John Russell: Australia’s French impressionist, AGNSW; van Gogh, Monet

John Russell was remarkably connected to so many important artists, yet his own work makes no serious contribution.

In his absurdist play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966), Tom Stoppard had the simple but brilliant idea of imagining the story of Hamlet from the point of view of two very marginal and minor characters, whose deaths at the end of the original play seem like a pathetic irrelevancy compared with those of its main characters.

Stoppard’s play, though something of a jeu d’esprit compared with Beckett’s more universally bleak vision in Waiting for Godot (1953), is still poignant as well as darkly funny, because he reminds us that we all live in the margins of other people’s tragedies, as they live in the margins of ours. Shakespeare himself hints at this in the casualness with which he has a messenger announce the end of people the audience had virtually forgotten.

John Peter Russell is similarly a painter who seems forever in the margins of Australian and European art at the end of the 19th and the start of the 20th centuries. At certain moments he seems tantalisingly close: thus, when we read about the career of Tom Roberts, we hear of a journey the young artist made through Spain in 1883, not long before he returned to Australia to set in motion what became the Heidelberg school, in the company of Russell and the even more obscure doctor William Maloney. We may also learn that the two corresponded for years afterwards.

Yet Russell had virtually no influence on the art that developed in Australia in the years that followed.

Or we may have realised, in reading about Vincent van Gogh, that Russell painted his portrait when they were in Paris together and that van Gogh considered this the best portrait painted of him. Or we may have seen some views of the sea crashing on the rocky cliffs of Belle-Ile in Brittany that are clearly inspired by Monet’s paintings of the same subjects.

It may dawn on us that this marginal figure in Australian art was surprisingly well connected in Europe, personally acquainted not only with van Gogh and Monet but also with Rodin and the young Matisse.

At last, all these scattered and rather puzzling elements, and many more that we didn’t know about, have been put together in Wayne Tunnicliffe’s monographic exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW, accompanied by a scholarly catalogue that includes several essays and much valuable documentation.

John Peter Russell (1858-1930) was born in Darlinghurst, Sydney, the son of a successful engineer, and was himself originally trained as an engineer and destined to take over the family firm. But as it happened his father wound up the business in 1877, then died two years later, leaving Russell independently wealthy. Accordingly, he travelled to London and then Paris to pursue his interest in painting.

He spent three years at the Slade School in London, where he learned the fundamentals of draughtsmanship — huge progress is visible between self-portraits in 1883 and 1886-87 — and then moved to Paris where he chose to study at the Atelier Cormon. This decision brought him into contact with a number of remarkable fellow students, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and van Gogh, who came to the school in the spring of 1886 on his arrival from Antwerp.

The exhibition includes the fine portrait that Russell executed of van Gogh as well as a remarkable sheet of pencil studies of van Gogh’s head, evidence of the solid training in draughtsmanship he had received at the Slade. He was certainly far better trained than van Gogh, who had only a few months of formal teaching in art. His portrait is confident and strong, while the small self-portrait by van Gogh that hangs next to it shows him still making an elementary, almost childish, mistake of perspective: the head is meant to be seen in three-quarter pose, but the eyes and nose are incongruously turned to face us directly.

Van Gogh’s image of himself is not only amateurish in technique but typically neurotic and unhappy in expression, while Russell’s portrait presents him as a confident and impressive artist. The portrait seems to anticipate his later fame, yet van Gogh would never be the confident master that Russell imagined. And it is important to remember that the man who would soon become something like the Arthur Rimbaud of modern painting was as yet completely unknown, merely an obscure Dutch art student who had been pursuing his eccentric, autodidactic course for half a decade in almost complete isolation, and was only now making contact with the art world of Paris.

Russell painted several other good portraits, including the self-portrait already mentioned, as well as likenesses of doctor Will Maloney and of American painter Dodge MacKnight. Unfortunately, he does not seem to have painted one of Roberts, nor of Marianna Mattiocco (1865-1908), a Calabrian who became his mistress in 1884 and then his wife in 1888. He did, however, paint a touching picture of her sitting naked on the beach, in the lapping water, in the summer of 1887, perhaps when she was pregnant with their second child.

When Russell married Marianna in 1888 he commissioned Rodin, who became another close friend, to execute a portrait bust, cast in silver. Rodin was fascinated by Marianna as a model, and the exhibition includes several other sculpted heads in different media; one of these, a plaster cast, has less personal character than the silver portrait, because it seems to be conceived more as a formal study of her features. But it reveals, even more clearly than the photograph Russell himself took, what was so striking about her: she seems like an ancient statue that has come to life, with a certain Calabrian earthiness and a gravitas that comes from child-bearing; still only 23 or 24, she is clearly a Hera rather than an Aphrodite.

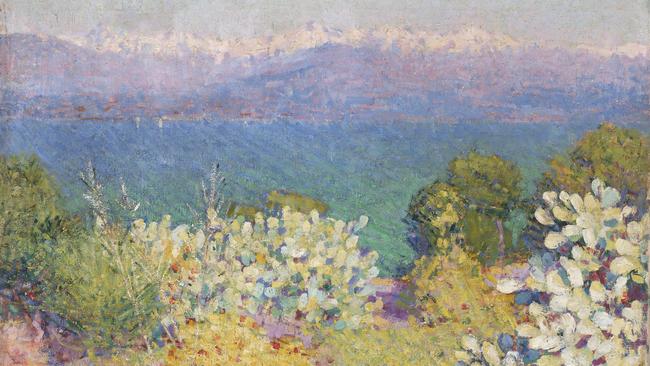

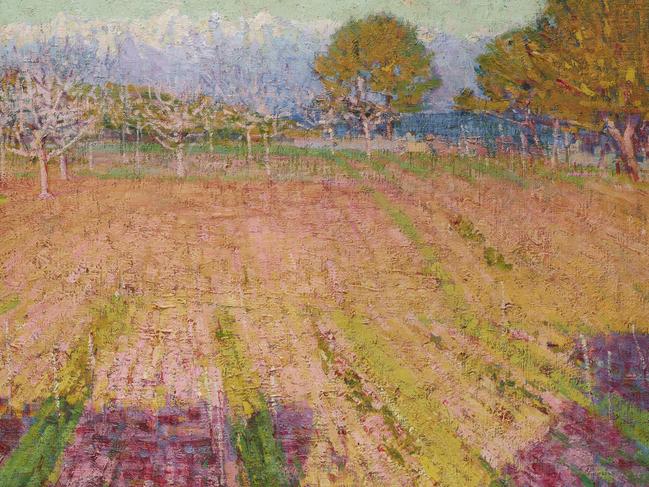

By far the most important influence on Russell as a painter was Claude Monet, who he met at Belle-Ile and who allowed him to watch him at work. Russell was clearly the opposite of van Gogh in temperament — confident, relaxed, friendly, easy to get on with. This meeting was decisive for Russell’s style as painter for, as we can see in the exhibition, he painted countless views of the same rocky coastline that had inspired Monet. After his marriage to Marianna, he moved to the island and built a large house there which became known as Le chateau de l’Anglais — for Australians were still generally seen, and even tended to see themselves until the Great War, as a subset of the British. Monet’s example must have seemed like a liberation, but it was also a kind of imprisonment, for Russell continued to paint views of the cliffs and the crashing sea for years afterwards. Some of these pictures are good but others are careless, and often they are poorly composed, for example with horizons far too close to the top of the composition.

Monet was capable of abolishing the horizon altogether when he looked down into the reflection of his lily-pond, but he was always decisive and he was steeped in the history of landscape painting so that he instinctively knew where the boundaries and conventions of the genre were, even — or perhaps especially — when he was taking the greatest liberties.

For Monet, the Belle-Ile paintings were one moment in an artistic journey that took him from an earlier obsession with optical appearance to an ever-deepening meditation on the nature of the phenomenal world, reaching, by the final years, the verge of mysticism.

But for Russell, Belle-Ile became a motif that he repeated without substantially advancing in his understanding of it or attaining greater depth of vision. Perhaps he was blinded by that glimpse of the genius of Monet; but while his training had equipped him with a reasonable grasp of the figure and the portrait, he was insufficiently acquainted with the tradition of landscape. He had nothing like Pissarro’s profound understanding of Corot, for example, which Pissarro in turn passed on to Cezanne. It might have been better for Russell if he had spent time with Pissarro — less spectacular but more capable of teaching him the fundamentals that he never properly learned.

Wealth may also have been part of the problem. Poverty can frustrate the career of a writer or artist, and a degree of independence is usually helpful. But wealth can be a more insidious threat, by removing constraints that are important stimulants to work. There have been independently wealthy artists of the first rank, such as Gericault or Manet, Degas until his family lost their money and Cezanne after he inherited his father’s fortune. But if wealth means one does not seek to publish or exhibit, it effectively consigns one to the rank of amateur.

The danger of being an amateur is that you do not develop: for it is only the hard work of writing, painting, composing for a public and for a market, for deadlines, that leads to the growth of skill and confidence. And even more importantly it is only that engagement with a community of our fellows that leads us to grow in our thinking and our vision as we effectively address our fellow human beings.

This is one of the ironies of Russell’s career. He was so remarkably connected to so many important artists, and yet his own work, appealing as it often is, does not really make any serious contribution to the history of art. It certainly makes no contribution to the evolving art of Australia in the same period, for he is simply absent when the Heidelberg movement is taking shape, with its conscious attempt to articulate the experience of Australians in the decades leading up to Federation.

The contrast with Roberts is striking. After some years of training in Europe and the famous trip through Spain, Roberts returned to Australia and was soon painting en plein air with Frederick McCubbin and Louis Abrahams, before meeting the younger Arthur Streeton. Meanwhile, Russell was in correspondence with Roberts, telling him about the new developments in contemporary art in France and explaining the meaning of colour theory.

But this was of limited use to Roberts: he instinctively knew he needed to find a pictorial language capable of expressing distinctive qualities of experience, and the elements that went into the Heidelberg style, so different from those that make up French impressionism, were perfectly adapted to his end. That is why the Australian artists of this period are so much more interesting than the contemporary American impressionists. The latter were derivative imitators of a style that becomes arbitrary and increasingly meaningless in imitation, whereas the Australians were forging new meaning.

John Russell: Australia’s French impressionist

Art Gallery of NSW, to November 11.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout