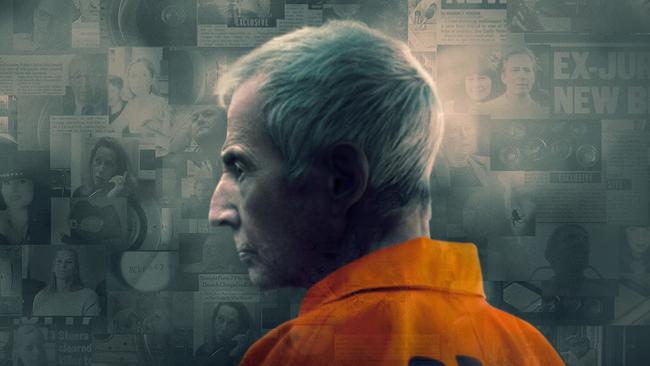

Jinx Part Two is the final chilling chapter in Robert Durst’s story

A factual reimagining of US killer suspect ‘Bob’ Durst’s story, Jinx – Part Two, is one of conjecture but makes for hypnotic, intense and compelling television.

The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, Andrew Jarecki’s sensational docu-series about the notorious murder suspect continues to excite comment, criticism, and straight-out bewilderment. The sequel, The Jinx - Part Two, is really a continuation of the series following on from the jaw-dropping climax of the first season’s finale. And it continues the bafflement over Durst, who died aged 78 in a state prison hospital facility in 2022, prompting yet more speculation and conjecture.

Had Jarecki reached the limits of the true crime documentary? Was there really anything more substantial to say about Robert Durst after the sensational first season? Is it right to bend the truth in the interests of both narrative cohesion and entertainment? Is it ethical to turn killers into characters, problematic and insensitive to the victims and their families?

And perhaps above all else – why on earth did Durst agree to talk to Jarecki at such length on camera? “Still kinda putting that together in my own mind,” Durst, a grim little man, as arrogant and deluded as he is obviously crushed with emotional pain and confusion, and often almost touchingly fragile, says in the new series.

This complex story of human cruelty continues to engage and implicate viewers in profound and unsettling ways. It was a story that sparked unexpectedly personal, participatory and impassioned responses from its huge audience, and arguably led to the current TV true crime obsession.

Jarecki was one of the first filmmakers to explore true crime as a kind of dramatic extended journalism in which the producers enter the public domain themselves as a kind of detective, reconstructing the crime to supplement the public record. And like so much of recent so-called prestige true crime The Jinx was as much about Jarecki, a meta-commentary, self-reflexively about the show’s creator and the intensive process of researching and reporting on such a substantial story. (In the new season Jarecki features prominently again, asking questions like a cold case cop and answering them, too; there are sequences from the first season, characters constantly reference the series, and massive billboard for the HBO series feature garishly in the background.)

Much has changed since the show premiered and it’s a little hard to remember the sensation Jarecki caused with The Jinx nine years ago. It was a perplexing tale of murder and courtroom mischief which quickly presented itself as an expansive story of the way the US justice system is influenced by wealth and social status.

It also happened to be highly entertaining, as complex aesthetically as any classy feature film.

Jarecki forensically examined the life and times of the reclusive millionaire, the eldest son of New York real estate magnate Seymour Durst, at the heart of three killings spanning four decades and long a suspect in the notorious 1982 disappearance of his wife, Kathie.

Further suspicion was raised with the unsolved killing of his decades-long confidante, Susan Berman, who was found shot in the head at her Beverly Hills home in 2000, thought to be a key witness in the investigation into Kathie’s disappearance. Then there was the subsequent dismemberment of a Galveston neighbour of Durst’s where Jarecki’s story so sensationally began.

Durst had also – despite admitting to dismembering Black – shamelessly gotten away with all of it.

During exclusive interviews with Jarecki, Durst, who offered himself for interrogation after seeing Jarecki’s film All Good Things, which was based on Durst’s life, talked with startling candour for 21 hours. In doing so, he revealed secrets of a case that had baffled authorities for 30 years.

It ended of course with Jarecki confronting the oddly compliant Durst with a letter he wrote, one that was eerily like a note penned by Susan Berman’s killer. The block handwriting seemed identical, both misspelling “Beverly Hills” as “Beverley”. It appeared to be conclusive evidence.

Following the tense exchange, Durst used the bathroom, unaware that his microphone was still, as they say, hot.

And it was here that he appeared to confess while talking to himself, after having been confronted with the damaging evidence. “What the hell did I do?” he mumbles in the hotel bathroom, almost inaudibly. “Killed them all, of course.”

Jarecki says he wanted to do more on Durst, worth about $100 million when he died, because of what he calls the constellation of his helpers. And as they appear in the new season they’re a troubling bunch, Durst’s money such an attraction.

“What was fascinating and what drew me in when we heard from the preliminary witnesses is that it got into the territory that we had talked about when we were making part one, which was, how do you kill three people over 30 years and get away with it?” Jarecki told Variety. “It takes a village. Who are these people that helped him along the way? People that see themselves as very decent human beings and yet somehow are drawn into murder in some way. That’s what interested me.”

And as is clear from the start of the second series, it’s obvious that evil never operates alone as Durst’s support system reveals itself, desperate to stay as his parasitic courtiers, shrugging their shoulders at what he might have done.

The series follows much of the Los Angeles 2021 trial of Durst, who was convicted of shooting Berman at point-blank range in her home to guarantee her silence because, according to prosecutors, she helped him cover up Kathie’s killing. And Jarecki examines many of the Durst circle of enablers, all able to easily turn a blind eye to his misdemeanours.

It starts with audio of the frail-looking cross-dressing killer in prison on March 14, 2015, the day before that infamous finale was broadcast. He had been arrested that morning at a hotel in New Orleans by FBI agents who feared he was about to flee the country. “Bob” – he’s only ever called this – tells his lawyer how he was grabbed by federal agents, his capture covered later in the first episode.

“I had a revolver, a whole lot of money, like $80,000, um, what else, oh, and I had – I was using that, uh, you know, that phony ID,” he says. As always Durst is casual and a little offhand, as if none of this really matters. “Oh,” his lawyer says. “Yup,” Durst says. There’s a pause. His lawyer asks how he is. “I’m all right. I mean I’ve been here before.”

He talks to many others from prison, eliciting support for the forthcoming trial, including his former wife Debrah Lee Charatan, who makes a prison visit. She’s another powerful figure in New York real estate, willing to settle up his Hampton properties, worth she estimates more than $400 million. She’s an enigmatic figure, proud of her big hair, she tells him flirtatiously, and seems intimate with Bob’s affairs, is happy to see him and obviously support him.

We’re introduced to Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney John Lewin, the other central character early in the series, a self-described straight shooter, fond of sporting analogies, and a cold case expert. He’s disarmingly avuncular but it’s obvious that he’s determined to find the right narrative strategy to trap Bob.

He conducts the first interrogation of Durst after his capture, reimagined by Jarecki with a stand-in, shot as if by surveillance cameras, using the original recording – a technique Jarecki favours. It’s like a scene from Michael Connelly’s The Lincoln Lawyer, Lewin expert at playing his defendant, helped by Bob’s chattiness. “Many times in Bob’s life, in custody, out of custody, Bob has an option,” Lewin says. “One door is keep your mouth shut, don’t say anything. The other door is talk. Bob always goes in the talk door.”

The episode takes us into the rabbit hole of timelines that bedevil The Jinx – the recapping clever and entertaining – and how, through evidence provided by the filmmakers, Lewin reopened the Berman case well before the final episode aired. And the way the FBI tracked him down to the Marriot hotel in New Orleans, Durst on the run, his abandoned Houston apartment sterilised, except for a bizarre box of mementos left on the bed. His new hotel room contained drugs, a firearm, and a map of Cuba. As well, there was a bizarre, expensive latex mask.

Once again Jarecki and his many collaborators – there’s a huge production list at the end with separate crews filming in four cities – entertainingly stretch the boundaries between fact and fiction, his approach highly aestheticised in the way he juxtaposes archival footage, interviews with key players, moody re-enactments, phone intercepts and prison recordings. This is immersive, pacy, hypnotic, and compelling TV, produced with imaginative intensity.

The Jinx – Part Two streaming on Foxtel and Binge.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout