Lindy Lee exhibition at MCA melds the spiritual with the artistic

Taoism and Chan Buddhism are central to life and art for Lindy Lee whose works are akin to a meditation

Socrates famously observed, in Plato’s account of the speech he gave in his own defence, that the unexamined life was not worth living, or indeed not liveable. Part of the process of self-examination is to reflect on our own lives and experiences and on those of our parents, relatives and forebears; but part of it is also to ponder the much longer-term historical and cultural developments that have shaped our present environment as well as our character and personality.

Critical reflection of this sort is the only way to understand ourselves and our world, but it should not lead to neurotic self-absorption; on the contrary it should help us see our own lives and the history and traditions of our culture in a broader perspective, and to understand that many things we take for granted are habitual or conventional rather than natural. Ultimately it should help us to see beyond the bounds of personal ego and reductive collective identities.

The opposite of critical reflection of this kind, in fact, is unthinking identification with some idea of the self or ego. The unexamined self is both egoistic and tribal, because the tribe is just the ego extended to a group perceived to be the same as the self. Identity, unfortunately, is almost always implicitly defined as difference from people perceived as “other”, which the identifying group will despise if it is dominant or resent if it is dominated.

This is the trouble with the so-called identity politics that we see proliferating all around us, with the erosion of a strong sense of the body politic, whether conceived as the nation, the republic or the people. There has been an alarming rise in tribalism, polarisation and angry antagonism in the US in particular for years and this tendency — which feels like a collapse of the idea of an American people — appears to have accelerated in the year of COVID-19.

The picture is complicated by the fact members of the dominant group can align themselves with those they see as oppressed. This would be not be a bad thing if it simply meant standing up for them and seeking to right wrongs. But in the mood of our times, fuelled by the firestorms of hysterical opinion on social media, achieving real improvement is often forgotten in the race to express rage and guilt. And this is just another narcissistic pathology of the unexamined ego.

In Mon Coeur mis a nu, the collection of fragmentary writings by Charles Baudelaire published posthumously in 1887, there is an enigmatic entry under the title “Theory of true civilisation” that has stuck in my mind since I first read it decades ago. Translated, it reads: “It is neither in gas, nor in steam … it is in the diminution of the traces of original sin.” In many ways this note sums up the poet’s profound but deeply unconventional relation to the Catholic faith. But the essence of its meaning is that real progress is spiritual in nature.

In the same way, today, we might say that real progress in human civilisation ultimately entails the reduction of the pathological forms of the ego. Of course this is not to ignore the ecological crisis we face, with its many ramifications from economic equity to demographics. It is rather to reflect that greed of every kind, monstrous over-consumption and the unthinking destruction of the environment in which we and those who come after us have to live are grounded in unconscious and deluded habits of the egoistic mind.

Lindy Lee’s work, surveyed at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, represents a kind of evolution from the self to what lies beyond it. Beginning with early reflections on her cultural position as a contemporary artist in the Western tradition, she went on to think about her identity as an Australian born of Chinese parents and thus, like so many in a nation of immigrants, suspended between cultures. Finally she has come to focus increasingly, in her mature work, on what lies beyond the ego, although following a path suggested by her Chinese cultural heritage.

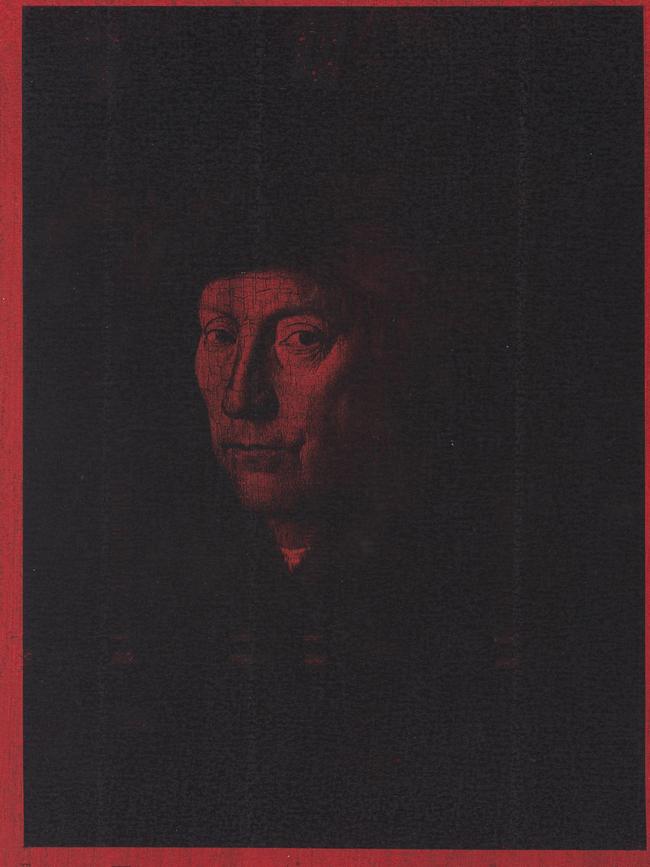

In Lee’s earliest work, she reflects on the great artists of the European tradition who had fascinated her, including van Eyck, Titian and Rembrandt. At the same time her sense of the remoteness or unattainability of these great images from the past was conveyed in photocopies of them veiled and partly obscured by thick brushstrokes of black paint.

In her next collection of work, she used photographs of her parents, her family and herself as a little girl as a documentary basis for pieces that dealt with the experience of migration to a new land, settling among people of another culture, and eventually growing up as an adopted member of that culture.

It was in the course of going back over her Chinese heritage, however, that Lee came to be drawn to the traditions of Taoism and Zen Buddhism, which have led to the mature work that occupies most of the present exhibition: within her Chinese identity, in other words, she found the way towards freedom from identification.

Chinese civilisation has two main belief systems, neither of which is exactly a religion, as well as Buddhism, which has a complex history in China and in its origins also was not a religion in the same way as other Indian beliefs, let alone the Abrahamic religions. Confucianism is a system of social duties above all, although it has implications for various other beliefs, such as the veneration of ancestors.

The other system is Taoism, founded by the semi-legendary Lao Tzu, who is said, like Confucius to have lived in the 6th century BC — that remarkable age for the human spirit in which Buddha in India and probably Zoroaster in Iran coincided with the origins of philosophy in Greece. Taoism is a spiritual system that teaches that all beings are connected and that we achieve things not when we act wilfully but in harmony with the ch’i or breath of life.

When Buddhism came to China from India, one current of the new teachings was deeply influenced by Taoism and became Chan Buddhism, which in Japan further evolved into Zen and had a profound influence on the character of Japanese civilisation, from the ethos of the samurai to the etiquette of the tea ceremony. It is a system of absolute presence, paradoxically finding efficacy of action in no-mind, very different from the tradition of Amida Buddhism, which is a religion of salvation.

For Lee, though, Taoism and Chan Buddhism have become central to her life and work. She practises meditation — the word Chan is the Chinese equivalent of the Sanskrit dhyana, which means sitting in meditation — and the sense of connection with universal being beyond time, space and personal identity pervades her work.

Her recent work takes two main forms, two-dimensional and three-dimensional. The first is what greets the visitor to the exhibition, with mysterious assemblages of flat bronze shapes, polished to golden brilliance and mounted on the wall of the gallery. These pieces are inspired by the Chan tradition of flung ink paintings and are made by pouring molten bronze on to a concrete floor; when cool, the successful pieces are polished to their present surface and assembled into collections of forms that are poised between chance and artistic conception.

Some of the intuitions implicit in these flat works are further developed in the three-dimensional ones, which were in fact a logical development, as Lee wondered how to pursue this theme in a three-dimensional way. Her inspiration here was also from Chinese culture and this time something deeply Taoist in spirit: the complex, naturally perforated and twisted rocks, generally limestone, known as Gongshi or scholars’ stones. Large ones are displayed in gardens, while small ones can be set on stands like sculptures and ceramics; they even appear as elements in ink landscape painting.

Lee first thought of making something like this by dropping molten bronze into water but was soon warned that this would be extremely dangerous because of the extraordinarily high temperature of the molten metal. In the end, her technical associates found a way to achieve her purpose by dropping molten tin, which melts at a far lower temperature, into a viscous mixture made of starch.

The result was small nugget-like objects that had forms and perforations very similar to the scholars’ stones. These small prototypes, some of which are displayed in a section of the exhibition, are then blown up to many times their original size using a kind of digital pointing machine according to a wall label, although in the video included in the show we see a craftsman apparently reproducing the complex forms by hand, carving a piece of soft styrofoam-like material.

This then serves as the model from which the bronze pieces are cast: the casting is done in sections, and these pieces then need to be assembled and the whole piece polished to the surface we see in the exhibition. The reason these objects end up being absorbing and meditative is that they embody two opposite forces: the randomness of violence that causes the molten metal to explode into these twisted forms, but also the force of cohesion — the mutual attraction of molecules that underlies the phenomenon of surface tension — that makes the exploded material hold together. They represent, in other words, both the tendency of the universe to dispersal and randomness, and its opposite tendency to unity and wholeness.

The central gallery of the MCA, occupied almost a year ago by Cornelia Parker’s suspended installation, is now again filled with a series of suspended objects, in a work designed especially for this exhibition. It is in effect a series of more or less round screens, perforated with round holes of different sizes, all hung in parallel planes from one end of the room to the other, and illuminated in a low blue light.

Here too there is a balance between the complexity of the forms and the simplicity achieved by hanging the screens parallel to each other; in any other arrangement the effect would be one of confusion and tension. The sense of stillness is enhanced by the suspension of the screens, which exposes them to movement and disturbance; for stillness is not evoked by things that cannot move.

If the flung bronze and scholar stones works are objects of meditation, this room emulates the meditative state, the inner stillness of the mind whose relentless clockwork has been suspended for a time. There has been something of a fashion for immersive installations for several years, no doubt reflecting the passivity of contemporary audiences; but perhaps this room will help some visitors discover for themselves the stillness of presence beyond the apparently relentless current of time.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout