Ink in the Lines exhibition: These scars tell a story

Tattoos may be a way of dealing with the trauma of war, but they are also a way for veterans to connect with other people.

Human experience of war is not universal or evenly distributed; people who lived in most parts of the Roman Empire enjoyed centuries of peace, while on the frontiers, the legions kept marauding barbarians at bay. The same is true of life in other large and well-run empires, from the Persian or Chinese to the British. In many tribes, on the other hand, a young man does not properly come of age until he has fought in a battle or in some cases until he has killed another man and even cut off his head.

Even in much more sophisticated societies, soldiering can be a part of every man’s life. The decentralised nature of Greek civilisation, based on the independent polis rather than on a large state or empire, meant that citizens had to be self-reliant, and military service was universal. Military training began at 18 and men were liable for call-up in the event of war from 21 to 60. This system naturally disappeared after the individual cities were forcibly united under Philip of Macedon in the 4th century BC.

In modern times, compulsory military service appeared in the great industrialising states of the 19th century and produced the massive armies of modern times, even though Australia rejected the suggestion of a compulsory draft during World War One. The two disastrous world wars of the 20th century thus involved what was undoubtedly the greatest number of combatants in history, producing corresponding levels of casualties.

Both my grandfathers were in the Great War, and one commanded Australian troops in the Second World War; my father also fought in the Second World War. Those of us born since that time, apart from those called up for the war in Vietnam, have been largely spared this ordeal, not because Australia has not been involved in military operations of various kinds, but because such operations today require smaller and better-trained forces rather than large armies of conscript cannon-fodder.

In a number of recent theatres of war we have come to rely on even more highly trained special forces to fight unconventional wars against opponents using guerrilla and terror tactics. In these operations, numbers are less important than agility, daring and resourcefulness. As it has turned out, we may have over-relied on these soldiers, putting them under enormous strain and unintentionally fostering a regressive tribalistic culture among lower ranks.

It is probably impossible for those of us who have not been to war to understand what it is really like, even if great literature – from Homer to Tolstoy – and cinema have given us glimpses of insight.

Video and computer games achieve the worst of possible outcomes, desensitising their users to the idea of violence, while alienating them from all its realities, including bodily pain and death.

Physical pain as well as intense discomfort and distress are some of the more obvious sufferings associated with war, but unless they lead to death or permanent disability, they are temporary. As we have realised with increasing clarity since the Great War, however, psychological scarring can be more intractable. It was originally called “shell shock”, because the men seemed to have been reduced to a state of nervous breakdown by the unrelenting horror of shelling in the trenches, although their suffering was clearly also caused by the horror of killing and seeing their comrades killed.

Today we refer to these experiences more generally as trauma, which is a Greek word meaning a wound. The condition that arises when these psychic wounds fail to heal properly and continue to cause psychological distress has been known since the 1970s as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

As with many psychological diagnoses today, we have to ask whether we have had an increase in the condition itself in the contemporary world, whether we are diagnosing it more effectively today, or whether we are perhaps over-diagnosing. Another important question is to ask what factors may help or hinder the healing of psychic wounds, especially when we see that PTSD appears to be notably more prevalent in America than in other parts of the world (according to the American Psychiatric Association, the US Dept of Veterans’ Affairs, and other sources).

The fact that the diagnosis arose in the course of dealing with veterans of the Vietnam War may give a clue – this was the first time that American soldiers fighting in an overseas war did not feel fully supported on the home front, and in the years that followed they felt their nation was ashamed rather than proud of their efforts. Men who fought in earlier wars might suffer the trauma of death and killing, and carry these wounds for the rest of their lives, but the burden was easier with the solidarity and admiration of the community.

More subtly, the experience of demobilisation has always been hard; my grandfather wrote eloquently to my father about this after the Second World War, comparing the transition to swimming across a fast-flowing river, and describing the sense of banality and insignificance that the former soldier feels in the civilian world after the danger and responsibility of his military life.

But all of this must be even harder when the soldier returns to a disoriented, morally confused and fractured society.

Tattoos, as this exhibition shows, are a means of dealing with trauma through inscribing it on the body, at once displaying its indelible scar and purging it through the experience of pain and the re-enactment of grief. In the mildest cases, it is perhaps simply a longing for the intensity of comradeship and the sense of purpose and of doing something significant.

One young woman, observing that she knew Afghanistan would be among the biggest things she would ever do, had the name of the ancient city of Kandahar inscribed on her foot in Persian script.

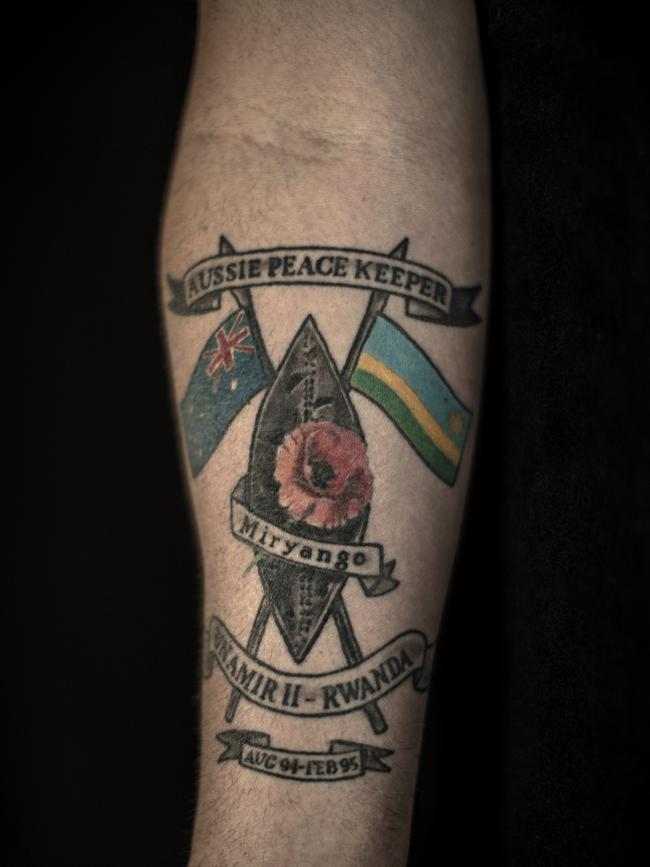

Others have experienced trauma on peacekeeping missions where they were not themselves under fire, but witnessed the brutality inflicted by one local group on another and the sufferings of those who were displaced, wounded or orphaned as a consequence of the conflict.

Sean, who took part in Operation Solace in Somalia in 1993 and was photographed by George Gittoes as a young man in Somalia holding a little child in his arms, subsequently got a tattoo showing the map of the Horn of Africa and a magnifying glass identifying the location of his regiment’s base at Baidoa.

The most extreme cases of trauma, however, arise from the loss of a comrade, generally on the battlefield but sometimes subsequently to suicide. The bonds formed between fellow-soldiers have always been strong ones, and they are perhaps relatively stronger still today when other social connections have been weakened. To see someone with whom you have formed such a strong attachment under fire suddenly killed before your eyes is evidently devastating, as is confirmed by the moving testimonies of several men interviewed in the videos that are discreetly set in each room of the exhibition. You can feel that these men have quite literally never been the same since – youth, energy, optimism and even physical robustness and health have all been shattered.

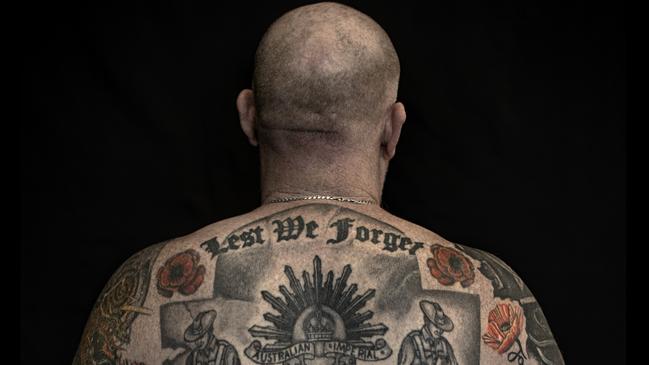

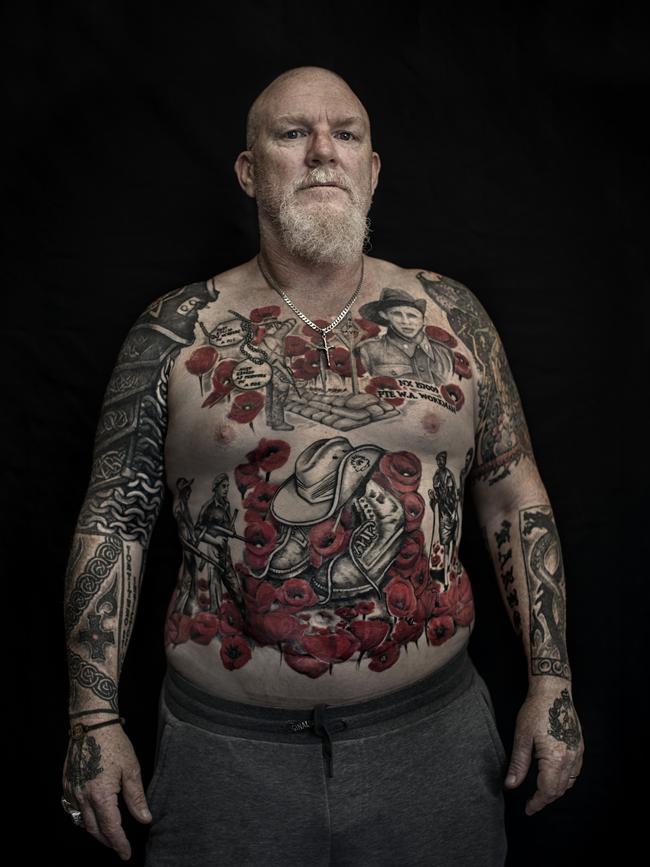

Many of them then have memorials of their dead comrades tattooed on their arms, chests or backs – sometimes portraits, sometimes dog-tags with their names, or pictures of their graves, often surrounded by poppies. One man’s shoulder and upper arm are covered with the reproduction of a photograph of himself and other soldiers escorting the caskets of three dead comrades home in a Hercules transport. One has the whole front of his torso covered in commemorative scenes, ending in a sea of red poppies.

The pain of tattooing is always a part of the experience – even for the many civilians who choose to have themselves tattooed – and here it is explicitly discussed by several individuals, sometimes because it draws them out of the numbness of their traumatised state and makes them feel something again, and sometimes because it seems to expiate traces of the guilt that survivors often feel in these circumstances. One man observes that it is “like punishing yourself”. Several men refer to the pain as therapeutic.

The principal object of these designs is clearly to remember those who have died, and indeed several include the whole of the “They shall not grow old” verse, from Laurence Binyon’s poem For the Fallen, originally published in the London Times in 1914.

But there is also, conversely, the need to forget. One of the tattoos already mentioned includes the words: “Only the dead have seen the end of fear.” Another man has a ferocious dog attacking with bared fangs, an image of terror, and the iconography of skulls and other images of death is ubiquitous. It is significant that the veterans are much more likely to talk about their lost comrades than about the dark and nameless terrors such imagery evokes.

“I needed to put stuff behind me,” one man observes. Part of that process is acknowledging the causes of fear, and perhaps fixing the ever-shifting nightmare into a single stable image that can be looked at squarely.

There are likewise analogies with rites for the dead in many cultures around the world, which involve ceremonies of honouring and commemoration, but also of ritual separation, and of putting the dead to rest so that they can stop coming back to haunt us.

And yet one of the most important functions of these tattoos seems to be in opening connections with other people, as will be apparent to anyone who listens to what the veterans say, or who reads some of the material on the excellent War Memorial website pages devoted to this exhibition and the underlying research project.

David, for example, who was in Afghanistan in 2011 and wears a tattoo of an armoured truck in Mirabad Valley, “hopes that when people see his tattoos they will recognise him as a veteran and ask about his experiences”. In his case, and in some others, we feel that the designs are like mnemonics or emblems, intended to epitomise an experience that can be expanded on in telling, remembering, and in the process laying memories to rest. Christine too, who has a striking tattoo of a man and woman embracing on her back, hopes that people will ask about it.

One man observes that having a tattoo is “like an icebreaker that lets people talk about it” – in other words that gives the veteran an opportunity to speak about his experiences instead of living with them bottled up inside.

Perhaps the most touching case, because it poignantly recalls the loneliness of those who have experienced what those around them can barely imagine, is that of Paul, a former military cargo operator, who hopes that his tattoos will make someone in a pub ask him about them, and “start a conversation”.

Ink in the Lines