Imprisoned and impoverished, Sulu’s real-life journey as an ‘enemy alien’ in America

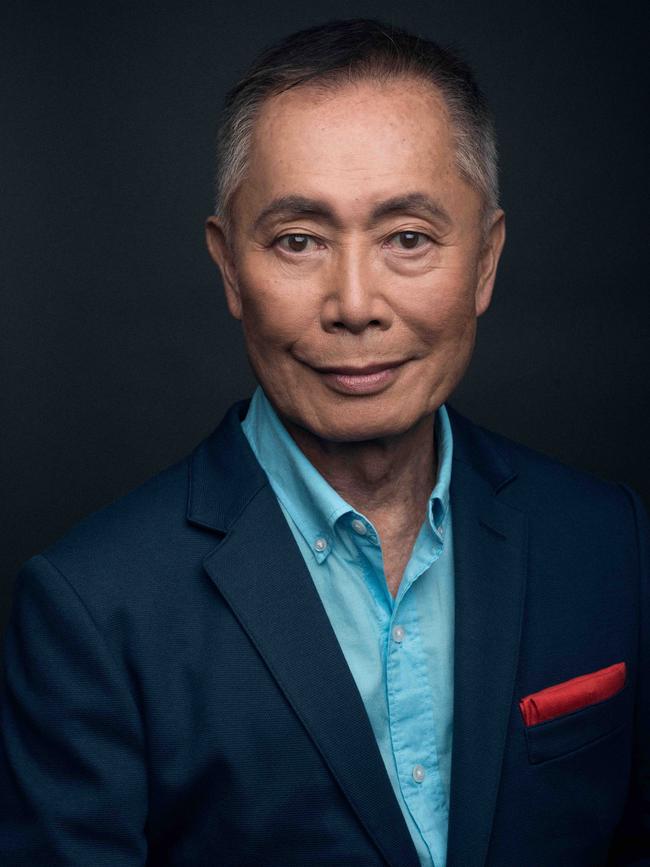

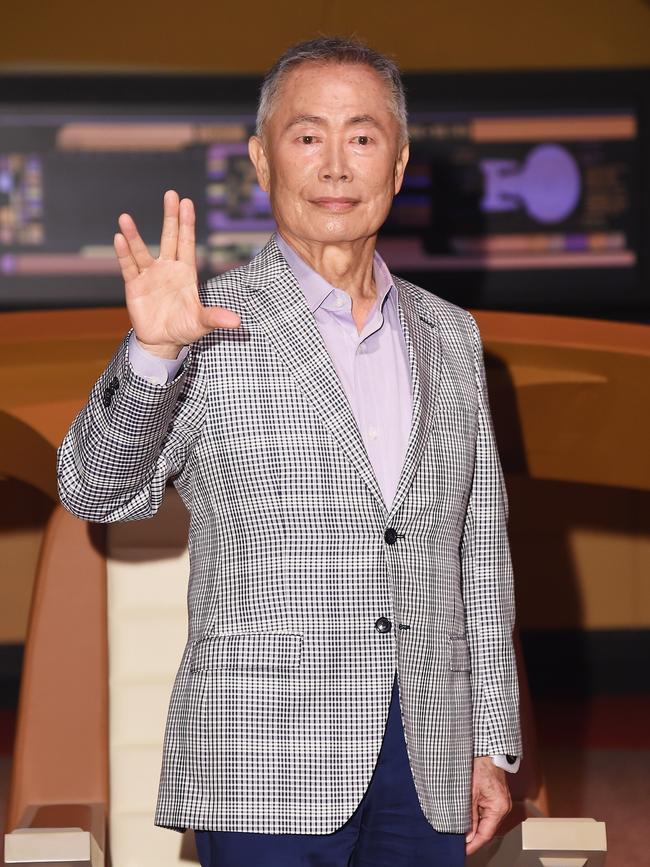

Star Trek legend George Takei opens up about his involvement in a shocking chapter of American history, working with ‘insecure, arrogant’ William Shatner — and why he stayed closeted until the age of 68.

