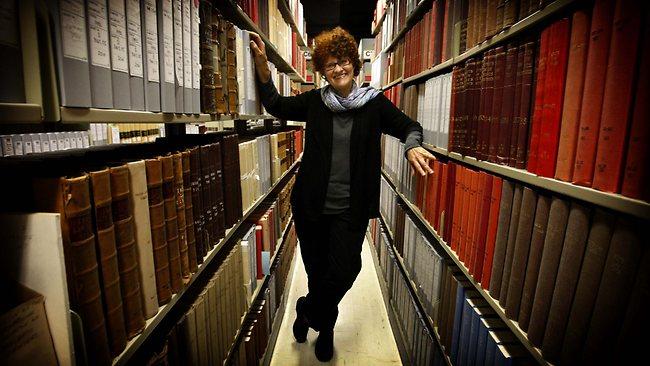

Kate Grenville creates a personal history in a colonial setting

KATE Grenville's enthralling new novel continues her emotional and ethical inquiry into our colonial past.

KATE Grenville's new novel, Sarah Thornhill, is not really the romance the jacket suggests, with its sepia-tinted heroine gazing off into Arcadia.

This marketing belies Grenville's reputation as a writer with a tough and pragmatic approach to the past. While there are gratifyingly romantic elements in this enthralling novel, they are underlaid by a discourse of remorse for atrocities committed against Aboriginal populations during colonisation.

In Sarah Thornhill, Grenville examines themes of guilt and conscience that are of continuing significance for Australians today.

This focus will not surprise those familiar with Grenville's award-winning and controversial 2005 novel The Secret River. Sarah Thornhill completes a loose trilogy of beguiling explorations of Australian settler history, which also includes her acclaimed 2008 novel The Lieutenant.

Sarah is the daughter of William Thornhill, the complex figure at the centre of The Secret River who, in the process of establishing his estate on the supposed terra nullius of the Hawkesbury River in NSW, chose a horrific course of action he was to regret.

In Sarah Thornhill, there are two poignant and delicately rendered love stories; Sarah moves on when the first one founders. Romantic love, however, is not the point of this novel. Coming to maturity, Sarah confronts the crimes of her father.

Born into the colonial situation, Sarah has played no part in its brutalities; nevertheless, she is assaulted by conscience. She is as innocent as those who, today, tackle the issue of saying sorry.

Her father has built a fortress of privilege, comfort and respectability, but she finds this legacy conceals a shameful burden. Sarah's story is based on apocryphal fragments of Grenville's family lore and scraps of information barely identifiable as documentation.

The novel is simply and beautifully narrated. Sarah tells it as it might be thought or spoken, in bits of sentences. She is illiterate but highly observant, sensitive to the splendour of her surroundings on the Hawkesbury River. Staying within the limits of Sarah's immaturity and understanding, the historical lineaments of the time remain indeterminate, slowed to the pace of domestic life.

Candidly, Sarah tells the story of her growing passion for a young Aboriginal man, Jack Langland. Her father, William, has taken Jack under his wing. Sarah believes her father is a noble soul and innately generous, offering gifts of food to starving indigenous neighbours and showing affection for Jack.

Sarah quietly imagines a life for herself and her lover. She records their ardour in a blaze of hope and openness that takes you with her, until it is unscrupulously snuffed out by her father and stepmother. Inevitably, Sarah is due for a brutal awakening. Yet we go so naively to that point, its arrival is crushing.

Traumatised, Sarah moves on with her life. She marries a decent, well-bred Irish settler, moves away from the Hawkesbury, and learns to love him. Just as Sarah's story appears, fairly happily, to resolve, another gathers pace.

William Thornhill has commanded Jack to fetch his orphaned, half-Maori grandchild from New Zealand and bring her to his grand home. The little girl is renamed Rachel by Sarah's stepmother, who is intent on erasing her origins. Rachel endures a fate akin to Mathinna in Richard Flanagan's 2008 novel Wanting. Tragically, Sarah fails to protect Rachel. Although she can have no control over the past, in Rachel's case she succumbs to socially ratified impotence.

The novel shifts from Australia to New Zealand and, perhaps, deeper into fantasy. Sarah is called on to make reparation. Her father's "cold charity", coldly received, will not suffice here. Sarah forces herself to leave her own baby and undertake the treacherous voyage to meet Rachel's grieving Maori relatives, where she will publicly call herself to account for the child's mistreatment.

Rather than deny, repress and forget, Sarah chooses to bear witness, accept and confess. It is an act of profound contrition, which achieves a measure of absolution. This final movement, combining Maori with Aboriginal suffering, makes the book begin to feel like therapy for a settler civilisation made neurotic by its discontents.

Sarah's story is not, then, about young love thwarted but the failure, during colonisation, of a larger love. It asks where ignorance ends and complicity begins. In her acknowledgments, Grenville notes that history has become a dangerous word for her to utter and emphatically states that this is fiction, not history. Yet is it that simple?

This novel revisits the fascinating, troubling territory of the history wars. It rows out on to the secret river of contemporary Australian anxiety (still running high, for example, in Sarah Maddison's Beyond White Guilt, reviewed in these pages on July 2) and navigates a fictional tributary.

Grenville's three novels have been deluged by commentary on her treatment of the Australian past, over and above discussion of their merits.

She found herself on perilous ground following the success of The Secret River, when historian Mark McKenna pilloried her for historical hubris, along with critics like me for not being critical. Following my riposte in this newspaper (Havoc in History House, 2006) the controversy ballooned (see Grenville's website at www.kategrenville.com).

In recent years, a forest of journalistic and academic work has rehearsed and extended the original spat. (Just last year, for example, Rodopi Press published Australian National University academic Kate Mitchell's Australia's "Other" History Wars: Trauma and the Work of Cultural Memory in Kate Grenville's The Secret River.) The novel, with associated commentary, turned up on educational curriculums. In the history v fiction debate, Grenville is totemic.

Why go back, then, to the ambitious, ruthless emancipist, William Thornhill, and the horns of his prickly dilemma? Why not just cut the history out of the fiction? Grenville's range extends well beyond historical fiction, as in the Orange award-winning The Idea of Perfection (1999).

She is, apparently, driven by the same compulsion that gnaws at other commanding writers, such as Flanagan, Pulitzer prize-winner Geraldine Brooks and recent Miles Franklin winner Kim Scott (That Deadman Dance).

For them, historical fiction is not just about dramatising the past but about tackling a contemporary "culture of forgetting", acknowledging history's "secret river of blood" (terms used in Australia's "Other" History Wars).

Grenville and Flanagan have convict ancestors; they take history personally. Scott is of Aboriginal descent. These authors are mindfully engaged in dialogue with the colonial past. Such fiction is a valuable form of emotional and ethical inquiry.

It is histories that are Grenville's concern. Sarah's story shows how unknown individual stories fill the past and create the present. Stricken Sarah, appalled by knowledge of her father's inhumanity, believes "there is no cure for the bite of the past".

However, the act of storytelling offers hope for a fuller understanding. Scott, in response to his Miles Franklin win, said: "There is a lot of reconciling - particularly reconciling ourselves to a shared history - that is yet to happen."

Grenville's vivid fiction performs as testimony, memory and mourning, within this collective, post-colonial narrative.

Stella Clarke has lectured on cultural and literary studies in Britain and Australia.

In The Weekend Australian Magazine today: Kate Grenville talks to Miriam Cosic.

Grenville is a guest of the Melbourne Writers Festival (until September 4) and Brisbane Writers Festival (September 7-11).

Sarah Thornhill

By Kate Grenville

Text Publishing, 295pp, $39.95 (HB)