I alluded to this in my comments on the Archibald finalists recently. The reason that the exhibition is so ugly and disparate is not an oversight, but a deliberate choice by those responsible for the selection, in this case the Trustees of the Art Gallery of NSW. With 1068 applicants this year, there was no need to include the incompetent, the freakish and the blatantly commercial; but that is clearly what they wanted – a wildly uneven exhibition that would elicit a range of intense but superficial reactions: surprise, disbelief or revulsion.

The Wynne and Sulman are no better, and indeed have long fallen into such a state of dereliction that it is only worth mentioning them in order to ponder what has gone so badly wrong with the public administration of art in the last few decades.

The Wynne Prize is meant to be for landscape and sculpture but the Gallery has long given up on the criteria for the genre of landscape, just as it has given up on the requirement that portraits should be painted from life. Abstract pictures have turned up in the Wynne for years, and more recently the exhibition has been dominated, as it is this year, by Aboriginal painting. These works may refer to particular places, but in a way that is more akin to a map than to a landscape.

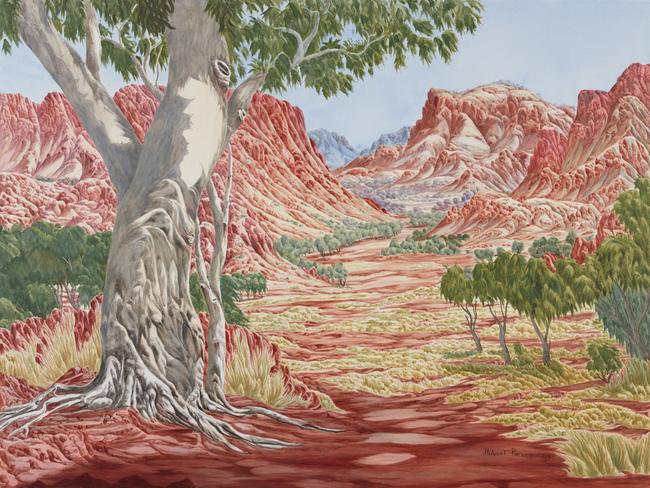

Oddly enough, one of the few pictures this year to have some feeling for the genre of landscape is by an Aboriginal artist painting in the European idiom first practised by Albert Namatjira: Hubert Parertjoula’s Tjoritja (West MacDonnell Ranges) and this is also the work that ended up being awarded the prize. The best landscape in the exhibition, however, is probably Lucy Culliton’s view of a river, Gunningrah (Bottom Bullock); this is one of the only works to have what we most look for in landscape, which is a sense of connection with and response to the life of nature in a place.

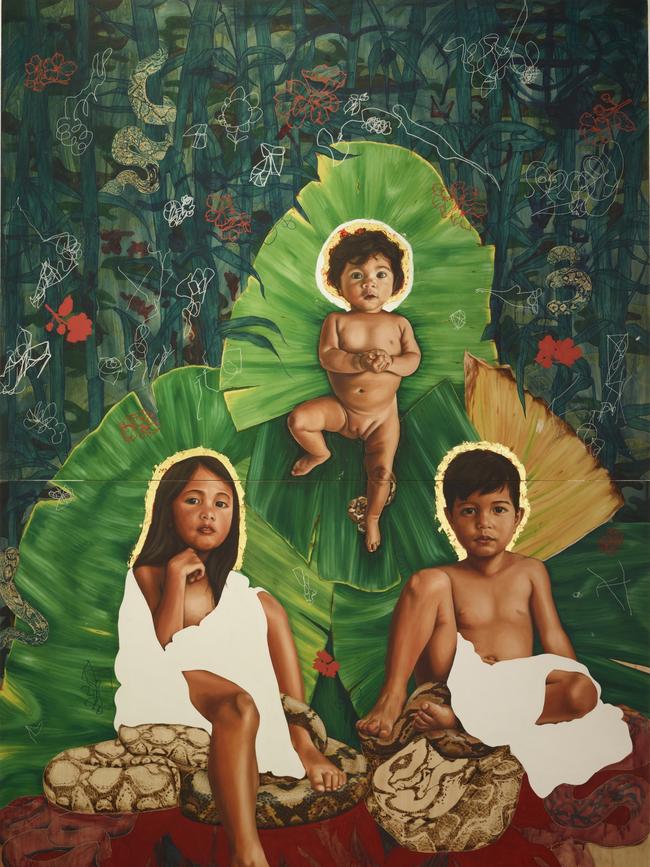

The Sulman is meant to be for subject pictures but there is no evidence here of any understanding of the genre, or of anything that could be called a subject or story. There are several pictures which could equally well be hung in the Wynne. The prize was awarded to a picture which would have been more suited to the Archibald, since it was a group portrait, although that description is too generous for what was little more than a collage of three photographic likenesses set against some tropical greenery.

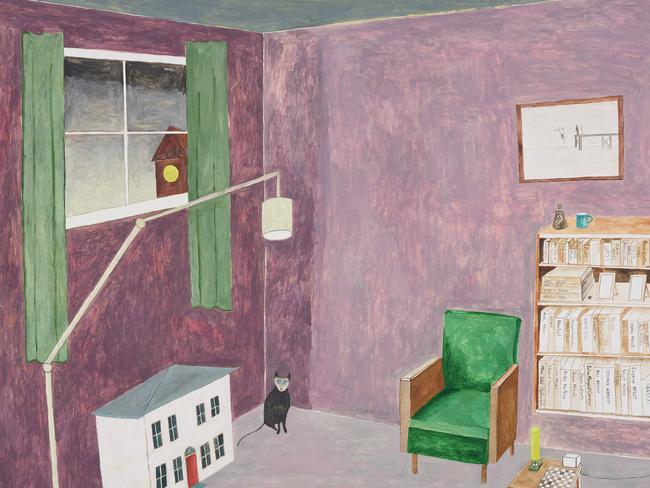

In general the implication of the hanging is that it would be intolerably naive to attempt any kind of recognisable subject picture, although one might have thought that the social circumstances of our time offered a range of possible human experience. Instead the only stance deemed acceptable is a smug, ungenerous and lazy flippancy which avoids any real moral or political content. One of the few pieces worthy of attention is Noel McKenna’s characteristically quirky Audrey and Decimus.

Painting, or at least the painting that is shown in public galleries and prize exhibitions, is in a very bad state. There may be many reasons for this, and deeper questions that I will discuss on another occasion; but it is undeniable that painting has become much more broken-down and dysfunctional than any other art form.

It is easy to see the difference if we try to imagine a similar state of affairs in music: no-one gets anywhere in classical, jazz or even pop music without technical mastery of their instruments. High standards of professional competence are expected in everything from performance to recording.

Or think of cinema: everyone understands that high standards are required in every part of a complex process that involves dozens of people each doing their job with expertise. A cameraman, a sound engineer, an editor who is not highly proficient will not even be employed; competition is intense and levels of skill are correspondingly high.

The supreme irony is that even in new and relatively new art forms such as video and digital media technical standards are high. Mastery of hardware and software is taken for granted, and high standards of execution are expected. Why then have painting and drawing, almost alone, suffered a collapse in the levels of ability and competence expected of a professional practitioner? And why is it that the worst and most incompetent are so often chosen and exhibited by the art establishment, while many who are trying to do something better are ignored?

Whatever the ultimate answer to these questions, at a practical level public galleries have a duty to foster standards and to support the best work. One of the reasons this is important is that the general public expects to find such standards represented in official collections. And what is really harmful about this trio of disastrous exhibitions is that the general public, or many of them at least, calibrate their own judgment against what they see exhibited.

They naturally assume that the Archibald Prize represents the range of what is acceptable and even outstanding in the contemporary practice of portraiture, when in fact only a handful of the finalists would be seriously considered by anyone intending to commission a portrait. Most of the pictures, in other words, fail to do what is expected of a portrait by anyone who actually wants a portrait; but Archibald portraits, as I observed long ago, are a kind of mutant variant of the genre and have evolved in a very particular and otherwise toxic environment.

As for the question of skill or technical mastery, it should require no vindication, and in fact doesn’t, as we have seen in every other field of artistic activity. But the mastery of a medium is not desirable only because we prefer work that is well made. Ultimately, it is more important in relation to process than to product; the well-made object is a by-product of expert practice.

And the reason that process is so important is that it is what allows us not only to express, but even to conceive and imagine aesthetic meaning. No one can write poetry without being steeped in literature, or compose music without a profound musical culture. In other words, we develop the ability to say something with an art form, or even to have anything to say, by learning its practice.

I have watched this with students for many years, and it is always the same pattern. Most beginners have nothing to say, or perhaps they think that they have some kind of moral or social issue that they feel strongly about, but such concerns in themselves are irrelevant and cannot be articulated in any way until the individual has mastered the practice of an art form. A passionate concern for the natural environment, for example, may be ultimately expressible through landscape, but only after submitting to the discipline of painting and assimilating the conventions of the genre of landscape.

The point is particularly clear with those material forms that require us to learn a completely new and unfamiliar set of skills, like printmaking, wheel-throwing or sculpture. Most of us, for example, have never thrown a pot on the wheel. It is a completely new and often exhilarating experience on our first attempt; it is hard, but as we begin to understand how to do it, a whole new world of aesthetic experience opens up to us.

What is particularly fascinating is the way that different individuals respond to different processes. The potter’s wheel appeals to those who are drawn in by its hypnotic movement, who love the unique combination of materiality and refinement, the wordless and almost inexplicable quest for elegant and economical form.

Printmaking, as I first saw many years ago at the National Art School, often appeals to students of a more systematic and analytical bent, and especially to those who may be put off by or floundering in the shapelessness of painting instruction today. Learning to handle the etching tools, the copper plates, the acid baths, the inking and wiping and printing gradually leads to finding something to say with these processes; Roger Kemp himself only found his way as a painter after spending time as a printmaker.

Sculpture represents an even more intense engagement with material, whether in carving wood or stone, modelling clay, casting bronze or welding metal: and there is no doubt that some artistic temperaments find themselves in this much more physical and corporeal process. There are sculptors who are also fine draughtsmen, but I have seen students with no natural flair for drawing discover an impressive talent after coming to terms with the sheer inertia and weight of sculptural practice.

This is why the basis of art teaching at any level, from primary school to tertiary, should be the inculcation of disciplines and studio practice, because this is the only thing that will release the so-called creativity that teachers think they are encouraging by unstructured teaching. Creativity is not something that can be directly taught; like originality, it only arises from the mastery of discipline.

Of course this leaves us with a question which has by now only become more unfathomable: why is painting in such a state of dereliction? Is it because it is assumed to be a naturally available form of expression, or something that we have assimilated since infancy like language?

In reality painting is as at least as technical, as complex and as subtle as any of the art forms I have just been talking about. It is not a practice that can be approached confidently without teaching, and it certainly cannot be mastered without expert guidance, both in its many strictly technical aspects, and in the history and conventions of its genres, which, as in any system of meaning, can only be varied to create new meanings when they are fully understood.

The state of prizes like the ones we are discussing directly reflects a failure to understand any of these principles, unless we are to attribute it merely to a cynical marketing instinct. And this failure pervades the field of contemporary art, which has become something like a cult, in which everyone agrees to believe the same things, however manifestly false they appear to those outside.

Indeed the dynamic of a cult requires the group’s beliefs to diverge from those of the community at large; but converts and initiates are rewarded with a mirage of the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman prizes as an Ali Baba’s cave of aesthetic treasures.

A strange disease has infected art prizes of almost all categories in Australia, like those fungal blights and parasitic invasions that unaccountably cause rows of old trees in parks to wither and die. And that disease is not simply a failure of judgment, but a perverse attraction to bad judgment.