Marion Mahony Griffin: the urban designer Australia forgot

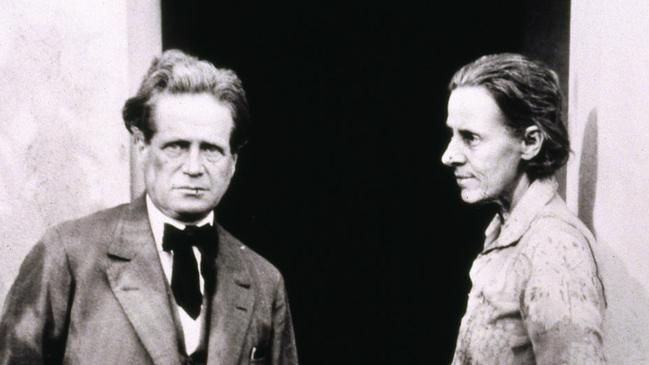

The Griffins were a formidable team who placed nature at the centre of their architectural creations but Marion Mahony Griffin was an extraordinary visionary

In 1914, Walter Burley Griffin and his wife and professional associate Marion Mahony Griffin came to Australia after winning an international competition for the design of the new capital of the Commonwealth. Both were inspired by the spiritual movement of anthroposophy, which entailed a profound feeling for the natural environment, but also, in their social thinking, by a fundamental belief in the value of democracy.

It is significant, then, that an exhibition devoted particularly to the work of Marion Mahony Griffin although inevitably including the couple’s joint work, should have opened on the same weekend that saw the painfully drawn-out conclusion of a presidential campaign that has strained American democracy almost to breaking point.

What the experience has reminded us is that democracy is not just about the rule of the people. It is essentially a system in which the people are consulted at regular intervals about the delegation of power to representatives who will conduct government; in the course of these consultations, or elections, the various candidates for these roles present their respective plans and policies and try to gain the approval of the electorate.

For this system to work, certain structures must be securely established, including stable political parties representing a range of responsible policies that are sufficiently different but do not venture beyond a range that is broadly acceptable to the whole community. And this, in turn, presupposes a still more indispensable condition — the rule of law.

The will of the majority can only be allowed to determine the outcome of an election because the rights of the minority are protected by law. Those who win in an election, in other words, cannot kill or imprison or rob those who lost. The will of the majority of the people is thus tightly circumscribed by something even more important — the rights of all the people. When law and the other institutions of civil society are not functioning properly, elections are simply ways for dictators to gain sham mandates.

Demagogues and populists, however, try to bypass these systems, which are designed to guarantee security, order and justice, appealing directly to social groups who feel impatient and disenfranchised. The opportunity for this arises, of course, when there are significant groups who have ended up being, or feeling, unrepresented through the normal system — as in America the old working class feels abandoned by conventional politicians.

There is clearly a fine line between appealing to a particular constituency or class within the conventions of the political system and encouraging a spirit of revolt or insurgency, and a sense of distrust in the political system itself. When that line is overstepped, the demagogue is in effect fostering a spirit of mob rule, and as we have seen again this year, mobs are essentially reactive: one mob generates another, antithetical mob, and rational discourse is replaced by anger and confrontation.

Mobs are inherently partisan, divisive and angry: populism fragments society into antagonistic tribes, fostering an introverted focus on difference that is corrosive of a broader sense of the body politic. For a democracy to function properly, all of its members need to see themselves as citizens first, not as belonging to fractional groups defined by colour, sex, ethnicity, religion, or any other criterion that they do not have in common.

Such principles were self-evident to people like the Griffins, formed particularly by the democratic theories of the American modernist architect Louis Sullivan. He was in turn the mentor of Frank Lloyd Wright, for whom Marion Mahony worked — draughting plans and beautiful presentation drawings in a distinctive style influenced by Japanese prints — before she met Walter Burley Griffin.

In these drawings, like one of the residences the Griffins had designed for themselves in 1911 but never built, she typically includes the floorplan lower down and above it an impression of the house as it is projected to look upon completion. The houses are often shown from a low angle, as though looking up a hill, but sometimes from above, in an imaginary aerial view. Most notable, however, is the way that she emphasises their situation in nature not only by surrounding them with trees and other natural features, but by placing trees prominently in the foreground, so that we seem to look through them to discover the house.

The original plan for Canberra represented an ambitious conception of architecture and city planning as establishing the framework for civil society. Some of its distinctive features are well-explained in a short video produced by the Walter Burley Griffin Society to mark its centenary in 2012 and posted on YouTube (search: Canberra the Griffin vision). But it was essentially a layout that sought to make the relations between the various parts of the social and political life of the city visible and intelligible.

