James Cook’s 1770 voyage: new view at National Museum of Australia

A groundbreaking exhibition will tell the story of Captain Cook’s epic 1770 voyage from two perspectives.

Dora. Wanda. Esmae. Madge. Grace. Their names have an unmistakeable, old-world ring and indeed, most of these white and silver-haired painters are well into their 70s. From Hope Vale, a former Lutheran mission enveloped by dense rainforest and savannah woodlands in far north Queensland, these Aboriginal women lived through the assimilation era’s draconian controls, when their communities were often segregated from mainstream Australia.

Until the 1960s, by-laws in Cooktown, the nearest major town to Hope Vale, barred indigenous people from its streets after sunset.

“We had to get permission to go to town,’’ recalls Grace Rosendale, while fellow painter Dora Deemal remembers how she almost died from whooping cough when she was seven, and stayed in a hospital ward commonly referred to as “a niggers’ ward’’. In 1950, Madge Bowen’s mother was killed in a car accident. Aged six, she was placed in the Hope Vale girls’ dormitory, isolated from her extended family.

Decades on, these resilient women have come together to paint on the roomy veranda of the rustic Hope Vale Art and Cultural Centre, where overhead fans struggle to shift a stifling blanket of humid air. “It’s about communicating with friends. We’ve been to school together,’’ says Rosendale.

They like to laugh, too, chuckling over a collection of charity greeting cards depicting beefcake firefighters with bare, ripped torsos.

“They call ’em (these Hope Vale painters) the Gamba Gambas — old ladies!’’ interjects Esmae Bowen, who is in her 60s and helps out at the art centre. Today, she is wearing a practical, tradies’ two-tone work shirt. Out of the blue, she volunteers: “We also lost our husbands.’’

“Ten years this year,’’ pipes up one painter and the others chime in: “Mine will be three years … 17 years … 20 years for you too.’’ In this spontaneous accounting of loss, the appallingly low life expectancy of indigenous men from remote Australia is laid bare.

The women, who exhibited their work in Sydney in 2013, paint three days a week.

Today, despite their experiences of systemic discrimination, they are depicting a little-known chapter of a momentous event that led to colonisation and the dispossession of their people: Captain James Cook’s 1770 voyage along the east coast of Australia.

Specifically, the Gamba Gambas are interested in the explorer’s encounters with their ancestors after the HMB Endeavour was nearly wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef.

Two-hundred-and-fifty years ago, Cook claimed eastern Australia for Britain. Despite deep divisions over how to mark this anniversary — the Greens have said commemorative events should be scrapped — the Hope Vale painters have created a suite of vibrant lightboxes (or backlit paintings) for a groundbreaking, $3m Endeavour voyage exhibition mounted by the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

From mid-June to early August in 1770, Cook, botanist Joseph Banks and the Endeavour crew spent almost seven weeks repairing their stricken ship and exploring the area that later became Cooktown, after the Endeavour ran aground on the reef.

It was the longest period the explorer and his crew spent on the Australian mainland, and during that time they had six recorded encounters with the local Guugu Yimithirr people, whose descendants still live around Cooktown and Hope Vale.

The exhibition, titled Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians, is to be launched online in late April, close to the date (April 29) when Cook first set foot on Australian soil at Gamay Botany Bay.

The online exhibition runs until October and if the coronavirus pandemic eases before then, the Canberra museum – which closed down in late March because of the virus threat – will reopen its doors, and also show the physical exhibition to the public. Based on two years’ exhaustive research with indigenous communities scattered along Australia’s east coast, the exhibition seeks to reshape our nation’s first contact history, by telling this foundational story from two perspectives — the shore and ship.

NMA director Mat Trinca says Cook’s voyage “lies at the centre of our history and we’ve told it very much from the conventional viewpoint. But we know very little in wider Australian society about the view from the shore, and it’s time for it … For Aboriginal people, of course, Cook becomes a synonym for all that happens after, and understanding that is important.

“For the first time, we are also seeing and hearing the views of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders from communities up and down the east coast that are connected to that more established narrative. The people whose voices you’ll hear in this exhibition from those communities are the descendants of people that saw Cook and his men sail along the coast.’’

Trinca rejects Greens MP Adam Bandt’s view that the 250th-anniversary events should be ditched, as they are not “honest about the dark sides of Australian history’’.

“I don’t think history is ever about erasure or should ever be about erasure,’’ he says. “It is about the accretion of layers of meaning over time. How can you argue that we can just forget our past, rather than taking the opportunity that’s presented here to reflect upon it, to see it from a wider series of perspectives than we have to date, and to learn from that?’’

Endeavour Voyage focuses on stories from seven east coast communities, including Point Hicks in Victoria, the first Australian landform spotted by Cook’s crew; Kamay Botany Bay, where a Gweagal man was shot while trying to prevent Cook from coming ashore; Cooktown/Endeavour River (Waalumbaal Birri); and Possession Island, off the tip of Cape York, where Cook claimed all of the lands that lay south of that 5.5sq km speck for King George III.

RELATED: NGA’s Know My Name | Captain Cook: Fresh visions of an epic life

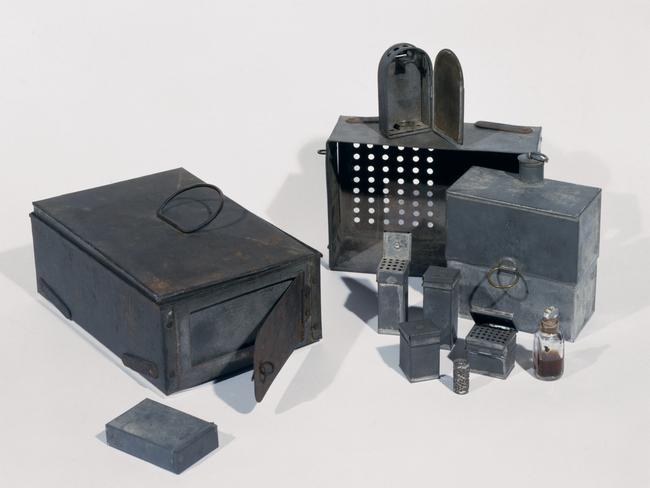

Review understands NMA staff were well underway with installing the physical exhibition when the museum had no choice but to close its doors. It is envisaged (subject to further virus-induced delays) that an enhanced online show – which staff are now frantically working on – will feature a virtual tour of Cook’s journey along Australia’s eastern coast and a film by indigenous filmmaker Alison Page bringing to life the indigenous view from the shore as the Endeavour sailed past. Highlighted objects include the Cape York art works, Nathaniel Dance’s 1773 portrait of Cook, which hung over botanist Joseph Banks’s fireplace and a cannon that was tipped overboard when the Endeavour was snagged on the reef. An interactive botanicals display will allow viewers to click on famous sketches supervised by the Endeavour’s botanist, Joseph Banks, and learn about the indigenous history of those plants.

Trinca says: “We feel deeply for the Indigenous communities and museum staff who have worked so hard together on this exhibition over the past couple of years and hope we are able to open our doors in time, to allow the public to see this ground-breaking show for themselves. In the meantime, we hope audiences are engaged by the rich digitised version of the exhibition which reframes the way we consider this historic moment.” (If and when it opens, The Endeavour Voyage show will be free. It was directly funded by the Federal Government as part of its broader, $50 million package of projects to mark the 250th anniversary of Cook’s east coast expedition.)

Exhibition curator Ian Coates says that in 2017, the NMA decided to “work with the descendants of those indigenous people who were there in 1770, and start talking about what those events mean to them’’. The museum soon discovered that “there’s not a simple, alternate narrative that sits alongside the Cook one; it’s much more complicated”.

Interestingly, while the Hope Vale women consider the introduction of Christianity and modern innovations as positive repercussions of Cook’s historic voyage, they also point out that it led to colonists “taking our land’’.

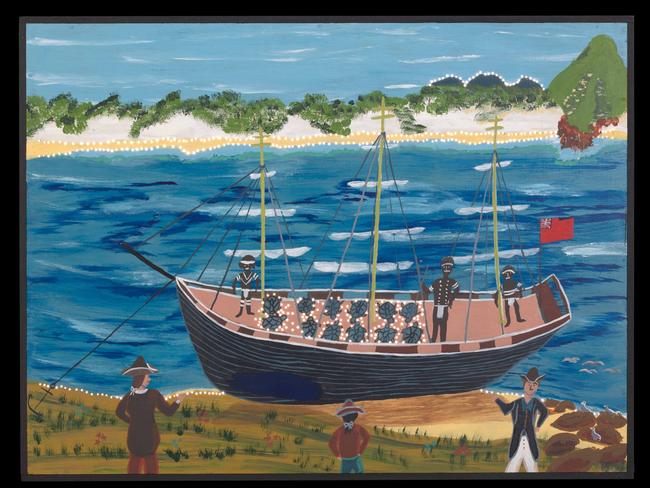

While Cook’s widely documented Botany Bay landing ended in violence, in Cooktown there was a historic act of reconciliation that eased tensions between the explorer’s party and the Guugu Yimithirr — and it was initiated by an Aboriginal elder. Hope Vale artist Wanda Gibson says this elder — described as a “little old man’’ by Banks — was her grandfather’s ancestor. “I had the privilege of painting that picture,’’ she says, almost shyly. Her backlit painting, No Blood Will Be Shed, is part of the NMA exhibition and captures the high drama and tension of that moment, which was described in detail in Banks’s Endeavour journal.

“The little old man now came forward to us carrying in his hand a lance without a point …. We beckond to him to come: he then spoke to the others who all laid their lances against a tree and leaving them came forwards.’’ From the Endeavour journal of

Sir Joseph Banks

On July 19, 1770, tensions between the Guugu Yimithirr people from the Cooktown/Endeavour River area and Captain Cook and his stranded crew threatened to erupt into a bloody feud. Accounts from the journals of Cook and Banks make it clear both parties were minutes away from armed conflict when the “little old man’’ stepped forward.

Roughly one month earlier, the Endeavour barely made it ashore after it was seriously damaged on the Great Barrier Reef. The ship was stuck fast on the reef, and sucking in water through a hole in its hull, for almost 24 hours. A homespun repair job, a sail covered with sheep’s wool and dung to plug the hole, was all the desperate crew had to stop the vessel from sinking.

Cook and his crew spent 48 days ashore at Endeavour River and repaired the Endeavour, hunted their first kangaroo and conducted extensive botanical research. They also recorded 132 indigenous words including “ganguuru’’ — the Aboriginal word for kangaroo. Those words are believed to be the first written record of an indigenous language in Australia.

But on the morning of July 19, tempers flared when the explorer refused to allow Guugu Yimithirr men and women who were aboard the Endeavour to return to the water two of eight to 12 turtles the crew had caught. Enraged, Aboriginal men twice set fire to Cook’s riverside camp.

In an exhibition note, Gibson explains that “taking too many turtles without permission from traditional owners is against our law’’. Cooktown’s indigenous historians told Review the Guugu Yimithirr wanted to return female turtles to the reef because it was breeding season; they regarded the taking of so many animals at once as environmental vandalism.

Cook retaliated over the acts of arson, firing a musket loaded with small shot at one of the “ringleaders’’. He later wrote that the indigenous men had been armed with “four or five darts (spears) a piece’’.

Suddenly, near a cluster of boulders by the Endeavour River, an Aboriginal elder — “the little old man’’ — stepped forward, carrying his spear with the tip broken off.

Taking their cue from the elder’s conciliatory gesture, Cook’s crew returned several captured spears and the explorer wrote that everything was “reconciled’’.

Two-and-a-half centuries on, indigenous and non-indigenous historians say this incident should be officially recognised as the nation’s first recorded act of reconciliation. Coates says: “That moment of reconciliation — Cook calls it reconciliation — is one that we should be making much more prominent in our knowledge of the origins of this nation.’’

According to Gibson, the site where the hostile parties put down their weapons — known today as Reconciliation Rocks — “was a special place where disputes had been traditionally resolved. Cook and his men were very lucky. No blood had been shed”.

This reconciliation milestone is little-known outside Cooktown, and the Endeavour Voyage exhibition gives it a national platform.

The explorer and cartographer’s Cooktown visit was historically significant in other ways. Coates speculates that if local clans had not granted Cook and his crew ample time to repair the Endeavour, they may not have survived their near-shipwreck, and history could have played out differently. “We could all be speaking French,’’ Coates says. “The French were very interested in this part of the world.’’

In a further stroke of luck, Cook landed on the Endeavour River’s southern bank, on ground indigenous people considered neutral; a place where conflict was forbidden. If they had come ashore on the northern bank, several local indigenous experts told Review, they would not have survived. On such slender threads did Cook’s survival — and the future colonisation of Australia — hang.

Why isn’t the Cooktown reconciliation story better known? “I think it’s a Sydney-centric thing,’’ says Coates. “When people think about Cook in 1770, they think about Botany Bay. They think about the first moment where he landed.’’

“Why isn’t Cooktown better known?’’ repeats the town’s mayor, Peter Scott, rhetorically. “It’s an idyllic spot which was very isolated before the road (from Cairns) was sealed up (in 2011).’’ Today, Cooktown is a largely white town with a rich history, incredible scenery and rude juxtapositions — you can find a vegan lentil curry at one cafe and just down the main road a Thai restaurant called Jacky Jacky.

The town’s growing tourism industry is leveraged around the Cook legend. Its main attraction is the James Cook Museum, which features an enormous black anchor and cannon from the Endeavour; and one of its drawcard events is an annual re-enactment of Cook’s encounters with local Aboriginal clans (July’s 250th-anniversary event, grandly named Expo 2020, has been postponed until 2021 because of the coronavirus outbreak).

Scott concedes Cook’s voyage led to “a lot dispossession and awful stuff’’ for indigenous people. “It even happened here in Cooktown during the goldrush days. … The local people out here were driven off their country. But that’s not the story we’re telling here. Our local indigenous people — the direct descendants of the people who met Cook — they’re focused on telling the (reconciliation) story.’’

In Cooktown, the indigenous side of the story is still being proudly reclaimed: the James Cook Museum, housed in a magnificent 19th century former convent, is being reconfigured to tell the story of the area’s first peoples first. The somewhat neglected Reconciliation Rocks site — near the banks of the sinuous (and croc-infested) Endeavour River where the 1770 rapprochement occurred — is set to be upgraded with a $1.3m grant, and the National Trust of Queensland has applied to have it included on the National Heritage List.

“We see this as such an incredibly significant site,’’ says Scott, calling for Australian school curriculums to incorporate the reconciliation tale.

Self-described “unlettered historian’’ and local elder Alberta Hornsby only started learning the details of the extensive contact between Cook’s party and the clans she descended from about 10 years ago. “These things to me are amazing,’’ she says. She grew up assuming her ancestors were nomads, but Cook’s journals suggest otherwise. “Coming to see it (Aboriginal history) from these journals … it’s really powerful and uplifting, and it’s about time Australia knows about it.’’

Indigenous artist Daniel Gordon is taking part in the NMA exhibition, and his view of Cook’s legacy is much darker. He is from the Cape York community of Wujal Wujal, and he says that after Cook’s 1770 voyage, “they brought in the other mob (the First Fleet) and they ran amok. Treated Aboriginal people like slaves. That’s when the real trouble started’’.

He says Aboriginal people still feel hurt by the past mistreatment of their grandparents and great grandparents: “We’re going ahead now, but the feelings are still there.’’ Given his scepticism, why take part in the exhibition? “When you are putting these paintings in the exhibition, you are giving the artists a name — that is the good part of it,’’ he says. He also welcomes the show’s dual shore and ship perspectives.

Coates says this exhibition goes further than others have at presenting indigenous perspectives on the Cook narrative. Highlighted quotes from Cook’s journal are juxtaposed with answering quotes from indigenous people, while the Kamay Botany Bay installation — featuring spears taken by Cook in 1770 alongside contemporary spears — was designed by that community.

Harold Ludwick worked on the NMA show and is an indigenous heritage officer at the James Cook Museum. With his baseball cap, reflective sunglasses and neatly trimmed goatee, he does not fit the stereotype of a professional museum nerd, but he has studied Cook’s journals closely, and says they cannot be properly understood without taking into account indigenous perspectives and knowledge about the things the explorer observed on his 1770 odyssey. “Cook’s writing itself acknowledges that Aboriginal people were living here,’’ he says. “It’s a great story because they record that terra nullius does not exist. It blows that myth out of the water.

“It is vitally important that we celebrate what was recorded, because what was recorded (by Cook) brings to life our people practising civilised ways before the First Fleet arrived. Cook gave us a platform; we are an integral part of that journal.’’ To those who argue the 250th anniversary should be ignored to spare indigenous people’s feelings, he says: “The story of Cook hasn’t been finished. The story is still open and we are the bookend.”

Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians launches online in late April at the National Museum of Australia website. Go to https://www.nma.gov.au/

Rosemary Neill travelled to Cooktown with the NMA’s assistance.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout