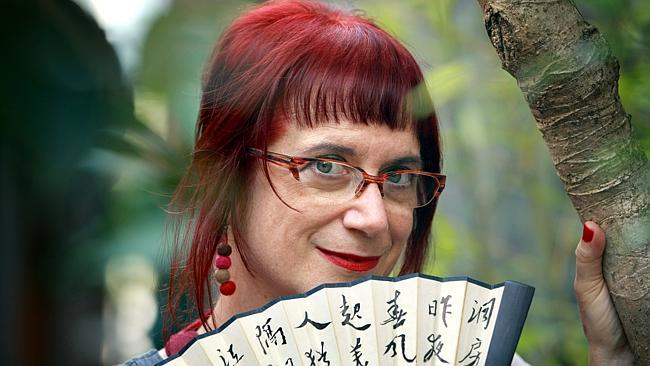

Linda Jaivin: the writer and her place in the Chinese puzzle

LINDA Jaivin’s latest novel is a supple and intricate piece of storytelling.

LINDA Jaivin’s latest novel is a supple and intricate piece of storytelling. While ostensibly a work of fiction (Jaivin’s seventh), The Empress Lover plays with the increasingly blurred lines between fiction, memoir and history. What results is a narrative that lays bare Jaivin’s relationship with China — personal, professional and imaginative — and how that relationship has forged the writer she is today.

In a small Beijing flat, Jia Peilin (Linnie) struggles to write the book that has haunted her for 25 years. A middle-aged Australian woman of uncertain origins, Linnie has a shelf weighed down by notebooks, each of them a failed attempt to write this “massive thing”. It’s the reason she’s returned to China — “it was a story that, I had realised, could never reach its conclusion unless I returned here to China where it began” — but still she scratches about for what it is she needs to say.

So Linnie keeps herself distracted. There’s Weibo (China’s answer to Facebook) and commissions to subtitle Chinese films. There’s her karaoke-singing landlady, Mrs Jin, who’s always popping by for a chat, and a lover, Q, who never seems to answer his phone. And then there’s the letter, delivered by a boy who looks like he’s stepped out of another century.

Freshly written, its ink still drying, the letter claims to have news of Linnie’s father. More important, it draws into the story of Linnie’s ancestry the (real life) British linguist and scholar Edmund Backhouse, whose somewhat discredited accounts of the court of the Empress Cixi were the inspiration for Linnie’s first novel, also called The Empress Lover, a “saga stuffed full of gratuitous, sensationalist sex scenes, murder, history lessons and purple prose”.

There is always something lively and mischievous about Jaivin’s writing, and early on, it seems The Empress Lover will be yet another of her erotic romps, the same sort of “ingenious pastiche” that Backhouse was renowned for. It’s a clever ruse, for when the meandering lines of this novel coalesce, it brings an emotional surge that’s as moving as it is unexpected.

Anyone who has read Jaivin’s 1995 debut novel Eat Me will know that she has a fondness for Mobius-like twistings and turnings that leave you never quite certain whether what you’re reading is real or imagined, truth or construct. Yet whereas in Eat Me the device had little other purpose than to give literary heft to an otherwise insubstantial story, here it underscores the often confusing and unpredictable layers of China’s political history, and how easy it is for individuals — whether native-born or otherwise — to get lost within them.

What Jaivin seems to be underlining is that this story — which encompasses China from its earliest dynasties to Tiananmen Square and beyond — cannot be told in one voice, nor can it be contained within the bounds of history or fiction. It requires an accretion of voices: Linnie, Backhouse, Backhouse’s doctor and a poet who once knew Q. Even Jaivin herself slips from novelist to historian, essayist to memoirist (her Chinese name is Jia Peilin).

One of Jaivin’s strengths as a writer is her delineation of the day to day of Chinese life, her astute insights into its culture and history. Here, her engagement with China is intensely personal, a love affair that — like Linnie’s affair with Q — endures, for all its disappointments: “Despite all that had happened, his history, our history, history’s history and the chasm that had opened up between us, I loved him still. My silly. My bad. My good.”

There are occasional moments where Jaivin loses control of the conjuring act that this novel is. Some shifts and coincidences are a little too improbable (even for a novel), and certain obfuscations seem more deceitful than clever. And much of the erotica seems out of place. Where in her 2009 novel A Most Immoral Woman she achieved a plausible balance between political and erotic elements, here her accounts of Backhouse’s amatory escapades threaten to upsetthe novel’s rather delicate equilibrium.

But for the most part, Jaivin gets it just right, with every word governed by Backhouse’s dictum: “Memory and imagination; the first counts as nothing without the second.” This is an elusive and enigmatic piece of writing, its fragmented narrative sifting through layers of Chinese politics and history, uncovering along the way the ghosts of the past that linger so persistently within the present. It’s a touching, inventive and gratifyingly unpredictable novel.

The Empress Lover

By Linda Jaivin

Fourth Estate, 318pp, $29.99

Diane Stubbings is a writer and critic.