Leo Schofield opens 1001 Remarkable Objects at the Powerhouse Museum

Leo Schofield has had an eight-decade relationship with the Powerhouse Museum as a visitor, trustee, donor, champion and critic – but his latest role is the most surprising.

Search the name Leo Schofield in the Powerhouse Museum database and you might start to think the world is not so much an oyster as a laundry bag. How many silk jackets, tailored shirts and skinny Armani ties does one man need?

Schofield has donated these and many other items to the Powerhouse over the years. They certainly represent a moment in fashion time – like the snazzy orange pants by Robert Burton, and the pairs of tasselled loafers – and also form a kind of sartorial portrait of Schofield as he was in the early 1980s. It was the era when he was both an advertising exec and a hugely entertaining and rather feared restaurant critic, but had not yet embarked on his third career as a festival director and, more recently, an exhibition curator.

What you won’t find in the museum catalogue, at least not in the public one, are the trenchant letters to the editor from one Leo Schofield, of Potts Point. He has fulminated, frequently, at plans to destroy his beloved Powerhouse and move its historic collections to a new tower building in Parramatta. In a 2018 letter he couldn’t hide his contempt as the “myopic state government persists with its risible plan to relocate this august institution from its historic location in the heart of Sydney to Parramatta, whose locals are agog with indifference at the prospect”.

The Powerhouse evidently arouses strong feelings in Schofield whose connections with the place go back decades and run deep. He’s been an enthusiastic visitor, donor, fundraiser, trustee, champion and, yes, critic. He joined the protest on the Powerhouse forecourt, wrote the letters and bent the ear of politicians, begging them not to dismantle the museum. A well-organised campaign has helped save Ultimo from oblivion, with the result that both Parramatta and Ultimo will have branches of the Powerhouse – total cost, some $1.5bn – although the battle continues to save key parts of the institution from the wrecking ball.

Against this ongoing uncertainty, Schofield has been brought back into the fold. In what has the optics of a strategic move by Powerhouse management, he has been appointed guest chairman of a “curatorium”, leading a team of curators and designers to organise possibly the largest exhibition yet staged at the museum. The show, called 1001 Remarkable Objects, promises exactly what it says on the tin, bringing out 1001 of the eccentric, wonderful, rare and gorgeous things from the 500,000 objects in the collection.

The exhibition is the subject of a lunchtime interview with Schofield at Fratelli Paradiso, an Italian restaurant close to his apartment in Potts Point, and which he uses as a kind of de facto dining room.

I arrive early and watch from the table as he comes through the door, the waiters cooing and making a fuss. Schofield is 88 and is walking slowly, having done his hip after a fall. He’s wearing an argyle jumper and purple-framed glasses, and his eyes crease into a smile as he eases himself into his seat.

“I have had a very long association with the Powerhouse Museum – I worked out that, on and off, I’ve had an association for 80 years,” he says. “I’m 88, and I was eight years of age when I was first taken there.”

The lunch order is being taken. Schofield wants to share a plate of fried calamari, then he’ll have the lamb. Two glasses of Sicilian grillo are brought to the table.

Schofield has taken evident pleasure in revisiting the Powerhouse and helping choose the 1001 objects. The bulk of the collection these days is held at Castle Hill in a huge storage facility, something like a cross between Aladdin’s cave and an Amazon warehouse, with 3km of corridors and shelves.

One of the truly remarkable objects he and the team have chosen is a mousetrap-making machine from the Supreme Mouse Trap factory in Mascot – a glorious contraption of wires, gears and belts designed and built by Arnold Wesley Standfield. Schofield wants to pair it in the show with a Meissen portrait bust of Baron Schmiedel, court jester to Augustus III of Poland and Saxony. The baron has a mouse dangling from his mouth, its tail a thin thread of porcelain.

“No one quite knows, but the assumption is that it’s a satirical bust, designed to reflect the quirkiness of this jester who had an aversion to mice,” Schofield says. “There are only four known versions of this bust – it’s difficult to say how immeasurably rare they are. And there it is, turning up in Pyrmont.”

This is classic Schofield, cheerfully mixing high culture and low, Meissen and mousetraps, and wrapping it up in an alluring package. He’s not embarrassed to make the highbrow popular, or to celebrate the folksy and vernacular. He was, after all, the creative director who, for a TV commercial, had corks of cheap sparkling wine popping to the sound of Handel’s Royal Fireworks Music. And it’s an attitude that has underscored his approach to the Powerhouse exhibition. Even the title, 1001 Remarkable Objects, hints at the promise of magic and surprise, a bit of ta-da!

“We have been determinedly popular – not populist,” he says, spearing a piece of calamari.

“We want people to be curious, to investigate, to be drawn to different elements of the collection. We want, ‘Hey mum, look over here!’ Let’s have a good look at things.”

Schofield’s passion for collecting began when he and his former wife, Anne Schofield, were newlyweds living in London, in the early 1960s. They’d visit the great museums such as the Victoria & Albert, catch the Green Line bus to stately homes in the counties and browse the bric-a-brac on Portobello Road.

“It was an adventure and a revelation to see so much wonderful stuff in high states of repair and beautifully presented,” he says. “It was also a time when it was possible to go to Portobello Road and buy a couture dress – not that they had my size. But we went a lot to Covent Garden and Anne wore a lot of vintage. All the kids were running around London dressed in ancient threads.”

By the time they moved back to Australia in 1965, they had no money but had built up a virtual costume department of vintage gowns, gloves and shoes, dating from around 1750 to the Second World War.

The Schofield collection was shown at the 1974 Adelaide Festival and then was acquired, with a special government grant, by the National Gallery of Victoria.

“They took the lot,” Schofield says, explaining that it was a paid acquisition, not a donation. “Listen, this is a deposit on a house. Anne and I decided that we would sell it. We were offered the princely sum of $70,000, which would be the price of one Fortuny dress now. There were hundreds of items – hats, fans, shoes, stockings. It’s the core of the (NGV) costume collection, wonderful things that will never come on the market again.”

Schofield is telling this story – “A bit more vino? I think we might” – by way of saying that no museum in NSW at the time was interested in taking the costumes.

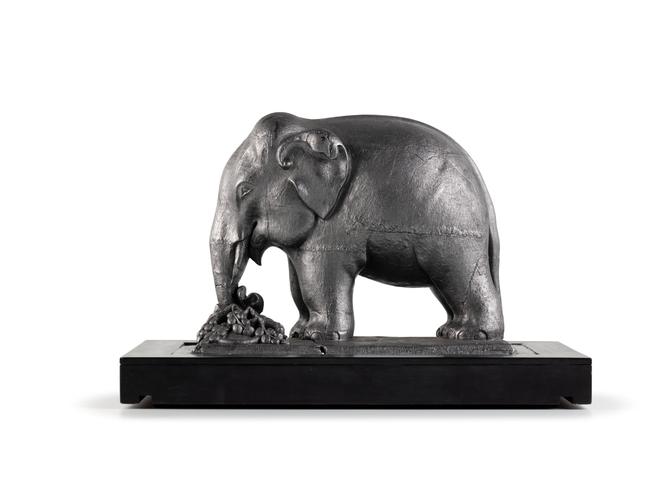

The Powerhouse, or the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences as it was then called, was a kind of “accidental” museum. Its origins were in the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879, a vast display of innovations in commerce, industry, the arts and sciences. It was staged in a temporary exhibition hall, the Garden Palace, whose magnificent dome and vaulted roof were built entirely of timber. It burned to the ground in a fire in September 1882. One of the few surviving exhibits was an elephant sculpture from Ceylon, carved in graphite – a seemingly indestructible specimen that will have pride of place in 1001 Remarkable Objects.

The Powerhouse began as the Technological, Industrial, and Sanitary Museum, originally housed in a shed with the Sydney Hospital morgue. It entered its own purpose-built premises as the Technological Museum in 1893, in Harris Street, Ultimo. Over the years it became a catch-all for seemingly anything that wasn’t strictly fine art or natural history. It could accommodate, for example, the extremely rare Boulton and Watt steam engine, from 1785, as well as trade samples, botanical drawings, ethnic artefacts, musical instruments, furniture and decorative objects. As the collection grew, much of it ended up in the attic or stored in a former wool warehouse in nearby Alexandria.

“The floors were thick with lanolin,” Schofield says of the warehouse. “There was no attempt at cataloguing. We just opened these boxes and went, ‘Wow’. The main thing was to get (the collection) out quickly, before someone lit a cigarette.”

By the 1970s Schofield was a well-known figure in Sydney. He was the creative director at the Leo Burnett advertising agency and had a second job as the nation’s “public stomach”. His first restaurant review, incidentally, was for The Sunday Australian in May 1971: “Café Florentino … where the French cutlets are Anglaise”.

Neville Wran, then premier of NSW, made him a trustee of the Powerhouse in 1979, just as moves were being made to give the museum a bigger and more suitable home. The plan was to shift the collection a couple of blocks along Harris Street, to the site of a former power station and tram depot, with the addition of a new building.

Wran was no longer premier when the Powerhouse Museum opened in 1988 but the new wing was named after him. Designed by Lionel Glendinning, its distinctive vaulted roof is a postmodern echo of Victorian-era structures such as the old Garden Palace. It remains, for now, one of the cultural legacies in Sydney of the 1988 Bicentenary, along with the Australian Bicentennial Wing at the Art Gallery of NSW.

“One thought, incorrectly at the time, that it really was a schizophrenic museum: half bells and whistles, and transport and machinery; and the other half incredibly good design objects and social history,” Schofield says. “But I have certainly come to the view that accidental though (the Powerhouse) may be, it creates a unique conjunction of objects.”

The museum brought together the historic and modern, industrial and decorative, rare and commonplace in a way that somehow made sense – from the famous Catalina flying boat to a reconstructed art deco cinema and working steam engines.

Then, across the past 15 years or so, the Powerhouse steadily lost its vroom. Exhibits became tired-looking and fell into disrepair. Curatorial departments atrophied, managers came and went, and exhibition space was given over to showbiz-themed attractions. Visitor numbers plummeted. There seemed no interest from government in reinvesting in the venue and keeping its exhibitions fresh.

In 2015, premier Mike Baird delivered the coup de grace, announcing that the Powerhouse would be moved from its historic location in Ultimo to a new building in Parramatta. Several premiers, parliamentary inquiries and policy backflips later, Ultimo will be retained and refreshed with a $500m investment – but the 1988 Wran building will be demolished to make way for a new annexe with a library, exhibition spaces, a roof garden and accommodation for school sleep-overs.

The Powerhouse Museum Alliance has rejected the “wasteful and unnecessary” destruction of museum infrastructure after just 35 years, but there may be a reprieve: the newly elected Minns government is reviewing the extent and cost of the project, and it’s possible the Wran building could be saved. Still, if the upgrade works go ahead next year, in full or in part, it’s likely that 1001 Remarkable Objects will be the last major exhibition at the Powerhouse until at least 2026.

Why would Schofield, such a vigorous critic of the Powerhouse in recent years, be drawn into staging an exhibition there? He says he took some time to respond when Lisa Havilah, chief executive of the Powerhouse, called to ask if he’d be involved.

“It was, I suppose, a moral position,” he says. “I’d gone on bended knee, begging Baird not to pursue that idea of bifurcating the collections. At that time, it was pretty clear to most people that (removing the Powerhouse from Ultimo) was a developer-driven idea.

“But as it’s panned out – which is the only thing that history does for you, irons out wrinkles – I agreed to take it on, provided I could work with people I have worked with in the real world, away from museology.”

Havilah says she invited Scofield to come up with an exhibition concept, and the result is “fully Leo”.

“He has such a long history with the museum,” she says. “It was an incredible opportunity to work with someone who knows the collection, but who would think differently about how to present it, and how objects fit together to tell new stories ...

“This exhibition goes wholly into the heart of the Powerhouse collection and how it has developed across 140 years.”

Of Schofield’s recent battles with the institution she adds: “You would never die wondering what Leo was thinking. That’s what I love about him.”

At lunch, Schofield takes a different tack. He says he and Anne – whose spectacular jewellery collection also is included in the exhibition – have decided to keep out of the politics of the Powerhouse and to focus instead on the museum they love.

“We support the institution, not individuals,” he says.

“I’m not interested in internal politics, I’m interested in doing the best we can with what we have available. We’re here to put on a show.”

Spread across 25 rooms, 1001 Remarkable Objects is said to be the largest exhibition ever mounted by the Powerhouse. Schofield’s team of exhibition planners includes art and antiques expert Ronan Sulich, marketing specialist Mark Sutcliffe and Powerhouse curator Eva Czernis-Ryl. Theatre designers Damien Cooper, Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace promise to give it all a ravishing display.

“What’s for pudding?” Schofield asks.

We order a very gooey lemon meringue pie and creamed rice, and share spoonfuls of each.

He has taken evident pleasure in selecting the 1001 objects and arranging them in ways that prompt a tangential thought or amusing juxtaposition – such as a preserved Arnott’s biscuit and a red-and-pink confection by fashion designers Romance Was Born.

“It’s inspired by the Iced VoVo,” he says of the outfit. “It’s two panels of pink with a panel of raspberry jam down the middle. Matching shoes and pompoms.

“At the same time there’s also one very large biscuit, which is the first biscuit baked by the Arnott’s factory in Newcastle. It came with the Arnott’s archive. There’s no reason not to put all that together. It’s asking people to think about things in a different sort of way.”

Schofield is not showing his old dinner suits and shoes, but some fine decorated fans that he donated to the Powerhouse are in the exhibition. A stunning intaglio necklace, made from gold, agate, amethyst, bloodstone, carnelian, garnet, lapis lazuli and onyx, and set in England around 1870, is from Anne Schofield’s recent gift to the Powerhouse. A pair of Tibetan gilt bronzes, of Brahma and Chandra, were donated in the 1920s by society figure and philanthropist Dame Eadith Walker.

“She had a beautiful house on the Parramatta River called Yaralla,” Schofield says. “She left all her fortune to the returned servicemen. She was one of the grand ladies, visiting royalty at court. There was a few of them around Sydney.”

Cups of espresso are brought to the table as lunch comes to an end, but Schofield could go on and on.

There’s an electric car, made by Anderson Electric Car Company of Detroit, in 1917 – well before Tesla was a twinkle in Elon Musk’s eye – and a marvel of modern Australian design, Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge. And what about the Coolgardie meat safe in the form of an obelisk?

“It’s ancient Egypt reincarnated in the west,” Schofield says with a laugh, his sales pitch undimmed.

And why would he not be excited about a show that’s all about social history, astonishing stories, beautiful things, and marvels of ingenuity? You couldn’t keep him away.

1001 Remarkable Objects is at the Powerhouse, Ultimo until December

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout