‘Literary miracle’ of Stalin’s pet plagiarist

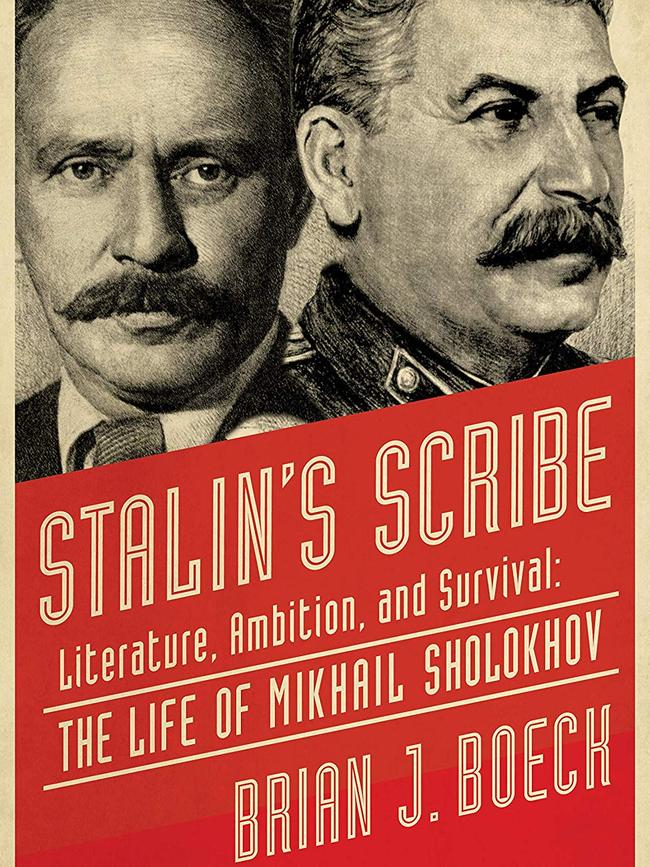

This is a fascinating biography of Mikhail Sholokhov, one of the most famous and controversial Soviet-era Russian writers.

Brian Boeck has written a fascinating literary and political biography of Mikhail Sholokhov (1905-1984), one of the most famous and controversial of Soviet-era Russian writers.

Boeck has a PhD in Russian history from Harvard and is the author of an earlier book, Imperial Boundaries: Cossack Communities and Empire Building in the Age of Peter the Great (2009), which set the scene for his deep interest in the Don Cossacks and Sholokhov’s celebrated four-volume epic novel, And Quiet Flows the Don.

That novel is about the love between a counter-revolutionary Cossack, Grigory Melekhov, and Aksinia Astakhova, during the Russian civil war (1918-20). It is described by Boeck as ‘‘the Soviet Union’s epic equivalent of Gone With the Wind’’.

His biography, Stalin’s Scribe, is about how the book came to be written, the career of its author and the politics of literature in Soviet Russia. Stunningly, Boeck writes at the outset that his book tells the story “ … of the brash young plagiarist who fabricated Stalin’s favourite novel and became one of the Soviet Union’s most prominent political figures …’’

These are carefully chosen, but hard-hitting words. It’s rare to see the author of a famous work accused of plagiarism. But here is how Boeck characterises the book’s composition, in 1926-27:

Between April of 1926 and September of 1927 Sholokhov performed a literary miracle. Never before — and never again — would a similar feat be accomplished. During those incredible months he managed to generate hundreds of typed pages of some of the most engaging prose ever to appear in Russia, a country blessed with Tolstoy, Chekhov, Dostoevsky and numerous other gifted writers … His literary output during those months exceeded the accomplishments of his whole career up to that point and most decades of his career afterward. The improvement in quality was incredible. None of his colleagues wept with rapture when they read his early, formulaic, communist short stories. Early editors sometimes had to apply a heavy, corrective hand just to get some of them into print. Suddenly, seasoned editors were in awe of his prose. Even more mind-boggling is the fact that this rapid, unexpected literary metamorphosis occurred at the age of 22.

The suspicion that plagiarism was involved in this ‘‘miracle’’ dates back to allegations first aired in the late 1920s, which dogged Sholokhov throughout his career. In 1965, a Russian critic, Vladimir Molozhavenko, “stumbled upon the story of Fedor Kryukov … a talented Don Cossack writer whom Gorky had praised for his penchant for truth. He was highly popular in the Don region before the revolution and was still remembered by older residents even though literary scholars had ignored him for decades. On the eve of the revolution Kryukov started working on a big novel devoted to the Cossacks. While suffering from typhoid fever during the ill-fated retreat of the White Armies in 1920, Kryukov would occasionally regain his senses and grab for a small metal trunk filled with manuscripts …’’

Sholokhov, Boeck argues, stumbled upon this metal trunk and found in it ‘‘an unfinished novel that ended around 1919 and a trove of scrapbooks consisting of stories, sketches, newspaper clippings and articles spanning over a decade of Cossack history … Applying imagination to restoration was just a first tentative step towards intellectual appropriation’’.

This makes Sholokhov into the mirror image of Mikhail Bulgakov, who died in 1940, and whose masterpiece, The Master and Margarita, was not published until 1966, but has made him among the most acclaimed Russian writers of the 20th century.

The suppression of writers such as Bulgakov is well covered by Vitaly Shentalinsky in Arrested Voices: Resurrecting the Disappeared Writers of the Soviet Regime. The dead were many. The life expectancy of creative artists who stayed on in Bolshevik Russia after 1917 was 45. For those who fled into exile in the West, it was 72. Sholokhov courted Stalin and lived to a lavish, drunken old age.

Boeck’s literary sleuthing has elements in it of Henry James’s The Aspern Papers, in which the anonymous narrator goes to Venice to try to acquire private love letters written by the famous but deceased American poet Jeffrey Aspern — a story inspired by the life of Percy Shelley and his love letters to Claire Clairmont.

Those letters are denied to the narrator by being burned. The dying Sholokhov burned the unfinished manuscript of a novel about World War II that Stalin had urged him to compose, but had been unable to write in 40 years. Boeck points out that this was redolent of Gogol burning the unfinished sequel to Dead Souls. But his hunt for the evidence has us in Henry James territory.

Rudiger Safranski’s recently translated Goethe: Life as a Work of Art (2017) is almost the perfect foil to Boeck’s life of Sholokhov. Marxist-Leninist literary critics, notably Gyorgy Lukacs, saw the polymath Goethe (1749-1832) as embodying the ideal type of the fully developed human being, but were never able satisfactorily to explain why this level of freedom and attainment became impossible under communism.

Whether we compare the range and vitality of his writing, or the free-spirited and untrammelled nature of his inquiries, or his relations with his political master, Duke Karl August of Weimar, the contrast between the life and work of Goethe and that of Sholokhov is extraordinary.

‘‘Vous êtes un homme,’’ Napoleon greeted Goethe, in a private audience at Erfurt, in 1808. Stalin’s demeanour towards Sholokhov, by contrast, was ‘‘Je suis l’homme’’ — and so much for the revolution. Reading Boeck is salutary, if only as a meditation on this rather sombre 20th-century theme.

Both the distinguished Russian editor and poet Aleksandr Tvardovsky and literary critic and editor Lidiia Chukovskaia denounced the ageing Sholokhov for a speech he gave in April 1966 in which he denounced Brezhnev-era dissidents. Boeck does not denounce Sholokhov, but he does show us a life trammelled and compromised by totalitarian politics and literary opportunism. He might have called it Sholokhov: Life in a Political Straitjacket.

Paul Monk’s books include The West in a Nutshell.

Stalin’s Scribe. Literature, Ambition and Survival: The Life of Mikhail Sholokhov

By Brian J. Boeck

Pegasus Books, 400pp, $46.95 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout