NGV exhibition explores the art of looking at photographs

A PHOTOGRAPHIC exhibition drawn from the holdings of the National Gallery of Victoria, Looking at looking evokes the way we look at the world.

A PHOTOGRAPHIC exhibition drawn from the holdings of the National Gallery of Victoria, Looking at looking evokes the way we look at the world, in particular through photography and other mediating technologies such as television and video cameras, and the way we are looked at, or indeed look at ourselves.

Diverse in the kinds of images it comprises, the show is also inherently open-ended and suggestive. It is the condition of humans, as social creatures, to live in the eyes of others, and a large part of growing up, of achieving maturity, consists in knowing how to negotiate these relations. As a child we learn to look at a person when we speak to them. We are taught to bear ourselves with poise when spoken to. We are told not to stare. We learn to address others in a confident and respectful way without being cringing or overbearing.

We are encouraged to be ourselves and to maintain our own sense of integrity, rather than to be hypnotised by the eyes of our peers, staring us into conformity and often into dangerous behaviour. As we grow to adulthood we learn to dress and present ourselves in ways appropriate to the circumstances in which we are to be seen, just as we become expert at different levels and styles of speech and writing. We learn where touches of individuality or eccentricity may be appealing, rather than embarrassing.

These are essentially lessons about maintaining inner equilibrium in our interactions with those around us. Those who have not learned such lessons demonstrate this fact in their awkward, boorish, or insensitive behaviour, as well as in their physical presence, dress and bearing.

Our sense of the appropriate is so finely calibrated we are instantly aware of these failures of social ease; as for the more radical cases of mental derangement or dereliction, we can usually detect their signs in the bearing or gait of a passer-by in the street.

Some people cannot bear the effort of social interaction and constantly renewed negotiation with others, and surround themselves with the defensive shell of affectations. Such a shell may be either, in the more sophisticated cases, a mask of false impassivity or an ostensibly self-revealing display. Piercings and other self-mutilations seem to originate partly in the urge to manifest psychic wounds in an external manner, partly in the instinct to forestall inquisitive stares by putting up a monstrous barrier from which others turn away.

The crisis of obesity in the Western world can be considered in this light too, as can the corresponding condition of anorexia. These fundamental disorders of self-management and physical composure seem to be partly a symptom of moral damage and partly a barrier against intimacy. Particularly striking in the context of a world in which many lack enough food to eat and others actually starve to death, they cannot be reduced to the objective problem of the availability of junk food, marketed by irresponsible corporations to an ignorant and self-indulgent public. Nor are they simply a matter of individual neurosis.

Clearly the relatively sudden and widespread appearance of a serious psycho-physiological problem must have a social dimension, and one factor at least is no doubt the alienation of life in the modern urban world: for the past couple of centuries literature, art and cinema have dwelt on the malaise and psychological damage suffered by human beings who are obliged to live increasingly in the eyes of strangers.

The relation between people in a society of manageable size is an intersubjective one: individuals recognise each other, if not as people they actually know, at least as members of a common community, from whom they can expect recognition in return, and among whom they can share cues about how to behave.

With the breakdown of this mutuality, people are exposed to being seen as objects by others; the 19th-century phenomenon of dandyism which so interested Baudelaire among others was in reality an attempt to manage the objective image we present to others. Various sub-cultural groups since then have carried this deliberate performance of alienation much further, overtly presenting themselves as outside the mainstream of social life.

But alienation leads to narcissism, with its Janus faces of self-obsession and self-loathing, a pattern we recognise in the pairing of obesity and anorexia, or various forms of substance abuse and the ritual purgation of personal-training sessions. Can we transcend this sterile self-absorption?

Deep engagement with art and literature may at least mitigate its effects, and this is hinted at in one work in the exhibition, a large photograph by Thomas Struth, showing a group of mostly youngish visitors in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Intent on the marble sculptures before them, many of them involuntarily fall into physical attitudes that mimic those of the carved figures.

There is something moving about the way that an artistic idea formulated two and half millennia ago comes to life in the very bodies of these viewers; but it is actually an image specifically of the way we respond to sculpture, which is corporeally and kinaesthetically rather than merely visually, and more generally the way we connect with all art when we do so genuinely. For art does not present us with a complete package of meaning so much as a form or mould into which we must pour our own experience and rediscover it shaped into a perhaps unexpected pattern.

Significantly, one couple only, in the centre of the composition, is not looking at the works directly but through the viewfinder of their camera. The effect is to turn the sculptures into images and thus to cancel out any possibility of physical interaction and response; alone of the figures in the room - except for another camera-carrying woman on the right - their stances are obtusely unresponsive to the reality of the artistic ideas that surround them.

It is an ironic comment for a photographer to make on the de-realisation of the world through photographic representation, but it is a theme picked up by several other adjacent works in the exhibition, particularly ones that refer to the perception or non-perception of war through contemporary technologies of representation.

John Immig's small black-and-white photographs were taken of television screens showing news reports of the Vietnam war, including the now familiar juxtaposition of elegantly dressed newsreader in the foreground with war footage unfolding as though on a screen behind her. This was, as is often repeated, the first television war; the first that we could watch on the nightly news, and such immediacy of access to the reality of conflict is held to have fuelled anti-war sentiment within the general public.

No doubt this is true, and yet what Immig's pictures suggest, with their shadowy silhouettes of figures and events taken out of any context, is also remoteness and ambiguity. It is ultimately the Platonic conundrum of the loss of reality when images are made from other images, but we have also become, since the 70s, desensitised to the impact of photographic images of violence by their frequency but also more alert to the possibilities of manipulation.

The photographs taken in Iraq by Ashley Gilbertson are striking in the way they achieve a dispassionate view that nonetheless constantly evokes a tension between the individual looking and the one looked at. It is at the opposite extreme of the mutual recognition that constitutes the bond between members of a community. In one case, a member of a Shi'ite militia lies wounded on the ground, seen through the arms of an American soldier. In an even more striking image, a soldier, tense and alert, faces an apparently innocent glimpse of daily life seen through a gun sight whose cross-hairs frame the scene with connotations of menace.

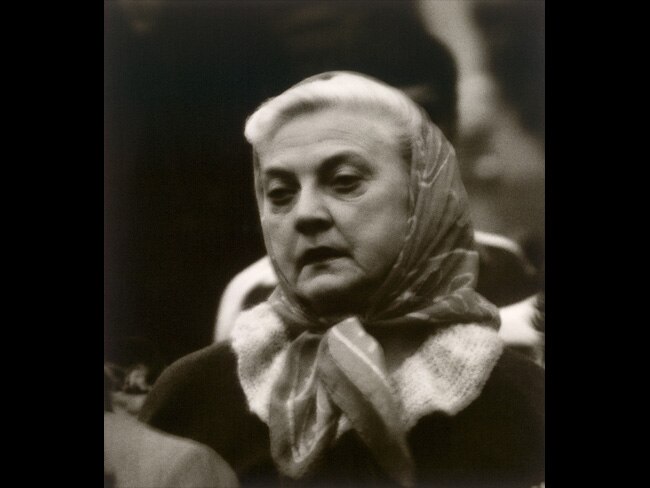

Far from the theatre of war, a number of pictures from Bill Henson's crowd scenes shot 30 years ago evoke a similar alienation. These pictures of commuter crowds in Melbourne were taken with a telephoto lens, from a considerable distance and unbeknown to their subjects, who are viewed with the same detachment as John Brack's frieze of tired and dispirited city workers in Collins St, 5pm (1955).

There is thus no mutuality between the photographer and his subjects, who are unaware of being photographed, but also and significantly, no connection between the people themselves. If we look closely, we may notice that one figure will occasionally glance at another, but it is either casually or furtively, and the gaze is not returned. These individuals are in their own worlds, and they are not a particularly happy ones: features are grim, preoccupied or just worn out.

We know that each of these faces could be animated and even lit up by a smile if they encountered a friend; but in the absence of connection and community, herded together with strangers, they sink into a kind of apathy which is never serenity.

These pictures seem to confirm that the conditions of mass existence without community produce a kind of self-enclosure which is not self-possession: there is a retreat into the self which is not a withdrawal to a solid core of identity but into a sort of blankness, exposed to transient and adventitious feeling. Identity is something that is constituted or composed in relation to structures beyond the self; it is inseparable from one's social role and the network of personal relations entailed by that role.

If identity can be imagined in solitude, it could only be in relation to some other reality that transcends the individual, as we glimpsed in Struth's photograph, through the great works of art and literature and music of the past which embody an understanding of the world crystallised in enduring form by minds long extinguished. Or it could be imagined in the mystic's communion with the divine.

In practice, identity is woven from many strands - of the relations with our fellow human beings shaped by our roles in society as parent, friend, teacher, manager, and so forth, as well of the connections we have with distinguished minds of the past and with religious experience. No one is entirely without these supporting structures, but many people live with an impoverished and fractured social structure, without the resources of culture or religion.

This kind of vacancy is evoked in one of the few Henson pictures of a single figure. It is a boy looking straight towards the camera, although perhaps not at it. His gaze does not imply connection with the eye behind the lens, but his evident consternation implies the sudden discovery of an abyss. It is not so much the camera he is looking at, we may surmise, but the mirror, and the object of his appalled gaze is his own image.

Looking at looking: The Photographic Gaze

NGV International, Melbourne, to March 4