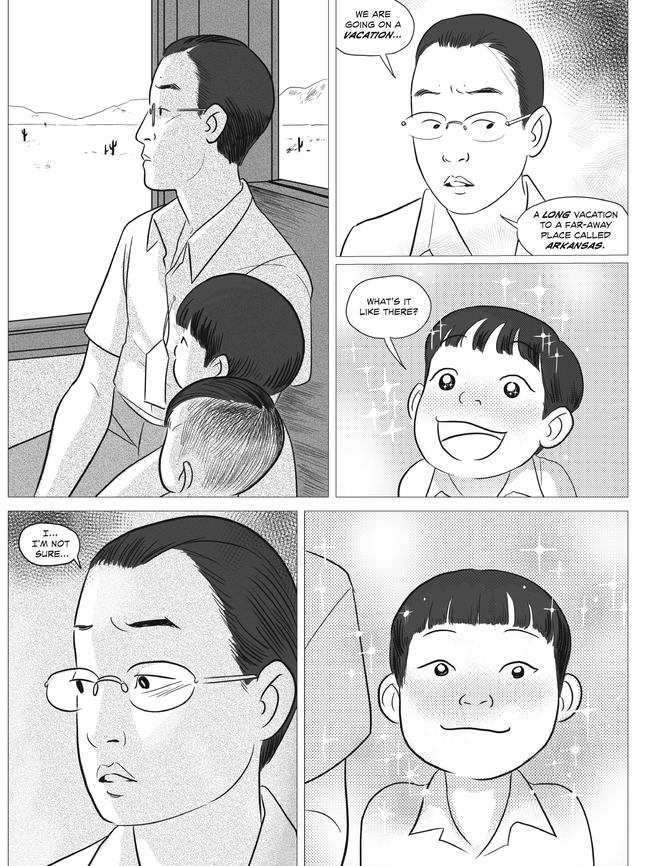

George Takei vividly remembers when, at age four, US military police arrived at his home in Los Angeles in the spring of 1942 and ordered his family to immediately depart for an internment camp for the duration of World War II.

Under president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order 9066, Takei and his father, mother, brother and baby sister were among the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were imprisoned and lost their homes, jobs, businesses, assets and belongings.

“They impoverished us, imprisoned us and put us in barbed-wire confinement,” Takei, 84, tells Review via Zoom. “Tule Lake was the largest of the internment camps with over 18,000 people and grisly with militaristic armament: three layers of barbed wire fence, sentry towers with machine guns and patrolled by half a dozen tanks.”

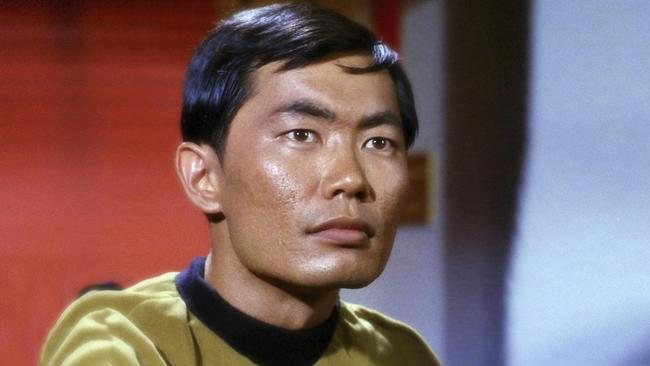

In 1965, Takei would be cast as helmsman Hikaru Sulu in the television series Star Trek (1966-69). That show, the animated series (1973-74), and six movies with the original cast (1979-91) spawned a cultural phenomenon that led to spin-off shows and movies in the decades after.

Takei notes that he is the son of Japanese immigrants who boldly went to a strange new world in search of a new life and opportunities. His father was born in Japan; his mother in California. They married, worked and raised a family in the US.

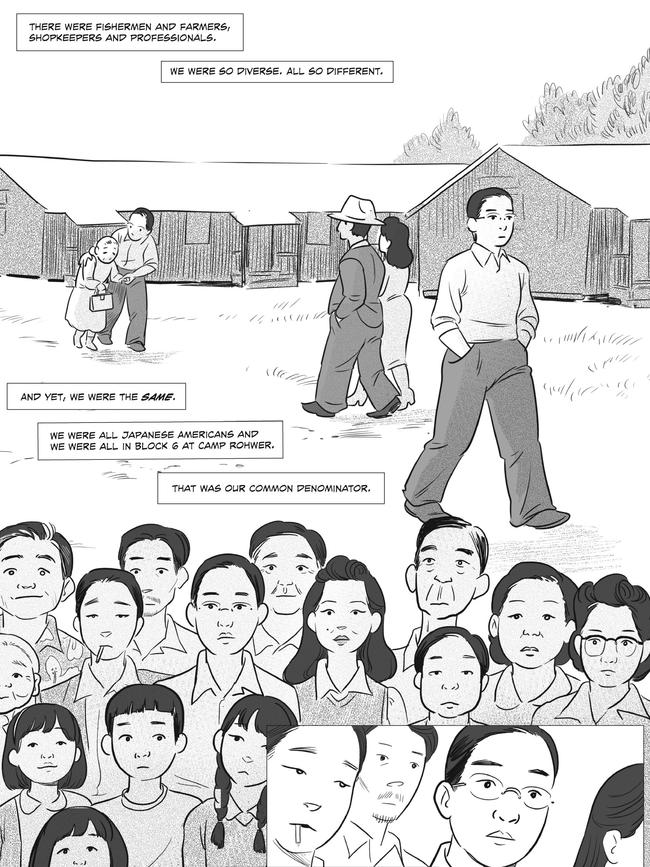

After Japan attacked the US naval base at Pearl Harbour, any person of Japanese ancestry was declared an enemy alien. The Takeis were sent to live in adapted horse stables in Arcadia and then to “relocation centres” in Rohwer (Arkansas) and Tule Lake (California).

The story of Takei’s childhood has been told in his memoir, To The Stars (1994), and rendered as a graphic novel for a younger audience. From the opening pages of They Called Us Enemy (2019), readers are immersed in those traumatic events that took place 80 years ago this year.

“Whenever I shared my childhood imprisonment, even with people I considered well read and well informed, they were shocked that something like this happened in America,” he says. “I wanted to reach a new generation and I loved comic books as a teenager, so I did it as a graphic memoir.”

Takei did not fully understand what was happening or why. He remembers the suffering and disappointment of his parents because he saw it in their eyes. He had to tell two stories: their heartbreak, and his wide-eyed adventure and confused terror.

“I wanted to preserve my memories,” Takei explains. “But as an adult I had been haunted by my lack of knowledge. I had to do more research. Two parallel stories: my parents’ anguish and my own innocent sense of discovery. I wanted to keep that dual aspect.”

The internment did not make Takei’s parents bitter or distrustful. Takei’s father encouraged his children to be involved in the political process. Takei was elected to student government positions and the family volunteered for Adlai Stevenson’s campaign for president in 1952.

“Japanese Americans lived through the darkest breakdown of our democracy and yet my father understood the nobility as well as the fragility of the ideals of this country and its participatory democracy and explained that it is vitally important that good people cherish those ideals and be active participants in that process,” Takei recalls.

It is extraordinary that given the racial prejudice he endured as a boy, Takei was later cast in a series set in a fictional future where common humanity mattered more than race, religion or gender.

It was hopeful and optimistic, as people from diverse backgrounds came together to navigate the final frontier of the stars. But it only became a hit in syndication, having been cancelled after its three-year run.

“It was a turbulent time in the 1960s,” Takei recalls. “We had the civil rights movement, the sexual revolution and the Vietnam War and all these issues were tumbling over each other yet television wasn’t reflecting that. So Gene Roddenberry came up with the idea of telling a story using metaphors and placing it in the 23rd century.”

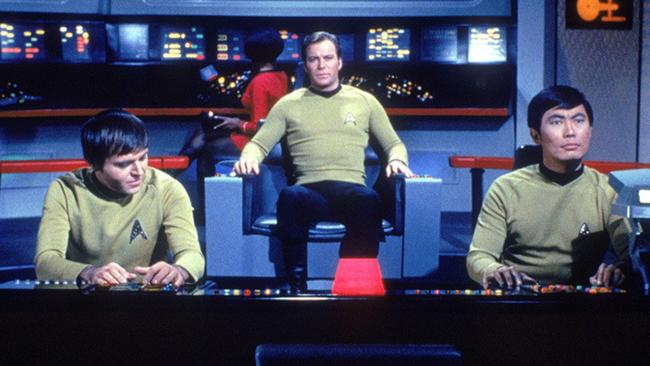

The diversity of the cast was groundbreaking: William Shatner as captain James T. Kirk, Leonard Nimoy as first officer Spock, DeForest Kelley as Dr Leonard “Bones” McCoy, Walter Koenig as navigator Pavel Chekov, Nichelle Nichols as communications officer Nyota Uhura, James Doohan as chief engineer Montgomery “Scotty” Scott and Takei as Sulu.

“The television series was not successful, I like to think, because it was so advanced,” Takei argues. “The Starship Enterprise was a metaphor for Earth and the idea was that the diversity of Earth working together as a team was its strength. You saw the diversity in Uhura and Sulu, you heard the diversity in Scotty’s Scottish accent and Chekov’s Russian accent.”

Takei has been candid about the on-set differences with Shatner. He believes Shatner was brilliant as Kirk but “never respectful” towards others and was not interested in “teamwork”. He describes how he was aloof, arrogant and insecure. Nimoy received three times the mail that Shatner did, which made him jealous and at times petty.

While studying acting at university in the late 1950s, Takei was cast in theatre, television and film roles. He had small parts in shows such as Perry Mason (1959), The Twilight Zone (1964) and My Three Sons (1964-65) before Star Trek. Although a leading advocate for LGBT rights, he did not reveal he was gay until 2005.

“My career would not have been possible,” he explains. “In the 1950s and 60s, no gay person would be hired because of the societal attitudes of that time. As a child, I was confined by very real barbed wire fences but as an adult I had an invisible barbed wire fence that was as sharp and deadly.”

“I was an activist but on the one issue that was so personal to me I was silent. I was closeted most of my life. I came out very late, at 68 years old, because it was torturous to see all these other people who were campaigning for equal rights and I was protecting my career, feeling guilty, feeling selfish, depending on them to do it.”

For generations of fans, Takei will always be known as Sulu. In Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991) Sulu finally captained his own ship, USS Excelsior, and returned to the role in an episode of the series Voyager in 1996.

Would he put on Sulu’s uniform again? Yes, but given the limitations of age, only if he could command from Sulu’s “magisterial seat” aboard Excelsior. And, he adds, why not make Sulu an admiral?

It is important to remember the internment 80 years ago so that it never happens again, Takei says. It is a shameful part of US history for which the government officially apologised in 1988 and paid reparations. “Knowledge is not only power, but wisdom,” he reflects. “At times of crisis, people turn hysterical and irrational. People are fallible. As noble as those ideals of democracy are, under those circumstances of war, irrational and hysterical actions result and that is why we were incarcerated.”

They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei is published in Australia by Penguin Random House.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout