Mao’s China: the cult revolution

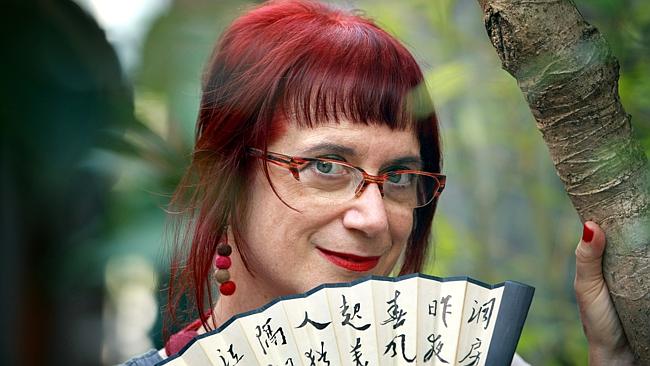

Linda Jaivin’s new book about China includes a chapter on the devotion encouraged by Mao.

The spring of 1967 saw the full flourishing of Mao’s personality cult. Larger-than-life statues of the Great Helmsman sprang up on campuses and in public squares. Every home and workplace acquired at least one Mao portrait, to which people bowed ritualistically in the morning to “ask for instructions” and again at night to ”report back”.

Young people performed flash-mob-style Loyalty Dances while singing adulatory songs with titles such as Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman, Beloved Chairman Mao, and If You Don’t Beat Them, They’ll Never be Overthrown. They compared themselves to sunflowers turning their faces to Mao, the Red Sun.

Billboards, banners and slogans proclaimed Mao’s wisdom on streets and farms and in schools and factories. Flight attendants led those privileged enough to fly in the recitation of quotations and singalongs on the journey.

“It is because our party and people have a helmsman of such genius as Comrade Mao Zedong and the great thought of Mao Zedong is the compass to chart the correct course through heavy fog,” the People’s Daily declared in a state of metaphorical overdrive, that “the great ship of our revolution has been able to steer clear of the countless dangerous shoals and hidden rocks and, in the teeth of great storms and waves, sail victoriously along the revolutionary course of Marxism Leninism.”

The propaganda machinery wheeled out a pantheon of model workers, peasants, cadres and soldiers, including Lei Feng, who shared the defining quality of a selfless devotion to Mao. There was even a model “internationalist” as well, the Canadian doctor Norman Bethune, who died of an infection in 1939 while serving with the Communist forces in the war of resistance against the Japanese occupation. Mao’s essay in memory of Bethune became a canonical text of the Cultural Revolution alongside “Serve the People”.

The Cultural Revolution produced a rich and colourful iconography, available as merch. Everyone wore at least one Mao badge. Some 2.5 billion Mao badges were produced in more than 20,000 designs over a 10-year-period. Some were as big as plates, others tiny, while some even glowed in the dark.

Thinking of the wasted metal, Mao is said to have remarked, “Give back our planes”.

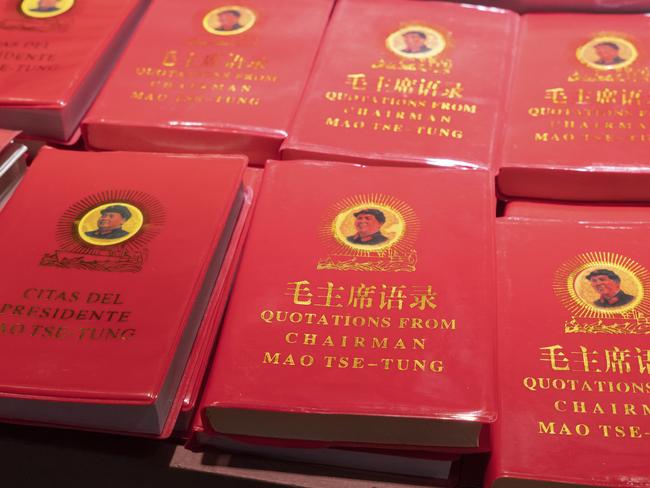

He might have asked for his forests back as well. In 1962, Mao’s writings comprised only 0.5 per cent of all published titles. By June 1966 they represented basically the whole Chinese publishing industry. By the end of 1967, China’s publishing houses had printed some 350 million copies of the Little Red Book (a state-subsidised bargain at RMB2) and 80 million copies of the then four-volume set of his selected work. These, along with his collected poems, a set of photographs and another of his publications were known as the “five precious gi’s”.

Royalties made Mao the richest person in China.

As traditionally was the case with Buddhist statuary or scripture, you didn’t “buy” Mao badges, posters, busts or books. You “invited” (qing) them into your home. (You still had to pay for them.) Accidentally defacing a newspaper that contained Mao’s words or photo was an act of heresy that could get a person imprisoned, a tough call at a time when his words and pictures were all over the press, and a lack of alternatives meant newspapers frequently did second service as rubbish wrappers, toilet paper, cigarette paper and even menstrual pads.

By the end of May, the arias from Jiang Qing’s revolutionary model operas, praised by the People’s Daily as “holding high the great red banner of Mao Zedong Thought”, could be heard everywhere. Any form of resistance had to be subtle to the point of imperceptibility and deniability. In Tibet, where the traditional sign of respect was to touch one’s head to a deity’s image, some slept with their feet facing Mao’s portrait.

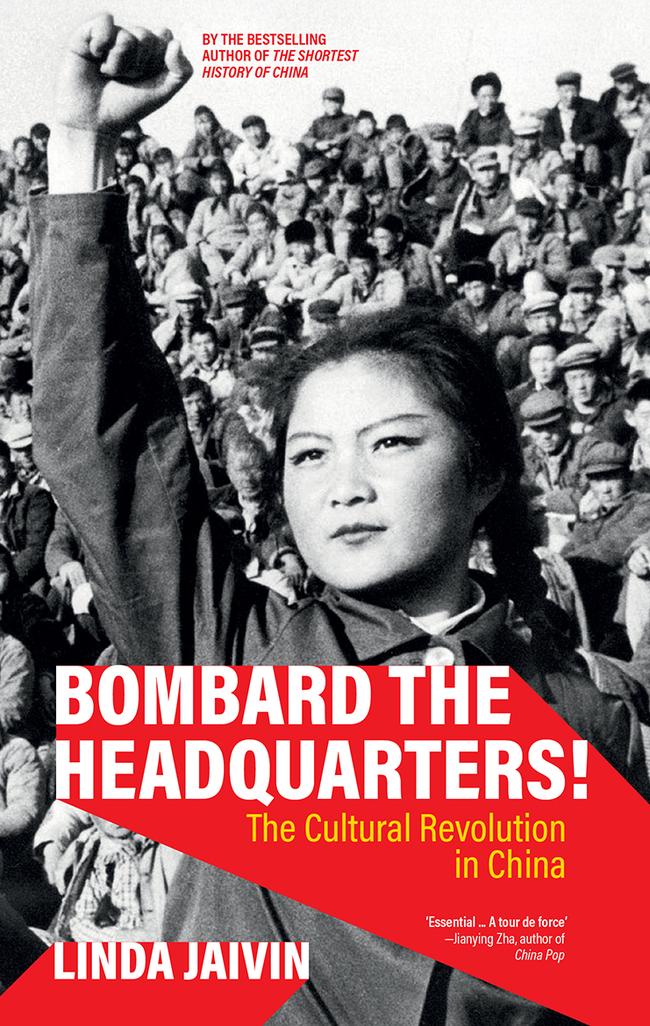

This is an edited extract from Bombard the Headquarters!: The Cultural Revolution in China (Black Inc) by Linda Jaivin, out next week.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Linda Jaivin has been studying Chinese politics, language and culture for more than 40 years. She has been a foreign correspondent in China, and is co-editor of the China Story Yearbook, an associate of the Australian Centre on China in the World at the Australian National University, and the author of 12 books, including The Shortest History of China.