creation, that body had since been polluted by sin and was now to be considered with suspicion. To the sexually repressed, naked figures were not joyful expressions of human potential but incitements to lust. The early Christians even condemned the care of the body, including the personal hygiene of the ancient world: cleanliness was not next to godliness but next to temptation. This is why Gruenewald's image is such a definitive expression of the northern Christian, anti-classical aesthetic: it clearly asserts the abject state of the body in this world, only consoled by the promise of a glorified body of light after the resurrection.

De Bruyckere comes from the same world, with the same abject and fallen view of the human body. The Christian note we detected at the outset was not misleading. I commented on a similar sensibility in the collection at the Museum of Old Art and New in Hobart - despite assertions by MONA's owner, David Walsh, about the paramount importance of sex and death, it was overwhelmingly death and decay, gloomily puritanical in their implicit condemnation of life, that were celebrated in his collection. If he doesn't already own a work by de Bruyckere, he should consider acquiring one.

But why this ultimately grim and and reductive vision? There is a long history in the modernist tradition of assuming the beautiful must be a lie and that ugliness must be evidence of truth. One can understand the origin of this idea in a reaction against ossified academic standards, and simultaneously a revulsion against the hypocrisy of society. The modern world has seen more systematic moral dishonesty than any previous age, from Victorian moralism to political propaganda of all sorts and the manipulations of contemporary commercial culture.

But it is nonetheless a fallacy, like the mistaken assumption that cynicism is more likely to be correct than good faith. We have to reflect that if optimism can sometimes be stupidity, pessimism can often be cowardice. Hope and aspiration, even idealism, can be powerful forces for understanding the world; beauty, when real and not illusory, can be the deepest manifestation of the real. Truth, above all, is profoundly complex, and is never found in the self-indulgence of nihilism.

Berlinde de Bruyckere: We are All Flesh

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, to July 29