Louvre affair reveals glory of Paris museum's art treasures

A NEW book that reproduces all the works of the historic Paris museum reminds us why great art stands out.

MASS tourism has had a drastic effect on the experience of art and art museums across the world during the past generation and more.

Museums you could once visit at leisure now have queues - or much longer queues - and even timed entry. On the other hand, buildings and collections have often been conserved, since they are now understood as assets, and in some cases more works are on display in galleries.

One museum that has had to cope, as almost no other, with vast and growing crowds is the Louvre in Paris.

In hindsight, the whole development of the Grand Louvre and the famous glass pyramid that caused such angst at the time was prescient, coinciding as it did with the great increase in tourist numbers of those and subsequent years.

There are still queues, and the vastness of the concourse under the pyramid is undoubtedly alienating, as are all utilitarian spaces where human beings are forced to swarm with their fellows, but the crowds are dispersed with relative efficiency into the three great entry points of the collection.

The Louvre is an enormous institution, not least because it covers the very different fields and categories of material that, in London, are more sensibly divided between the National Gallery and the British Museum. Pyramid or not, therefore, it is undeniably less pleasant and accessible than either of those relaxed, manageable and free institutions, while its holdings are so extraordinary that many visits are needed to do them any kind of justice.

The Louvre was not always such a big museum. It began as a medieval castle and was largely rebuilt in the 16th century under Francois I and Henri II. In the 17th century, the palace's connection with art and artists began when various painters and sculptors under royal protection were given studios there. Louis XIV's finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, had it renovated for the royal court, and this was when the magnificent eastern facade by Claude Perrault was built - after the king rejected an alternative proposal by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who had been brought to Paris for this purpose.

Louis, however, disliked Paris and chose instead to enlarge his father's old hunting lodge at Versailles as his home: what began as the extension of a residence turned into the building of a sprawling palace-city as the centre of the national government.

Abandoned as the principal royal residence, the Louvre was partly devoted to housing the royal art collection (largely brought from Fontainebleau in the early years of Louis's reign) and the Academie de Peinture et de Sculpture (1650-61 and then 1692-1793).

During the French Revolution, and following from earlier proposals, the National Assembly determined to turn the palace into a museum, whose initial holdings came from the royal collection and other works confiscated from churches and monasteries.

Under Napoleon, the collection was enormously enriched with plunder from the emperor's conquests, although the nation was obliged to give most of these things back after his defeat: the works restored to Spain alone, to give an idea of the scale, formed the basis of the Prado museum.

Many important works seized by Napoleon, however, were retained in the end. More acquisitions were made under the restoration and during the subsequent two centuries the collection has been greatly increased by purchase, but also by donation, benefaction and legacies.

The extent of the painting collection alone, covering the centuries from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the early 19th century, is clear from the size and considerable weight of The Louvre: All the Paintings, which consists of more than 780 pages, most of them with multiple plates.

As the title makes clear, the object of this book is to reproduce the whole of the painting collection, or at least the totality of the 3000 or so works exhibited in the galleries.

There is no doubt that having colour reproductions of every picture, even though many are not much bigger than large postage stamps, makes this an invaluable reference volume. Books that simply reproduce the most famous masterpieces of a period not only perpetuate a relatively simplistic view of art history but in fact make it harder to see those great works with fresh eyes because they are deprived of their proper context.

To see familiar works in the company of their contemporaries, on the other hand, and of other works by the same artist, helps us to appreciate their real originality: we understand what they were trying to do when we see what others were also attempting; and we appreciate what really makes them superior or unusual when we compare them with the average production of the age.

The book has four sections covering the Italian school, the northern schools, the French school and the Spanish school. All are well represented but the Italian school, with about 1000 works, represents the earliest focus of the collection from the Renaissance onwards, and reflects the central place of Italy in the history of early modern art.

The book as a whole has a preface by Henri Loyrette, director of the Louvre, and a general introduction as well as introductions to each school by Vincent Pomarede, head of the paintings department. These are, as we would expect, scholarly and informative, and especially useful as guides to the history of the acquisitions within each of these fields.

The same, unfortunately, cannot be said of the notices on individual artists and works of particular importance scattered through each section. These are the work of Anja Grebe, professor of art history at the University of Bamberg in Germany. It may seem odd that a French author was not engaged for this job, or rather different authors to cover each of the four schools.

Grebe's entries are mostly workmanlike but often uninspired and sometimes erroneous. Thus she writes about Botticelli, for example, without any reference to the crucial question of neo-Platonic philosophy, and makes no effort to explain why Mantegna might have assembled Mars, Venus and the Muses in his Parnassus. Her discussion of the Giorgione-Titian work Concert champetre is plodding and fails to acknowledge the picture's reference to bucolic poetry, which at precisely this point begins to play a role in the evolution of early modern landscape tradition.

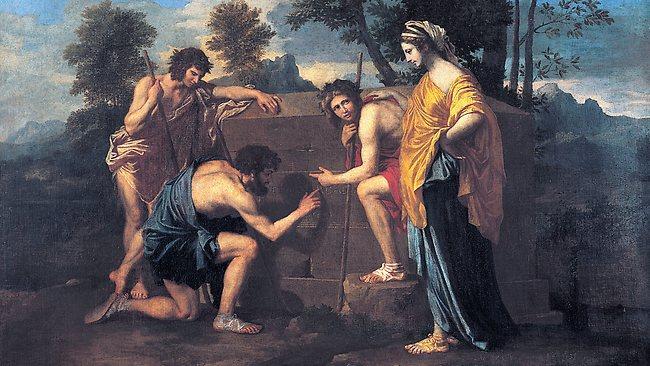

The French entries are particularly weak. Those on Poussin, for example - admittedly an artist who demands of the author learning and imagination - are generally unhelpful. There is no reflection on the particular significance Poussin attached to subjects such as the finding of Moses or his fondness for mythical figures who die and are transformed into flowers. Grebe thinks the female figure in Et in Arcadia Ego a personification of fate, when she is likelier to represent the Stoic idea of reason, and she gives a poor explanation of the arcadian theme in general.

In writing of Charles Le Brun, she calls him the director of the Academy of Painting and Sculpture, when in fact this was the only leading role there that he did not hold until very late, after Colbert's death. He was indeed the director by the time of Largilliere's famous portrait, but Grebe fails to see that the poignancy of this picture, with its recollections of Le Brun's great achievements, lies in the fact its subject was by now living through the greatest crisis of his career.

With Hyacinthe Rigaud's grandiose portrait of Louis XIV, there is no reference to its all-important context in the War of the Spanish Succession and no mention of the fact Philip V of Spain, for whom it was painted, was Louis's grandson (and ancestor of the present King of Spain) - let alone recognition of the subtle allusion to justice in the painted relief.

Grebe misunderstands the theme of departure in Watteau's Voyage a Cythere and also misses the pathos of David's Oath of the Horatii - namely that one of the weeping girls is a Horatia who is engaged to a Curiatius, one of their three opponents, and another is a Curiatius who is married to one of the Horatii brothers (David thus follows Corneille's expansion on the original narrative in Livy).

It is disconcerting to find that a reference book written by an art historian fails to give the reader vital information that, in this last case, is instantly available on Wikipedia, and with a little more trouble can eventually be found on the Louvre website as well. It makes one ask, in fact, what the purpose of a book such as this is in the age of computers and online reference resources.

The answer, despite all reservations, is that it can allow you to browse through a whole collection without having to search specifically for one thing or another, emulating the way we encounter works in the museum itself. This is why we have books and especially libraries: not just to look things up but to discover things we didn't know existed.

The Louvre: All the Paintings

By Erich Lessing and Vincent Pomarede

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 784pp, $89.99 (HB)

Christopher Allen is The Australian's national art critic.