It also stressed the priority of the citizenry of a society even over the government, by placing a symbolic Capitol structure on the hill today occupied by the federal parliament; the original site of Parliament House was to be lower down. Opposite, on the site now occupied by the War Memorial, was to have been a so-called Casino, by which was meant a kind of communal gathering place, not, of course, a den of gamblers and criminals.

Burley Griffin’s vision for Canberra soon fell foul of small-minded and penny-pinching bureaucrats, and the project ended in disillusion for him and his wife. Progress was also slowed and the availability of funds drastically affected by the two world wars and the Great Depression. It was not until some years after World War II that the building of Canberra was seriously resumed, and even then bureaucrats and committees tried to cut corners and save money by reducing the scale of the lake or even eliminating it altogether. Fortunately the project, central to any kind of grandeur in the city planning, was strongly supported by Sir Robert Menzies, who inaugurated it finally, with the name Lake Burley Griffin, in 1964.

Meanwhile the Griffins had moved on to another project, not the comprehensive design for a capital city to be built from scratch in empty fields, but a more modest conception for a suburban development on Sydney Harbour. And yet this project too was inspired by deeply held convictions not only about architecture, but about communal life and especially about the relation of domestic architecture and social life with the natural environment.

The new suburb of Castlecrag was planned and developed by the Griffins in the 1920s — in that short happy period of economic prosperity and optimism preceding the Great Depression — and it was designed from the beginning to be entirely different from the endless miles of Australian suburbia with its red-tiled roofs baking in treeless deserts. The approach was even further from the more recent horror of McMansions, occupying every allowable inch of their blocks, and bloated inside with multiple garages, oversized bed and family rooms and so on.

The houses actually designed and built by the Griffins were small and compact, with the flat roofs preferred by the Prairie School architects like Wright. They were made of stone quarried on the site, in a solid rustic construction animated by angular decorative motifs that sometimes evoke pre-Columbian cultures but today look like the formal language of art deco.

There were to be, in the words of a promotional booklet from 1928, “no unsightly fences, backyards or obstructions to the views”. There was thus open space between the houses, in which the natural rocks and trees were disturbed as little as possible. As the same booklet notes elsewhere: “All the recreation reserves form a single system and are connected by a network of pathways, passes and shaded lanes … An incalculable asset has been the segregation of four miles of water frontages common reserve to all the lot holders.”

Another resource worth looking up on YouTube is a contemporary promotional film, also from 1928, which has been restored by the National Film and Screen Archive (search: Castlecrag Sydney NFSA). This film, which also includes footage of Marion serving tea to friends as well as both Marion and Walter kayaking on the harbour, celebrates Castlecrag as a community of like-minded people — cultivated, creative and nature-loving — rambling through the network of pathways leading down to the water and enjoying the views of the harbour that open out in every direction.

Towards the end of the clip is footage of a dance or theatrical performance, and another of the innovations at Castlecrag was the open-air theatre built by the Griffins in the early 1930s, the Haven Scenic Theatre (now the Haven Amphitheatre).

The exhibition includes an immersive reconstruction of the experience of being in this natural performance space, but even more intriguing are photos outside, taken by an unknown contemporary photographer, of a production of Euripides’ Iphigenia Among the Taurians there in 1935.

Later productions have included Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1976), Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance (1989), Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra (1991), Handel’s Messiah, with the Willoughby Orchestra and Choir (1993), and Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood (1994). The theatre has unfortunately been closed for renovations for the last few years.

The Castlecrag development was inevitably affected by the Depression and then interrupted by Burley Griffin’s death in 1937 and Marion’s return to America soon afterwards, so that only 14 or 15 houses were completed under the couple’s direction. And the idea of a kind of development that put the natural environment first and tried to fit houses into it with the minimum of disruption remained for a long time foreign to the Australian psyche.

This is reflected in a good-humoured way in a comic map of Castlecrag drawn by Bernard Healing around 1973. In one little vignette, a father shows his children a man about to be executed by a firing squad: “He was caught cutting a tree down.” In another, a visitor points into the bush and says to his wife: “There’s a Griffin house there, dear, but you can’t see it.”

And yet while these ideas had become part of the currency of humorous reference to modern architecture and town planning, much of the ethos of building to connect with nature and respecting the existing environment as far as possible became natural to architects of Robin Boyd’s generation and widely accepted by a wealthier and more educated clientele in the 1960s and ’70s.

The exhibition includes a film that documents Marion’s life and work, with a special focus on Castlecrag — its history, architecture and environment — including interviews with current residents, some of whom have gone to great lengths to restore their Griffin houses (and most often discreetly extend them). By an amusing coincidence, almost everyone has had water leakage problems with the flat roofs; but they are all conscious of enjoying and being custodians of a unique piece of Australia’s architectural and urbanistic history.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout