Kate Grenville’s A Room Made of Leaves is historical fiction at first blush ...

Kate Grenville feels in a playful mood with the ‘grey areas’ of the historical record, particularly when it comes to her latest novel.

First impressions count in Kate Grenville’s new novel, A Room Made of Leaves. Whether the impressions are fleeting or enduring, honest or “a second or third cousin to the truth”, is another matter. We might think of Donald Rumsfeld’s known unknowns, except we need to go back further than that, to colonial NSW under its founding governor, Arthur Phillip.

And when it comes to who is telling the truth, it’s not Phillip or any of his colonial co-lords we need to consider, but instead Elizabeth Macarthur (1766-1850), wife of army officer turned wool baron John Macarthur. To be fair, Mrs Macarthur is upfront about this. The epigraph to the novel is a quote from her: Do not believe too quickly! That “second or third cousin to the truth” is also from her, and it’s a bit of a confession. As is this final judgment of Macarthur: “Thank God I outlived him.”

The quotes are attributed to her, yes, but via Grenville. This is a novel masquerading as a memoir. It opens with an editor’s note explaining that during a renovation of Elizabeth Farm, the former Macarthur family estate near Parramatta, west of Sydney, a tin box was found in the roof cavity. Inside were Elizabeth Macarthur’s long-hidden memoirs.

Faded ink made the papers difficult to read, so the editor made “an educated guess at the words” and arranged the memoir “in a plausible order”. Beyond that, the editor has let the memoirist “tell her story in her own words”.

The editor is Kate Grenville and what follows, the memoir, is her novel, her first in a decade. It’s a powerful, humorous, historical recasting that will, in this reader’s view, be in the running for the 2021 Miles Franklin.

For the record, the real Elizabeth Macarthur did not, as far as anyone knows, write a memoir, as Grenville spells out in her afterword: ‘‘No, there was no box of secrets found in the roof of Elizabeth Farm. I didn’t transcribe and edit what you’ve just read. I wrote it.’’

The author, who has had a few run-ins with historians in the past, laughs at her cheekiness — her word not Mrs Macarthur’s — at mucking around with the “grey areas” of the historical record and “the whole notion of what a novel is”.

“I was always the naughty girl at school and clearly, even at my great age, I am still the naughty girl.’’

We are talking via Zoom, which means I can see when Grenville, 69, laughs, and she does so a lot. She is at home in inner Melbourne, where she has lived for the past three years. Her two children are now in their early 30s.

When I say I think A Room Made of Leaves is her funniest novel, she says she’s glad “because some of its subjects are serious”. She mentions her 1994 novel, Dark Places, a companion to her 1985 debut novel, Lilian’s Story, and its focus on child sexual abuse. She thinks Dark Places is one of her funnier books because it “gets under people’s radar”.

“A lot of people are not going to read the book, or will read it at a rather solemn level, guarding themselves. But if you can make them laugh, you have opened a door into their unguarded selves.’’

With her new novel, “I didn’t sit down and think, ‘I’ll write an amusing book’, but once you start sending up the whole idea of myths, heroic myths, surrounding people of the past, the way is opened to be kind or playful, or even a bit rule-breaking’’.

A Room Made of Leaves is the fourth book in a series set in old NSW. Grenville’s most celebrated novel, The Secret River (2005), short-listed for the Booker Prize, is set in the early 1800s and was inspired by one of the author’s convict ancestors. Sarah Thornhill (2011) is a sequel. The Lieutenant (2008), broadly based on First Fleet officer William Dawes, though in the novel he’s called Daniel Rooke, is set about 30 years earlier.

The new novel is contemporaneous with The Lieutenant and Dawes, named this time, is an important character. What this “tall, awkwardly-put-together man” and Mrs Macarthur do together is not in any history books, or any memoirs, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, according to Grenville.

“I’ve never claimed to write anything but fiction. I have never, ever called myself a writer of history,’’ she says. “I think one of the problems I have is that I begin my books by doing a lot of research in primary sources — because essentially the reality is always so much more interesting that anything you make up.

“So I go back to the primary sources and I think that is sometimes confusing for people because, necessarily, with historical fiction there is always this grey area, like a Venn diagram. There’s the stuff that has come out of the historical record, which is sometimes factual, and there’s the stuff that is completely fictional.’’

Grenville says she therefore understands why some people don’t like historical fiction. Interestingly, she adds that she doesn’t read much of it herself.

“I find that overlap, that ambiguity, that grey area, not the kind of reading experience I want. I’d much rather read history, actually, or fiction.’’ But she writes historical fiction and the first word in that generic label leaves her open to “You-don’t-know-thats”. She sees a kinship with Hilary Mantel and her Wolf Hall novels set in Tudor England.

“When you are putting dialogue into the mouth of Thomas Cromwell, for example, it’s a very cheeky thing to do.

“I’m sure Hilary Mantel would not set herself up as a historian, any more than I do. But we’ve started it with our feet in the same place, with incredibly interesting, always enigmatic, historical figures.”

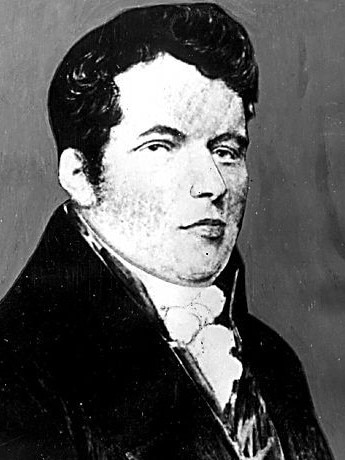

So let’s return to Grenville’s enigmatic figure: who we first meet as Elizabeth Veale, a farmer’s daughter in Devon. Here’s her first impression of then ensign John Macarthur:

Mr Macarthur was an ugly cold sort of fellow. There was nothing smiling or pleasant about him. A sullen bottom lip gave him the look of a petulant child, and he was badly marked by the smallpox. His eyes looked not quite right, as if they’d been put in carelessly, too far apart and one higher than the other. He was haughty, too, glancing around with his curled lip …

She married him in October 1788, drawn, she admits to the “banked fire’’ in him. “It was nasty and a nasty streak in myself responded to it.”

Seven months later Macarthur joined the New South Wales Corps and set sail for the colony. “I thought he was joking …” Mrs Macarthur says in her memoir. He was not, so she went with him, of course, along with their young son, Edward. Yes, her response to Macarthur started a little earlier than their wedding night. They would have seven more children. The landed at Sydney Cove on June 28, 1790, the colony just two years old.

Here are Mrs Macarthur’s first impressions of her new home:

Sydney Town was a dusty ugly angry place, a sad blighted bit of ground on which too many souls tramped out their days dreaming of somewhere else.

That is not what she wrote in her letters to family in England. She was a regular correspondent, and when Grenville quotes from a letter she does so faithfully. But in her editor’s note she marks this correspondence as the “bland documents” designed to represent Mrs Macarthur’s “public face”.

Indeed, she sees these letters, which praised the colony and the men who ran it, as semi-fictional or, to quote her protagonist, as “sunny embellishments”. In contrast, the private papers, the basis of the memoir that is the novel, are “a series of hot outpourings … with shocking frankness” that “invite us to see right into her heart”. They, of course, are made up but, as Grenville says, their invention doesn’t automatically make them untrue.

Grenville first became interested in Elizabeth Macarthur while she was researching The Secret River and read from her letters. “That means I have been thinking about this book for 20 years.’’ She also drew on Michelle Scott Tucker’s award-winning 2018 book, Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World.

She thinks Macarthur was an “extraordinary woman” who not only put up with “one of the most unpleasant people in Australian history” but managed his huge business during his long periods back in England. She was, in the author’s playful musing, “the mother of the Australian wool industry’’.

“I didn’t put anything in the book that was impossible of the historical record. Yes, we have to take what she says with a pinch of salt, yet I think I have created someone who is plausible and consistent with the historical record.’’

Grenville doesn’t want her novel to be branded a #MeToo book, but agrees she has, from her first book, the 1984 short fiction collection Bearded Ladies, been interested in giving voice to women who have been silenced.

“Yes, looking back I wouldn’t have ever said I was deliberately setting out to do that in a polemical kind of way, and yet clearly that’s my deeply held preoccupation. And obviously the fact that I keep writing about it means it hasn’t gone away as an issue for me, or for the world.

She does agree that there’s a Trumpian perspective to Mr Macarthur, who in Sydney quickly makes his way up the patriarchal ladder. She thinks of him as a blend of Donald Trump and a few other people I best not name for legal reasons. For this reader, the following passage has Trump all over it:

My husband was rash, impulsive, changeable, self-deceiving, cold, unreachable, self-regarding. I had learned all that, and thought it was the sum of him. Now I knew I was wrong. There was worse.

So, yes, he is all of those things and there’s more to come! Grenville laughs. “Absolutely! You have hit the nail on the head. Trump was literally in my mind as I wrote that.’’

I ask her about the political shift in Western liberal democracies, about the leadership of countries such as the US, UK and Australia. Her response is one word. “Leadership?”

Back in colonial Sydney, the Macarthurs are regular guests at gatherings organised by the governor and it is here that the other real historical characters come into the story, including “the always smiling Captain Tench’’ and “Lieutenant Dawes of the marines”.

Watkin Tench, the “Sydney Cove humourist”, who is writing a book about life in the colony, seems to fancy his chances with Mrs Macarthur. Her “memories” of him are hilarious. “An author,’’ she notes, perhaps on behalf of the author of her memoir, “was a dangerous acquaintance.” In an amusing coincidence, Tench’s real book, 1788, is part of the classics imprint of Text Publishing, Grenville’s publisher.

But it is Dawes, “our resident genius”, who might be even more dangerous, in a beautiful way. The title of the novel is the description of a secret outdoor place that he and Mrs Macarthur share. It is Dawes who introduces her to the stars, as he is an astronomer, and to the local indigenous people, whose language he is learning.

The line that makes me laugh out loud is when Dawes translates for Mrs Macarthur what an indigenous woman, Daringa, has just said. It is a reference to a story they have, he tells her.

Based on the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, they too have a tale about them that involves the chase of a man after women. What Daringa is saying, I fear with regard to me, is, that one is all right, but take care with his friend.

Your friend, I said. Who is your friend, Mr Dawes?

He glanced down at himself. I followed his glance and now, married woman that I was, it was my turn to blush.

There is a blush in one of Mrs Macarthur’s letters home, truthfully transcribed: “And I blush for my error.” The letter does mention Dawes, but in a different context. Yet those six words go to the heart of this novel.

When I ask Grenville about the cause, in her memoir as a novel, of that reddening of face, she thinks for a bit. “Well, one can only say there is nothing on the historical record that has so far come to light. But it’s a bit like science: you can’t ever say there isn’t a black swan because one day somebody’s going to find one.”

A Room Made of Leaves, by Kate Grenville, is published by Text Publishing on July 2 (336pp, $39.99 hardback).

On July 2, Grenville will discuss the novel in a streamed event hosted by the Wheeler Centre. Details: www.wheelercentre.com/events/kate-grenville-a-room-made-of-leaves

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout