How NZ photographer Yvonne Todd found ‘retribution by proxy’

When Yvonne Todd spotted an ex-boyfriend from a toxic relationship in the supermarket she asked her husband to help her exact a surprising act of revenge.

“It’s a long story,” begins New Zealand photographer Yvonne Todd. “I had this boyfriend when I was a teenager. I saw him in my local supermarket and hadn’t seen him for 33 years. I knew who it was. I could tell by his tattoos. And I was really triggered because it was a very toxic relationship. I decided I needed some sort of closure. So I turned my husband into my feelings for this ex-boyfriend by making him a figure of, I don’t know, it’s not humiliation, but there’s something ludicrous about this character.”

The character to which she refers is wearing a shift dress, a long silvery wig, brown stockings and red rollerskates. As with most of Todd’s portraits there’s some thing off-kilter, amusing and absurd about this work, titled Ice Blue.

“I consider it to be an image about retribution, but by proxy because I’ve actually used someone I love as a stand-in for this boyfriend I had in 1989.”

She reflects: “The problem with me is I carry things with me and they find their way into my work, but a lot of time can lapse.”

Todd is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated contemporary artists and will soon make her way to Victoria for the Ballarat International Foto Biennale as one of the headliners for the 10th iteration of the festival, opening this weekend. The 50-year-old photographer is renowned for her glamorous portraits, which combine the highly stylised allure of glossy fashion magazines with disruptive and often humorous props or accessories: a wig, false teeth, a wizard’s hat – or in her husband’s case, a pair of red rollerskates.

When she won New Zealand’s most prestigious art prize, one of the judges, Harald Szeemann, famously said Todd’s entry was “the work that irritated me the most”. The win, which catapulted Todd’s career, was announced by the New Zealand Herald thus: “A (29)-year-old Auckland photographer who used to moonlight as a wedding photographer and waitress at strip joint Showgirls has tonight won the inaugural $50,000 Walters Prize for contemporary art.”

Yes, Todd also worked at a strip club when she was aged 23 for six months after spending two years studying photography. Did the fact make people even more intrigued by her work?

“I guess the convergence of wedding photography and strip club hostessing will always be one of the defining curiosities of my CV,” she says. “One that I can’t seem to escape.”

The artist is speaking from her home office/studio on Auckland’s north shore. It’s nice and quiet, she says, because her three young sons are watching TV in the other room. Hers is a demeanour of astute self-awareness and self-deprecating humour; in an industry brimming with the muddle of artspeak, she is refreshingly down to earth.

“I think my work is quite funny, not in a really overtly way,” Todd muses. “But there’s low level humour and oddity sort of oscillating through the images. I feel compelled to create portraits that have some sort of interesting and original aspect to costume. The process of creating the character is probably more important than the taking of the photo.

“I guess I’m more socialising the subject and what they’re wearing, but it’s coming up with the ideas around the clothing, the pose, the objects they might be holding. And there’s an awkwardness to them. I think that just reflects the awkwardness I feel as a human navigating the world.”

Ballarat will show works from Todd’s series The Stephanie Collection, including Eggself, a portrait of “a feminine Nosferatu character skulking along with her macrame egg-holders”. It could easily belong to a glossy fashion magazine – but then there are the eggs.

“I made that when I just found out the week earlier I was going to have twins. So my headspace was quite scrambled,” Todd says with a laugh. “I never thought I’d be a person who would have twins. In some ways I was in denial about what I knew was on the horizon. And I just kept making art and living in this creative space knowing that soon my life would be very different.”

As she approached her due date she shot the video Strontium, named after the heavy earth metal. It is of a woman dressed in a deep purple jumpsuit and reflects the physical awkwardness Todd was feeling.

“I was very cumbersome at the time. There’s this minimal activity, but (the subject’s) kind of just moving, staring at the camera. It’s almost like a marionette type. Often I don’t question (what I’m making). I just make things and then they make sense years later.”

Todd knew from a young age she wanted to be a photographer. As a child she was fascinated by the feminine appearance; she found American beauty pageants on television “hypnotic” and “fetishised” the woman who worked behind the beauty counter at the local chemist.

“That was my only kind of interaction I had with women with quite a lot of makeup on,” she says. “I did a whole series on beauty consultants about 20 years ago, which had a direct connection with this childhood obsession.”

She was envious of her cousin who won drawing competitions, and was eager to find her own form of expression. For her eighth birthday she was gifted her first camera and started taking photos, but realised she would need some training if her images were to resemble the ones in magazines.

After doing a bachelor of fine arts at the university of Auckland she further honed her practice while working as a wedding photographer. Wrangling “sometimes 100s of people”, she jokes, was so emotionally fraught it would make for a brilliant TV series.

“What I found really interesting was the family dynamics,” she says. “You’d have divorced parents who hadn’t spoken in 15 years. You had to bring them together for photos and they despised each other – things like that.

“Weddings were really good training because they’re high pressure. And you have to be attuned to moments. It’s not particularly prestigious in a contemporary art sense but for me it was a useful experience.”

Today she is represented in most Australian state galleries, with the largest collections of her work held by the The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Auckland Art Gallery. From the moment Todd arrived on the scene, her photographs made an impact on the New Zealand art landscape, says Auckland Art Gallery senior curator of global contemporary art Natasha Conland.

“Cleverly merging the trickery and language of commercial photography with popular genres of portraiture she created a commentary on plasticity in contemporary culture,” Conland says. “Her female characters and their overt camp looked like they were emerging from pages of Mills & Boon or 1980s teen fiction Sweet Valley High.”

Vanessa Gerrans, CEO of Ballarat International Foto Biennale, says Todd’s work was in step with the theme of this year’s festival, “the real thing” – in part a reflection on the changing nature of photography in the face of AI – because there “is a deceptive allure to her portraiture”. “The portraits are beautiful and glossy but what attracts me to them is they’re slightly unsettling nature that makes you want to reflect.” Similar feelings can be stirred by AI photography, or “promptography”, Gerrans says, which audiences will have a chance to experience as part of the festival for the first time as it unveils a dedicated prize for AI-generated imagery.

One of the judges is German artist-photographer Boris Eldagsen, who was involved in a stoush with The World Photography Organisation earlier this year when he mischievously entered and won the creative open category of the Sony World Photography Awards with his AI-generated photo – only to turn around and refuse the prize. On his website he wrote that he applied as a “cheeky monkey” to spark a debate about the contemporary definition of photography and whether it had space for AI.

The welcoming of controversial technology is a useful point of reflection for the Biennale, which was first held in 2005, five years before Instagram turbocharged popular selfie culture. Biennale founder Jeff Moorfoot has been invited back to curate an exhibition featuring the work by 15 regional artists responding to “the real thing”. And alongside Todd the other headliner is surrealist Swedish photographer Erik Johansson who manipulates his images to create optical illusions.

Todd, on the other hand, does minimal (if any) retouching on her images. Back in her studio, her art is created in frenzied bursts when she’s not parenting three boys and working as a high school art teacher. Models for the shoots are booked via talent agencies – “I’m not the kind of person who accosts strangers in the street” – and given a detailed brief, so they know to bring along their sense of humour to what could potentially result in an unflattering photo.

Todd’s mother, a retired accountant, is her very supportive “unpaid manager” and makes a lot of the costumes for the shoots.

Still, even with the dream team, things don’t always go to plan.

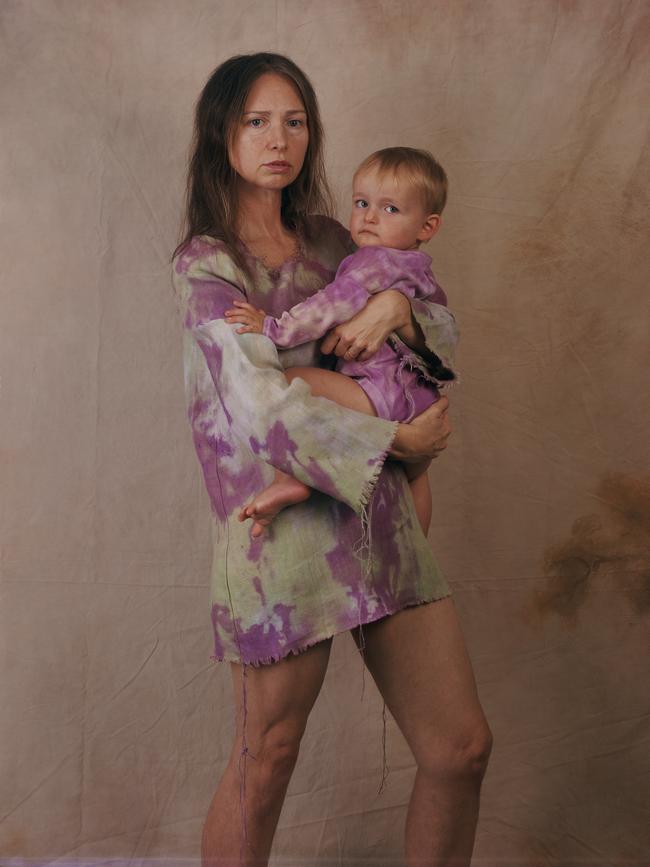

“I did a shoot a couple of years ago with my husband dressed as a long-haired Jesus character in a pink smock, holding one of the twins who was a baby and was crying. I was trying to take the photos and it was really traumatic for everyone. After the shoot I found my mum lying on my oldest son’s bed crying. I felt bad after that, that I put her through this really harrowing experience,” Todd says, before adding in a deadpan manner, “ – but I did get the shot.”

Ballarat International Foto Biennale is held in Victoria and runs August 26 to October 22.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout