London sketches outline Williams

The landscape master’s early drawings show he had a clear sense of direction, even if he didn’t know where the journey would lead.

It has never been easy for artists to find the true centre of their inspiration; generally it is only arrived at after a journey from some other point which in retrospect can be understood as peripheral. And how long that journey takes is contingent on many factors, including the character of the artist, the cultural environment, and perhaps particularly available opportunities for education and training.

It was a far more straightforward process in past centuries, when art was taught by apprenticeship, and when a young artist began by working in the style of his master. If he had any kind of original talent, that would express itself as a development from his initial style, so that there was an organic relation between his earlier and later work. If not, he could continue working as a professional practitioner of the second or third rank.

With the invention of printing and printmaking, which allowed paintings to be published as engravings from the high renaissance onwards, and with the rise of modern art schools and academies from the 17th century, the networks of influence became more complex, and the question arose in early modern art theory whether it was better for beginners to confine themselves to a single style or to attempt to draw on several models.

Even in the golden age of the 17th century, there was a vast difference between the experience of a Bernini, who was born the son of a sculptor and was producing masterpieces when barely out of his teens, and a Poussin, who was born in provincial France and took much longer to find his way to his true centre. It became progressively more difficult over the following centuries, as a loss of belief in shared stories was matched by a decline in demand for significant public commissions.

For the last century or so it has become harder again, with the crumbling of traditions, the failure of art teaching and the disorientation of art institutions. In the course of reviewing a large number of award applicants recently, it was clear that many had little ability and were deluding themselves that they could ever be serious artists; while at the same time they had received neither technical training nor aesthetic orientation from their time at art school.

It is interesting, in this perspective, to look at the outstanding exhibition of the early drawings made by Fred Williams during his time in London from 1952 to 1956, well before he developed the style, or even found the genre – landscape – in which he was to play an important role in the history of modern Australian painting and printmaking.

We can see at once that he is already on the journey to find what it is that he has to do, what he is able to do, what he has to say, in art. But none of this is obvious at first, and he naturally has no idea where that journey will take him. But one thing that is clear from this exhibition is that he knew the great masters of the past would help him in his quest: the whole exhibition is evidence of his avid attention to predecessors from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

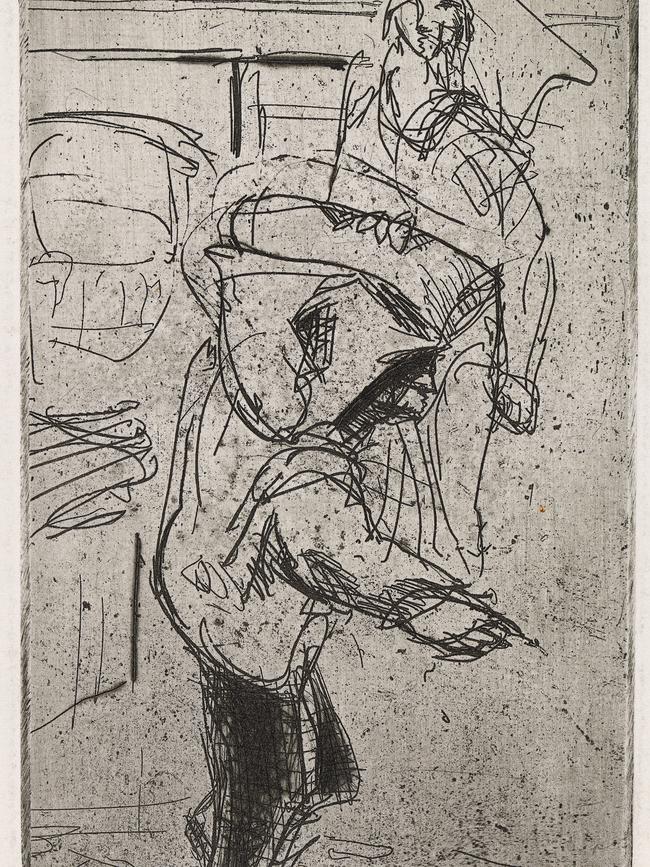

In London, he attended the Chelsea School of Art, and the first works in the exhibition are the life drawings he executed there. It is impossible to look at these without the benefit of hindsight, but it is worth trying to imagine what his teachers might have thought of them. One of the first things that may strike us is that Williams does not have a particularly strong grasp of anatomy; legs and torsos are frequently out of proportion. Nor is his style sensitive or responsive to the subtler aspects of the body.

On the other hand many if not most of the drawings demonstrate an instinctive feeling for movement: even if he does not understand all the parts of the figure in their correct relation to each other, he has a sense of how they function as a whole. This sense of the whole is sometimes overemphasised with heavy outlines, but it underpins the feeling for movement that will be crucial to his first mature work in printmaking.

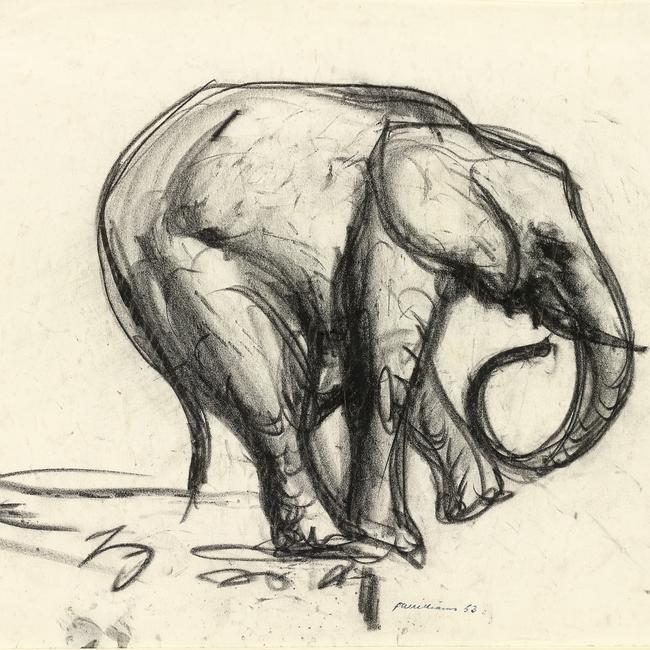

In the same way, his drawings of animals in the zoo, encouraged by Francis Lymburner, are largely studies in movement, sometimes lithe and rapid, sometimes loping and rhythmic, sometimes stolid, heavy and awkward. The movement of animal bodies is all the more interesting because mammals have essentially the same skeletal elements, differing mainly – if sometimes dramatically – in proportion. So their movements too are all like extrapolations of or variations on actions of which the human body is capable.

Some of the most memorable drawings in this series are of elephants, including one executed on a large scale and possibly intended for exhibition, in which the animal stands precariously on the edge of a ditch. There is more characterisation and a greater sense of pathos in these works, and one can’t help wondering whether Williams, himself a short and stout man, felt some special connection with the pachyderms.

The next series in the exhibition is of views of London, of houses, people and the countryside outside. In 1954, Williams did a course in etching, and this would prove an important medium for him throughout the remainder of his career. Two early etchings already show potential: one is of two men carrying a sheet of glass at the picture framer’s where he worked – he must have been struck by seeing the second man through the pane he was carrying – and the other is of a coal deliveryman with a heavy sack over his shoulder. Both prints display the sense of overall corporeal movement that was beginning to take shape in the life drawings.

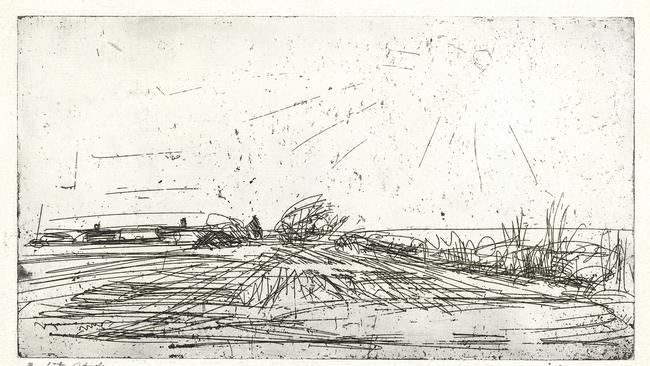

The other particularly notable works in this series are etchings of landscapes outside London, particularly West Wittering (1955-56) and Landscape with a Church (1955-56). Both are directly inspired by Rembrandt’s landscape etchings, but Williams’s intuitive understanding of the spirit of his models, of their structure, of the integration of natural and built elements, is vital and original. We also see him taking a cue from Rembrandt in embracing such aleatory effects of etching as foul biting, that will be so important in his mature prints.

These etchings, like Rembrandt’s, are strongly defined by the sense of the horizon and of the horizontal axis, and this is something that will remain with Williams in his mature landscapes too, perhaps unexpectedly. For although Williams does sometimes use the literal horizon in his landscape paintings and prints, he often dispenses with it, so that we seem to be looking straight into an unbounded view of the land without sky; and yet even here he tends to retain a very strong sense of both horizontal and vertical axes through the lines that represent the boundaries of paddocks, where undergrowth clusters around the fence-line.

The next series, although dating from the same years, is of music halls, particularly the Angel at Islington. As a form of popular entertainment, and as the wall labels point out, music hall had enjoyed its heyday from the late 19th century to the early 20th; it was probably already in decline between the wars, and by the 1950s it was certainly on its last legs.

But for Williams it had a meaning of which the mass of the audience would have been completely unaware: these rambunctious popular entertainments were a still living connection to the world of Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec and Walter Sickert.

It is Sickert who is particularly recalled in several drawings and prints of spectators looking down from their boxes, but the many studies of performers on stage and of his fellow spectators recall the work of his French predecessors as well. It is the contrast between these two groups that is particularly piquant, for him as for these earlier artists: on stage, performers creating a world of excitement and illusion; in the audience, ordinary people seeking a couple of hours’ respite from suffering, boredom and drudgery.

Williams was fascinated by the range of human types that surrounded him in the theatre, mostly of the popular classes, often seen in clusters, distinguished as much by their distinctive physical carriage and bearing as by their features; although one series is devoted to drawings in which he caricatures the double chins, the looks of surprise or the characteristic attitude of spectators’ heads.

It is the performers, however, who lend themselves to the most interesting development as subjects. Some are very simple and yet effective, like the trumpeter caught in a distinctive swaying as he hits a high note, represented both in a drawing and, slightly modified, in an etching. Other etchings are composed of a combination of drawings, like Vaudeville (1954-55), displayed beside the two drawings that were its sources.

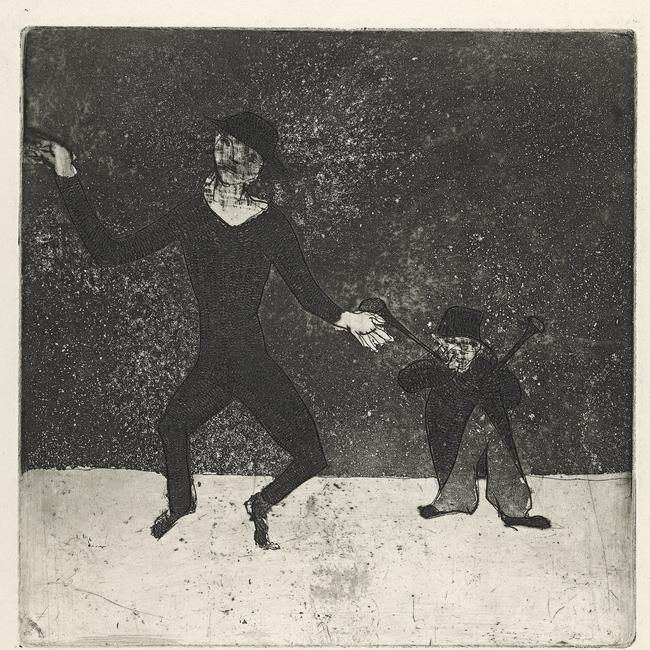

More integrated, and more technically accomplished, is another pair, Dancing Figures (1954-55) in which he uses both etching – very sparingly, to delineate figures and rudimentary features – and aquatint to create the dark areas of tone.

Here he is learning from the great example of Goya, but has not entirely mastered the technique: the background is too dark, too close to the black silhouettes of the figures, but he gets away with it because the performers’ feet are so expressively silhouetted against the brightly lit stage.

Williams had an imaginative affinity for this strange world of fancy and illusion – to which perhaps he, as much as his fellow audience members, needed to escape from the realities of work and daily life in London. And curiously the last significant artist to celebrate these whimsical and melancholy entertainments would be another Australian, George Baldessin.

Tumblers and acrobats, who have delighted and fascinated audiences since antiquity, were among the most magical of music-hall acts, and they are the subject of a couple of works in the exhibition which illustrate not only Williams’s maturing as an artist, but his increasingly clear sense of the difference between notations from life and the artifice of an image that is to speak to the imagination. Thus in a drawing of an acrobat at the Windmill Theatre, she is quickly sketched standing still at the start of a tumble, in her rather awkward circus costume, and in front he has noted in a few lines what she looks like in motion.

In the finished aquatint Acrobat (1955-56), however, perhaps thinking of the naked tableaux that were permitted at the Windmill – but only as long as the girl remained motionless – he has represented the performer naked, like a statue or vision. And, just as crucially, he shows her in the attitude of preparing for a handstand or somersault, yet fixed in stillness: forever charged in a state of potential dynamism and movement.

Fred Williams: London Drawings, National Gallery of Victoria, until January 29.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout