Margaret Tucker’s painful memories, as she wrote them

The Indigenous activist/writer’s memoir was heavily edited before being released in 1977. Read an extract from the intact version just now published.

In this extract from her re-released memoir, Indigenous author Margaret Tucker describes a police arriving at her school, and changing her life. The intact memoir has been published by the National Library of Australia.

We went to school as usual, and I was thrilled because an older boy and I were the only ones that got a difficult sum right. (Our teacher) Mrs Hill praised us, and as I am not too brainy, it really meant a lot to me. Between morning and lunch break, we heard the unmistakeable sound of a motor car, a Ford. They were very rare at that particular time, out where we were anyway. While we seethed with curiosity (but) dared not move, one or two ventured to ask if they may leave the room for a few minutes, but they were not allowed. Our schoolmistress was called outside for a minute and she cautioned us not to move until she returned. Like clockwork, everyone (well, not everyone—mostly the boys) got on the desk and took a peep through the window. They relayed to us what was going on outside. A policeman and a young man who was the driver were talking to Mr Hill. Mrs Hill came in for a minute, but she did not take any notice of the boys, whom she had surely seen jumping down from the window.

She was very upset about something. She called (fellow students) Eric Briggs and Osley McGee and spoke to them quietly. They left the school through the back door; I cannot quite remember everything that went on, but then the policeman and Mr Hill came into the school. Our school Marm seemed to be in a heated argument with her husband. She was very distressed. After a long discussion it seemed that Mrs Hill was against what Mr Hill and the Policeman wanted.

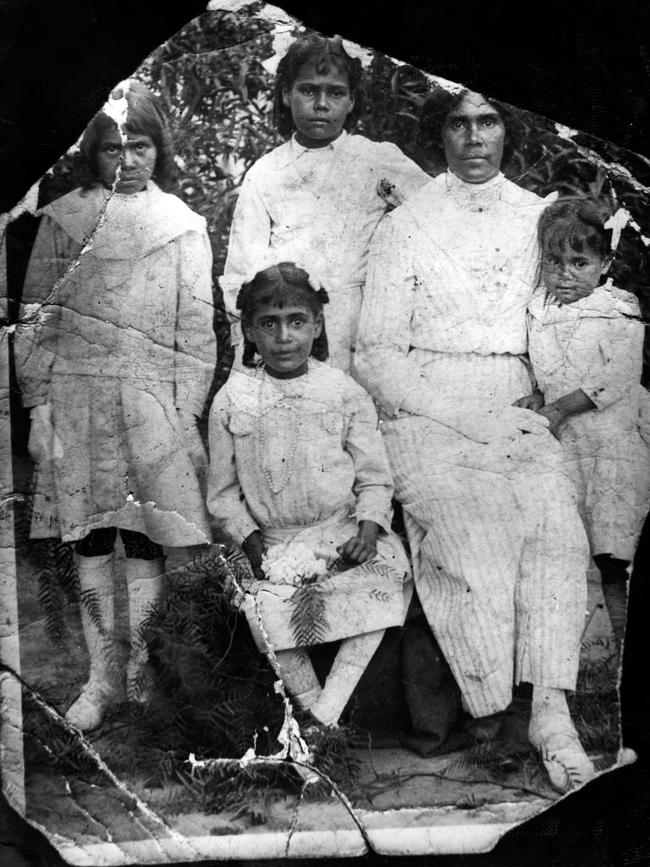

The children were all standing (we always stood up when visitors came and the police were no exception). My sister May and another girl, an orphan, started to cry. Then quite a few children started to cry. They may have heard the conversation. However, I was puzzled to know what they were crying for, until Mr Hill said that all the children should leave the school except Margaret and May Clements and Myrtle Taylor. Myrtle was an orphan reared by Mrs Maggie Briggs, she was the same age as May, about eleven years old and a very fair skinned, pretty child. Her aunt was Eric Brigg’s mother, a descendant of Trugginini.

I had forgotten about Brungle and the visit by the gang of men representing the Aboriginal protection board. Then it all came to me in a rush! But I did not believe for a moment that my mother would let us go. She would put a stop to us going away! All the children dismissed from school ran home and told their parents about what was happening at school.

I will never forget, when I looked out that school room door, every one of my Moonahcullah mothers, children and babies-in-arms, and a sprinkling of elderly men standing in groups. The younger ones were away working on homesteads, sheep stations, or farms. I started to cry when I saw them all through the schoolroom door. They were not allowed to come in. There were forty or fifty of my people silently or not-so-silently grieving and fighting for us. They did not know what it was all about; but they knew it was something treacherous to our Aboriginal way of living. Not being able to see ahead, we accepted the white person’s world to be a superior world. Around that particular part of Australia, I feel we Aborigines were fortunate in having a kindly lot of white station owners or squatters, homesteaders or what not. Our Aboriginal villagers did not worry them, of what I can remember.

There they were, all talking at once: some in the language, some in English, some with angry looks, and some with hopelessness, knowing that they wouldn’t have the last say. Some had tears running down their cheeks, the children’s cries mingling with theirs. Mr Hill demanded that we children leave immediately with the police. The Aboriginal women were very angry.

Mr Hill was in a situation he had never experienced before and he did not take into account that Aboriginal hearts could break with despair and helplessness, the same as any human. Mrs Hill, with tears running down her cheek, made one more valiant attempt to prolong our stay. I did not realise that she had sent our radicals, Eric Briggs and Osley McGee to race those miles to get my mother. I will never forget her for that. She stood her ground, this red-haired white woman, against her husband, the police and the driver of the car. She said with determination, “Well, they cannot go without something to eat. It is lunchtime”. We said, “Oh, no thank you Teacher. We are not hungry”.

“All the same, you children are not going that long journey (first to Deniliquin, then many more miles to Finley, where we would catch the train to Cootamundra) without food”, she insisted.

She went to her house at the side of the school, taking as along as she dared to prepare something for us to eat. Her husband, with his face going purple, looked at his watch every few minutes. At last she came in carrying a tray with glasses of milk and the kind of food we only got at Christmas time. It was most delicious looking, but we couldn’t eat it. We were not hungry. She coaxed us to drink the milk and eat something. However, I remember, Mr Hill could not stand it anymore. He said a lot of time was being wasted and that the police officer and driver wanted to leave. We started to cry again, as did most of our schoolmates. Then, like an angel, our mother and the two boys came through the schoolroom door. Little Myrtle’s aunty rushed in with a few other mothers.

Oh, the glad cry of joy. We thought, “Everything will be all right now. Mum won’t let us go”. Little Myrtle cuddled up to her aunty. We had our arms around our mother and refused to let go. She still had her apron on and must have run the whole one and a half miles. She arrived just in time, due to that lovely red-headed teacher. As we grasp our mother and hung on to her she said with determination, “They are my children and they are not going away with you”.

The policeman, who was no doubt doing his duty, patted his handcuffs, which were in a leather case on his belt. May and I thought it was a revolver.

“Mrs Clements”, he said, “I’ll have to use this if you do not let us take these children, now”.

Thinking the policeman would shoot Mother because she was making such a fuss, we screamed, “Oh, we’ll go with him Mum, we’ll go”. In my heart I cannot forget any detail. It stands out as though it were yesterday. I could not ever see kittens taken from their mother and drowned without remembering that scene, although it is just on sixty years ago.

However, the policeman must have had a heart, because he allowed my mother to come in the car with us three girls as far as Deniliquin. She had no money and only the clothes she had on. Then the policeman sprung another big shock.

He said we had to go to Deniliquin Hospital to pick up Geraldine, who was to be taken as well. The horror on my mother’s face and her heartbroken cry; I try to wipe it from my memory. All she could say was, “Oh no, not my baby. Please, let me have her. I will look after her”.

As that policeman walked up the hospital path to get my little sister, May and I sobbed quietly. Mother got out of the car and stood wailing with a hopeless look. Her tears had run dry, I guess. I thought to myself, I will gladly go, if they will only leave our little sister Geraldine with my mother.

“Mrs Clements, you can have your little girl. She left the hospital with her aunt and uncle early this morning”, said the policeman.

Mother simply took the policeman’s hand and kissed it, saying “Thank you, thank you”.

Then we were taken around to the police station, where the policeman no doubt had to report. Mother followed him, thinking she could beg once more for us, only to rush out when she heard the car start up. My last memory of her for many years was her waving pathetically, as we waved back. May and I were crying, “goodbye Mum, we’ll be all right, don’t cry - pray Mum”. But we were too far away for her to hear us.

About The Book

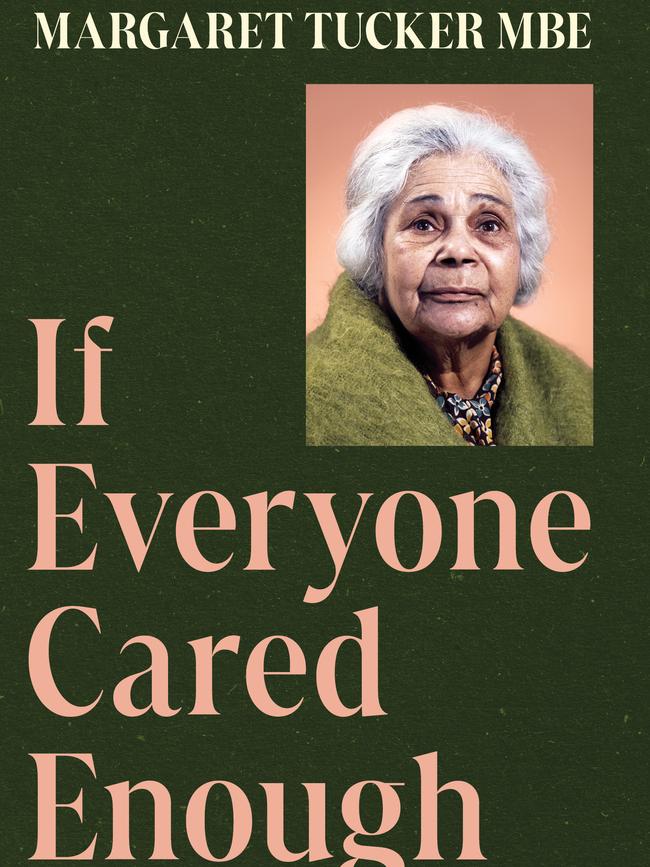

Margaret Lilardia Tucker was one of the first Aboriginal women to publish for mainstream audiences. Her landmark autobiography, If Everyone Cared, was first published in 1977, but the tone and content were modified, and her original Aboriginal storytelling voice was altered.

The book is now being republished by NLA Publishing, under the title If Everyone Cared Enough. The aim is to reinstate the original words of “Aunty Marge”, as she was affectionately known, including previously omitted descriptions of her culture and personal experiences. The new version draws from the handwritten manuscript held in the collections of the National Library of Australia, and will allow readers to experience Tucker’s story as she originally wrote it.

First Nations Peoples are advised that the book contains depictions and names of deceased people, and content that may be considered culturally sensitive. The themes covered may also cause distress, and language that is not considered appropriate today is used, reflecting the era in which the book was written.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout