How Yayoi Kusama conquered the art world from the confines of a psychiatric facility

Yayoi Kusama, who voluntarily checked into hospital in 1973 and never left, has never been more popular. To witness her work is to unravel a 95-year-old mystery – but what’s with her obsession with pumpkins? | Listen to the weekend edition of The Front.

There is a giant pumpkin perched on a pier on the island of Naoshima, in southern Japan. It’s yellow and black, and at noon on this brilliant September Saturday its polka-dot reflection dances off the cerulean Seto Inland Sea.

Art lovers, families and influencers mill around the giant squash and take selfies or pose for pictures. A tour guide carefully arranges a gaggle of subjects around this art island’s most famous work. Once content, he points a camera at the group and calls out “Hai, chiizu”.

OK, cheese.

A woman sticks her head out from beneath a parasol and shakes her head. Chiizu won’t do.

She shoots a peace sign to the sky and yells “Kusama.”

Snap.

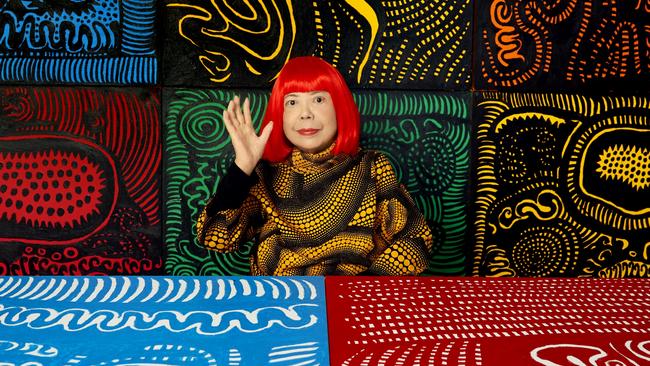

Kusama would, of course, be Yayoi Kusama. She the prolific progenitor of pumpkins and of the global acclaim. She of the decades spent in a mental facility and of the 95 years of age. She of the luminous red bob and of the polka dots. She of the otherworldly, dinner-plate eyes. She, the queen of the international art market.

That Kusama.

Indeed the nonagenarian artist and sculptor, who voluntarily checked into a Tokyo psychiatric hospital in 1973 and never left, has never been more popular.

Last year she was the world’s highest selling artist, beating out other leading contemporaries David Hockney and Yoshitomo Nara, with her work netting more than $80m, according to a report by data analysts Hiscox.

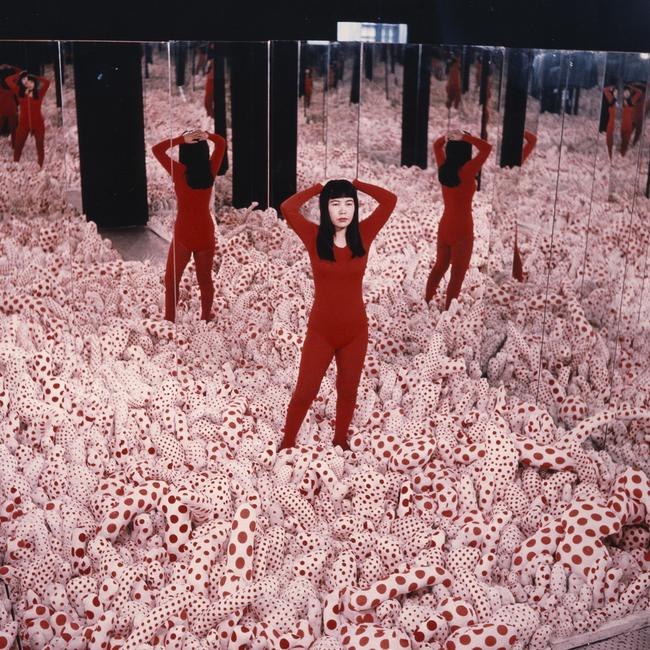

The Japanese artist is a ubiquitous presence in major galleries around the world. From her large-scale mirrored Infinity Rooms and dotted net paintings to the pock-smattered rooms she calls obliteration spaces, her tactile soft sculptures and trademark multi-coloured pumpkins, Kusama’s art has become the most in-demand work on the international commercial market.

That success has not been harmed, either, by the fact she arguably is the most Instagrammable artist on the planet. Her sellout shows at major galleries around the world are invariably complemented by a deluge of social media posts. As a senior Australian art figure once sardonically remarked to this writer: “If you view a Kusama work and don’t pose for a selfie, were you really there?”

Her paintings, installations and sculptures are held in many major Australian institutions and private collections. There have been exhibits of her work on these shores in recent years – at Brisbane’s QAGOMA and Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art – but the National Gallery of Victoria has gone all out.

From December 15, more than 200 works – paintings, sculpture, installation, video and collage – will be displayed across the ground floor of the St Kilda Road gallery in the largest retrospective of her work seen in Australia.

The exhibition will extend beyond the gallery walls, outside into the adjacent emerging $1.7bn Melbourne Arts Precinct, that will eventually become home to The Fox, the NGV’s contemporary art museum slated to open in 2028.

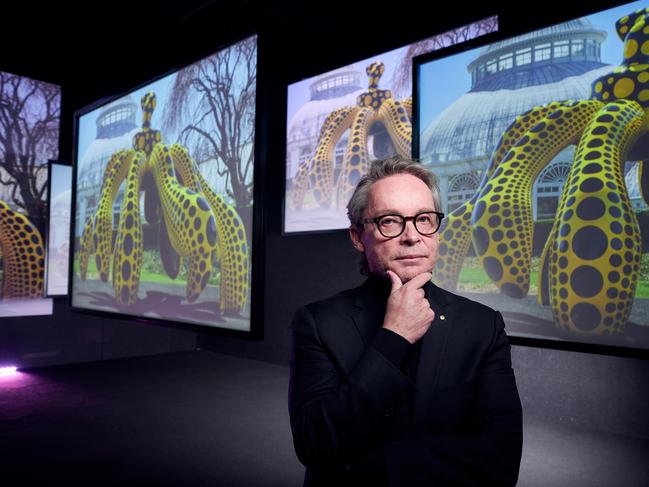

NGV director Tony Ellwood has described the upcoming exhibition as “profound”. But what does Kusama have to say about it?

Well, not much. The artist no longer does press interviews. At least, not officially.

Occasionally she will offer a sound bite to a reporter or documentary crew. Largely, say those who know her, she likes to concentrate on her work and her health.

The artist keeps a close, familiar band of confidantes. She has no family of which to speak. The closest thing, perhaps, to a living loved one is a fellow giant of the Japanese cultural world, Akira Tatehata.

“Kusama is a complicated person. And she is a very important artist,” says the internationally acclaimed poet and former director of the National Museum of Art. “There is no one like her.”

Tatehata is speaking to Review in the offices of the Yayoi Kusama museum, a five-storey architecturally designed building in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. The institution – replete with red-spotted mirrored lifts and a giant pumpkin sculpture on the rooftop – is closed today and in the process of changing over exhibitions.

Tatehata is a regular visitor here, and to the woman to whom it is dedicated. Indeed, he has been arguably Kusama’s greatest professional, if not personal, support for more than a half-century.

He has since their first meeting in 1973 variously championed her as a rising star of modern art, chosen her as Japan’s representative at the Venice Bienniale and promoted her work internationally. He likes to think of himself, however, as simply a good friend – someone privileged to know the “real Kusama”.

“She is supported by so many people – from her nurses in hospital to her many fans around the world, but she doesn’t have any family,” he says. “Kusama is actually a very lonely person, despite there being so many people around her.”

The seeds of that disconnect, Tatehata says, were planted early in her life in mountainous Matsumoto, the town in provincial Nagano where Kusama was born and raised.

■ ■ ■

Yayoi Kusama was born on March 22, 1929. The youngest of four children, her middle-class family owned a commercially successful seed farm and plant nursery. She began drawing from the age of 10, around the same time she began experiencing hallucinations – visions of dots and flowers that would haunt her waking hours. Kusama ultimately developed a fear the dots would consume her and that eventually they would cause her to “self-obliterate”.

Says the artist in the 2018 documentary KUSAMA: “My art has always originated from hallucinations only I can see. I translate the hallucinations and obsessional images that plague me into sculptures and paintings.”

Her parents did not support her creative endeavours, despite the calming effect on her mind, and her mother would destroy her artwork and reportedly was physically abusive. Her father’s extramarital activities engendered in her a lifelong fear of sex and a contempt for and fear of the male genitalia.

As she told the Financial Times in 2017: “I don’t like sex. I had an obsession with sex. When I was a child, my father had lovers and I experienced seeing him. My mother sent me to spy on him. I didn’t want to have sex with anyone for years … The sexual obsession and fear of sex sit side by side in me.”

By the time Kusama was 13, World War II was in full swing across Europe and the Pacific, and she was sent to work sewing parachutes in a browned-out military factory, with the ever-present threat of Allied bombers flying overhead.

After the war, Kusama studied Niohonga painting in Kyoto before shifting her focus to the American art world. She came across the work of celebrated painter Georgia O’Keefe, and eventually the pair began a dialogue via mail. O’Keefe encouraged the young Japanese artist, who shared an affinity for environmental landscapes, to follow her instincts and take her art to America. In 1957, Kusama left Japan and landed in New York, with a suitcase full of paintings and a promise to herself – that one day she would conquer the international art world.

■ ■ ■

The ferry to Naoshima from the port town of Takematsu takes about an hour. The boat gently wends its way through the Seto Inland Sea and its many densely forested islands – there are almost 3000 in this body of water – before a bright red-and-black blob appears on the horizon. It can only be a Kusama. Red Pumpkin, a 2019 work, is a sentinel at the tip of the island. The gleaming work stands in stark contrast to a nearby colony of rusting machinery and rigging, monuments to this island’s long industrial history.

For more than a half-century, Naoshima was a key part of Japan’s copper industry. Mines and smelters were its stock in trade until devastating environmental damage on Naoshima in the 1980s saw the most unlikely of interventions – a privately funded philanthropic transformation of the island, led by billionaire Soichiro Fukutake and internationally celebrated architect Tadao Ando.

The architect, with the backing of Fukutake, would design the island’s sprawling Benessee House Museum, and its associated Valley gallery nestled into an adjacent mountain; the subterranean Chichu Art Museum – a series of galleries lit via geometric openings punched in the earth’s surface – and the Lee Ufan Museum, a concrete bunker and outdoor garden that overlooks the sea.

It’s clear, though, as the ferry moors alongside Red Pumpkin and people rush to disembark and inspect it, that this island is all about Kusama. The landform, dotted with sculptures and artworks, is just 15sq km in area but its elevations (up to 130m) are not to be underestimated. Some art lovers choose to saunter its length and breadth. The smart ones take an e-bike, hired from a local vendor for the day (Review’s is a red number, complete with polka-dot duco and small basket on the front).

Just past the Chichu, which is showing a world-class James Tyrrell light installation and a Monet triptych the size of a small football field, is the turn-off to the Benessee. Cyclists are ordered to dismount and walk, and as we round the first heavily forested bend into the valley, sunlight can be seen bouncing off a sea of reflective surfaces. Soon enough, the entire apparition materialises – Kusama’s Narcissus Garden, 1400 gleaming steel balls. They spill up and down the stairs of the Ando-designed brutalist Valley Gallery bunker, down the hill and into a large pond, where they jostle loudly with each other.

A new iteration of the work has recently been acquired by the NGV, and will be placed around the waterfall at the NGV’s entrance. Ellwood says that purchase – made at the same time the gallery acquired a rare Kusama Dancing Pumpkin, an 11-legged, nine-tonne sculpture, unveiled earlier this month – is a coup for Victoria.

“(These works) will leave a defining impact on the NGV Collection and will be available for all Victorians to enjoy for many years to come,” he says.

The two works are the latest in a series of major contemporary art acquisitions (works by Thomas Price and David Shrigley, among them) made by the NGV in what is widely seen as a bolstering of stock ahead of the Fox’s opening in four years’ time.

While Tatehata acknowledges the 2020 work Dancing Pumpkin, one of only two such works to have been shown anywhere in the world, he says Narcissus Garden is a critical work in Kusama’s career.

At the 1966 Venice Biennale, the Japanese artist exhibited it in the Giardini, placing the 1400 silver balls along with a sign reading “Your narcissism for sale” on a lawn adjacent to the Italian pavilion. There was only one small issue: she hadn’t been invited.

Kusama’s guerrilla exhibition, during which she sold many of the spheres for 1200 lira each (the equivalent of $2), was shut down by authorities and caused a small sensation in the art world.

The stunt may have been a commentary on Kusama’s disillusionment with the art world, but it was also a sign of her desperation to be part of it, says Tatehata.

”She was a female artist at a very male-dominated time,” he says. “It was very hard for her.”

The work was ironic, too, in its way, Tatehata says, given Kusama is an ego-driven artist.

“She loves herself,” he says, laughing. “She’s very narcissistic. But she also is very charming.”

The silver balls are still clanging loudly as a small horde of gallerygoers traipses down to the beach, around the bend and up to the main Benessee House Museum. Its 180 degree views of the island, to say nothing of the world-class art inside, are worth the price of perspiration. At the museum’s entrance, an exhausted trundler beseeches the concierge. “The pumpkin. Where can I find the yellow pumpkin?”

■ ■ ■

“Seeing the big city, I promised myself that one day I would conquer New York and make my name in the art world.” So quoth Kusama, in 2018, of her first day in New York.

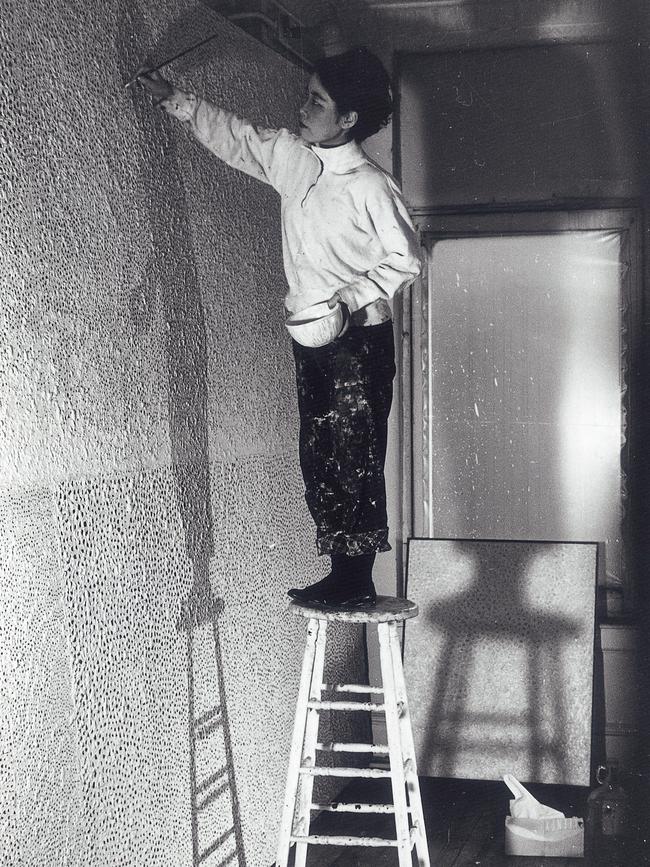

After arriving in the US in the late 1950s, Kusama enjoyed some early success in New York with her net paintings and soft sculptures – a practice inspired by her experience working with fabric in the munitions factory. She called these works “accumulations” – variously couches and rowboats covered in plush, plenteous phalluses.

She made her first infinity room in 1965, turning to mirrors to explore deeper her obsessions with death and infinity, and embraced the anti-war movement and its accompanying naked protests at the height of the swinging ’60s. Despite her apparent abstinence, she embraced the free-love philosophy, and established the Church of Self-Obliteration. She appointed herself the “High Priestess of Polka Dots” and in 1969 officiated over what is thought to have been the first gay marriage in the US.

But despite showing alongside some of the avante garde’s biggest names at the time – Andy Warhol, Donald Judd, Claes Oldenburg, Jackson Pollock – Kusama felt as though her gender and ethnicity were holding her back. She would go on to complain her work had been plagiarised and copied by her contemporaries. Her response was to work obsessively.

“Eventually,” she said of the US experience, “I became ill. I had painted too much.”

By the early 70s, after a suicide attempt and with her mental health in decline, Kusama returned to Japan, where she was either an unknown quantity or seen as diametrically opposed to the prevailing conservative ideologies of a nation still emerging from the long shadow of World War II.

“She was known as the Scandal Queen,” Tatehata says, with a smile. “I was scared of her.”

Tatehata at that time was a young curator at the NMA, where he would later rise to the position of director.

“I didn’t have much power then but I knew she transcended the pop-art kitsch scene and I was irritated her art was misunderstood. I believed she needed to be better recognised in Japan,” he says.

So began a professional and personal platonic relationship that exists to today. Tatehata would organise and stage exhibitions of her work in Japan, and as Kusama’s late career began to take off following a retrospective in New York in the late 80s, he was never far away. In 1993, as commissioner of the Japanese pavilion for the Venice Biennale, Tatehata broke with convention of having three representative artists at world’s most prestigious art jamboree. There would be only one.

“At the time I had a free hand to decide who the artist would be, and when I mentioned Kusama was living in the mental hospital, (the government) said it was too dangerous a choice. But the deal had already been done. Kusama had been chosen.”

The exhibition was critically acclaimed.

This is not to say, of course, that Kusama is a favourite of the critics. Her work has throughout her career been criticised as being “fizzy”, “bubbly” and lacking depth of meaning. In 2018 in The Guardian, British art critic Jonathan Jones derided Kusama’s work as being “as artistic as a lava lamp”.

Tatehata says he has always believed in her artistic skill.

“Her work is so beautiful.” he says. “Compared to Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko, she is a far better painter – a far better quality artist.”

But what of the paradox in Kusama’s work: how such apparently joyous work comes from such a clearly troubled place?

“Her obsessions are everything. There is the obsession with death (which) has been with her (for her) entire life, but it’s not just death. Obsession is an obsession. So because of that, she will never be tired of the theme of repetition, and she will never abandon it. The obsessions she fears the most are actually, ironically, what motivates her to make her work.”

In 2009, in a newspaper interview, Kusama opened up about her process: “I fight pain, anxiety and fear every day, and the only method I have found that relieves my illness is to keep creating art. People call me crazy, but I am not crazy. My vision is clear in my madness.”

■ ■ ■

Punch in the hashtag #YayoiKusama into Instagram and it will yield more than a million mentions. A further 300,000 posts are dedicated to #YayoiKusamaExhibition and #YayoiKusamArt. Each time a major exhibition is staged, social media floods with “look where I am” posts. She has latterly become a fashion icon, too, having started her own fashion label, and collaborated with Louis Vuitton, Marc Jacobs and Lancome, among other high-end fashion brands. Despite her quiet life, she is considered a national treasure in Japan and has been awarded the Order of Culture and the prestigious Praemium Imperiale world culture prize.

If further proof were needed of her global influence, there even are two cryptocurrencies named for her: Kusama Coin (I KSM is $US21.70) or Polkadot Coin (I DOT $US5.1). The artist has no affiliation with either, according to her gallery.

So widespread is the Kusama Effect that in 2017 The Atlantic ran an article by Sarah Box under the title An Artist for the Instagram Age asking whether Kusama’s work was really about “seeking profound experiences through art or posting selfies?” Staging a Kusama show, wrote Box, was akin to having the circus come to town. Ellwood, no doubt, will be hoping for record numbers through the gallery’s doors over the exhibition’s four-month run.

While Kusama’s gallerist Hidenori Ota, founder of Ota Fine Arts, concedes Instagram has played a part in the artist’s late career renaissance, he says her work goes far beyond the interfaces of TikTok, Facebook and Instagram.

“The element of Kusama’s popularity has many levels. That (social media) is certainly a part of her success. But really there is such power in the colour and the expression of Kusama’s art,” he says. So in demand is she in 2024, he adds, the Kusama museum is being overwhelmed with requests to show her work.

“She is unlike any other artist: her practice is quite varied. It’s contemporary, yes, but it’s also very historical. That’s quite rare. I hope people find the depth of heart and philosophy in her work.”

Ota says the key to Kusama’s success has been self-belief. “From the beginning, she knew she would conquer the art world. She believed it. She never gave up, and she never will. She is always searching for more recognition.”

Ota speaks with Kusama every second day and is always ready to jump whenever she needs to see him. “I’m like a soldier,” he says, laughing and mock-saluting. “I will see her as often as she needs to see me, depending on her physical status.”

Ota reveals Kusama, who “works every morning from 8am and 9am”, is working on a new style.

“She has begun making small-scale portraits – portraits: drawings and paintings. Some of them are self-portraits, and we don’t know at this stage who the other faces are. But this is certainly a new way of working for her. It’s very interesting,”

The artist has, from a young age, been obsessed with death. Is it a theme she increasingly contemplates now she is 95?

“She has not changed much,” Ota says. “She has her obsessionist behaviours, and they rarely shift. That has been her life.”

There has been one major shift, however. Since the pandemic, Kusama rarely works in the studio, and instead makes art from a second room in her ward. “It is a good space for her,” Ota says. “She can paint and mould (pumpkins from clay), and she can write her poetry. Kusama always is working. It is her life.”

■ ■ ■

So what’s the deal with Kusama and pumpkins? The obsession began, says Tatehata, in the family nursery. One of the first things she ever drew was a pumpkin; she won an art prize for the work when she was 11.

But the artist has said the vegetable represents for her stability and modesty, things that have to her never come naturally. Ota says the pumpkin works are the most popular among collectors, especially in the Asian market. (Its many seeds and regenerative qualities align with the philosophies of Buddhism, he says.)

Descending the stairs at Bennessee, Kusama’s most famous work – simply titled Pumpkin – is hard to miss. It sits conspicuously on a concrete jetty stretching out into Naoshima’s Gotanji Beach.

It was unveiled in September 1994, and remained there, unmoved, until August 2021 when Typhoon Lupit dislodged it from its foundations. The tempest tossed the giant gourd into the sea. Flaccid and broken, it washed up on the shore the following day like some exotic sea urchin.

“It was heavily damaged,” says Ota, “so Kusama and the team set out to make a new one..”

The process took almost a year, and in October 2022, the re-creation was unveiled.

“It is a very important work to Kusama, because it was her first permanent outdoor sculpture,” Ota adds. “She has a great affinity (with it).”

As Review waits its turn to inspect the work, a young couple – all duckfaces and smartphones – enters its orbit. The queue of excitables shuffles forward. They’re all here for the same thing: to bear witness to the interchangeable nature of Kusama and her art. To unravel a 95-year-old mystery – this paradox wrapped in a pumpkin – of resilience forged through fragility. To complete one of the great artistic pilgrimages, here at the edge of the world.

Or maybe they’re all just here for the likes. The artist probably wouldn’t blame them.

Yayoi Kusama runs at the National Gallery of Victoria from December 15 to April 25, 2025.

On Kusama’s home turf, Travel - Page 7

Tim Douglas travelled to Naoshima from Tokyo with the assistance of the National Gallery of Victoria.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout