Hey, true Bluey: the heart that drives Australia’s top kid’s TV show

How family of cartoon blue heelers created in Brisbane a became a global television sensation.

The nation’s favourite children’s program stars a family of blue heelers and, other than the fact that they can walk on their hind legs and talk, they’re not particularly remarkable. They’re just four dogs getting on with their lives while living in the suburbs of a cartoon city that looks very much like Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

For sisters Bluey and Bingo — aged six and four respectively — their young worlds are full of wonder, curiosity, uncertainty and humour as they learn to navigate the complex web of social interactions and emotionality that surrounds them at all times, even inside their own home, and especially inside their own heads.

For parents Bandit and Chilli, their days are driven by the relentless flow of joy, exasperation, tedium and heart-melting moments of tenderness familiar to all parents. Their lives, too, are a tangled web of commitments and demands, not least of which is the tricky task of juggling their working lives while trying to enrich and educate their daughters as best as they can within the time allowed between each sunrise and sunset.

The writing is extremely sharp. The background designs are beautiful. The characters are well-developed. The animation is seamless. The fart jokes are infrequent but potent. The music and sound design are evocative, and the stories contained within each six-minute episode strike a fine balance between meaningful and playful without attempting to hit the viewer over the head with anything resembling an obvious lesson or lecture.

Created by Ludo Studio in Brisbane, Bluey has become a genuine cultural phenomenon: since it began screening on ABC Kids in October 2018, its 52 episodes have racked up a combined total of more than 200 million plays on ABC iView, making it the No 1 program since iView launched more than a decade ago.

Nationally, it is the most popular time-shifted program — ahead of the likes of Lego Masters, Utopia and The Handmaid’s Tale — while distribution deals with the BBC and Disney have exposed the Queensland export to millions more overseas viewers.

It’s unfair to characterise Bluey as an unlikely hit, however, as the reasons for its ascension are clear to anyone who has watched an episode.

Among parents of preschool-aged children, it is exceedingly rare to encounter a program that both generations will happily sit and watch together while laughing at the same jokes, even on repeated viewings. But by not talking down to its young audience — and by not smoothing some of the sharper barbs of its more emotional aspects — Bluey has emerged, fully formed, as a show about play and parenting that somehow manages to satisfy both players and parents.

Bandit is a hands-on father whose instincts are tuned to the “yes, and …” maxim of improvisational theatre: instead of shutting down Bluey and Bingo’s incessant game-playing — or, worse, engaging half-heartedly while rolling his eyes — the character is far more likely to throw himself into whatever role is being demanded of him.

Throughout the first season, this work-at-home archaeologist is more of a presence in his childrens’ lives than Chilli, who works in airport security. This inversion of gender norms is significant. Rather than fulfilling a fatherly stereotype of being either an absentee or the bumbling butt of every joke, Bandit is invariably present and engaged with the wild thoughts and imaginative tangents spouted by his two young pups.

‘Your ears don’t hear the gear change, but you feel it in your heart’

Sometimes, though, the show veers into sentimental territory so suddenly that your ears don’t hear the gear change, but you feel it in your heart. Like in the episode Fruitbat, where Bluey can’t sleep because she wants to be outside, doing what a flying fox does at night. Yet on leaving her bed and coming downstairs, she finds her exhausted father asleep on the floor, football in hand, excitedly jerking his limbs about.

“What’s Dad doing?” Bluey asks her mother, who is taping up her hockey stick; importantly, Chilli hasn’t let motherhood get in the way of continuing to pursue her own interests.

“Hmm. I’d say he’s dreaming about playing touch football with his mates,” she replies. “He doesn’t get to play that much anymore, so he keeps having dreams about it.”

“Why doesn’t he get to play it for real life?” Bluey asks.

“Well, he’s busy, sweetheart,” says her mother. “Busy working and looking after you two.”

The narrative doesn’t pause to reflect on the significance of this exchange, which passes so quickly that younger viewers would scarcely clock it, their minds already speeding ahead to the connection that Bluey makes: maybe if she goes to bed, she too can do something impossible while she sleeps.

In her dream, Bluey takes to the sky alongside flying foxes to hang upside-down from trees and gorge herself on fruit — all set to a peppy, Beatles-esque soundtrack — before spying her father running with his mates on a floodlit football field, skirting defenders with fancy footwork and celebrating after scoring a try.

But for the older viewers paying attention, Chilli’s passing comment cuts deep and gets to the heart of what being a parent is: an unending series of life-changing sacrifices and services, much of it thankless, but all of it essential and unmissable.

Upon waking, Bluey is struck by a realisation of the magnitude of what her parents do for her, perhaps for the first time. “Dad? Thanks for looking after us,” she says. “You’re welcome,” he replies, bonking his daughter’s nose and provoking an adoring giggle.

Outside is a busy thoroughfare that runs through Fortitude Valley in central Brisbane; inside and upstairs is a large, open-plan office filled with people hard at work on powerful computers. To the tune of a few thousand mouse clicks per minute, the 50 or so employees of Ludo Studio are building the second season of Bluey, storyboard by storyboard, line by line, frame by frame, joke by joke.

The work of animation relies on intense concentration on the small things that make a much larger whole. About half of the young team wear headphones to block out distractions while drawing on graphics tablets or tinkering with the computer program CelAction. Small teams retreat to a screening room to review their recent work, while in a far corner is a giant television that the crew — and, more recently, some of their children — gather around each Friday at 5pm for the first viewing of the most recently completed episode.

It’s about six weeks until the hotly anticipated second season of Bluey will begin airing on ABC Kids. What’s different this time around?

“Not much,” replies executive producer Daley Pearson with a shrug. “I guess there’s a lot of expectation around it, but it doesn’t feel very different. I think definitely writing-wise, it’s really pulling from the gut again, probably as deep — or even deeper than — season one, by focusing on every family member as much as Dad and Bluey. And the other thing was, it was over half the studio’s first job, and they were trained up for season one. So now, it’s not just their first job; they’ve been doing it for years, so they’re even more brilliant at it.”

Pearson’s fellow executive producer, Charlie Aspinwall, concurs. “It’s nice to develop the characters a bit more, and to broaden the range of what we can do in the episodes,” he says. “I think a lot of the episodes this time are broadly pitched as family comedies, so there’s a lot of episodes set at home, but have the whole family engaged in a game — so that the ‘comedy with heart’ is naturally in there. But it’s obviously a success, so that’s been a big change: we’ve got a lot more work on.”

For producer Sam Moor, its popularity has had the side-effect of simplifying the importance of what she and her team do. “We’re now aware that what we’re making — that we all love — is also now loved by kids and families,” she says. “I think that makes it even more special, that we’re doing something really great and everybody’s loving it. There’s a huge sense of pride that it’s actually found its audience, from the start.”

The voice of Bandit, Dave McCormack, has yet to set foot inside this office, nor has he met his on-screen wife Chilli, who is played by Brisbane-born actor Melanie Zanetti. According to the frontman of indie rock band Custard, he essentially lucked into the job when Pearson was visiting the recording space next door to his studio in Sydney.

“I made it clear I’d never done anything like that before, and I don’t know how to act or anything,” McCormack tells Review by phone. “They said, ‘Do you want to read a few lines?’ And I just read it like I’m talking to you now, and we kept going until we did a whole episode, and it went from there. It’s pretty innocent. It’s certainly not something I ever thought I’d do. I hear they’re not going to dub in American voices [for the US market], so that’s good. We’re going to be teaching Americans how to speak Australian.”

McCormack’s involvement extends to recording his lines for a few hours each month, four episodes at a time, from his studio in Sydney. As a father of two daughters, he finds great humour in the unexpected way in which he has found himself at the centre of one of the country’s most popular television programs.

“There’s little bits of real life in there,” he says of Bluey’s broad appeal. “Sometimes I’m reading the scripts and I’m like, ‘What the f..k? Are they spying on me?’ – because exactly what’s in the script would have happened in my life. Sometimes my family are like, ‘Are you giving them story ideas?’ – but I’m not!”

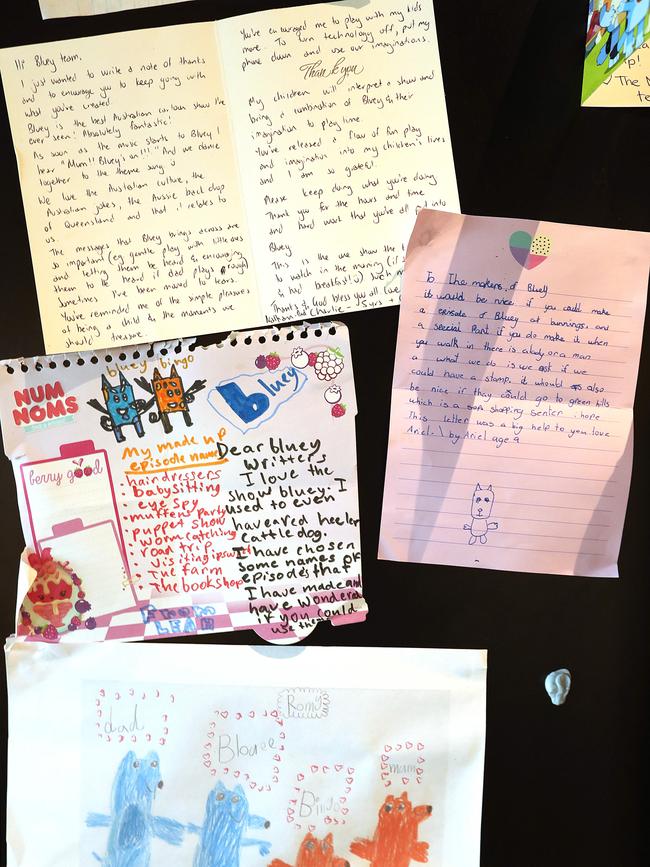

In the kitchen beside the giant TV, a small collection of cards, notes and drawings sent in by viewers of the show are stuck to the fridge. Many of them are written with the unsteady hand and uncertain spelling of small children still coming to grips with expressing themselves through language, but still confident enough to suggest ideas for future episodes they’d like to see.

One observant four-year old viewer even took the time to gently chastise the artists for not being realistic enough in depicting the harness seatbelt that Bluey and Bingo should be wearing while in their car seats. “It’s kids safety!” writes the child. “Bluey, please tell your mum and dad to buy a proper car seat with kids safety.”

In the centre of the fridge, near eye level, is the longest note of the lot. This sort of feedback might be more noticeable to visitors than those who inhabit this space every day, for whom it may have quickly faded into the equivalent of wallpaper once seen more than once. But perhaps for the staff at Ludo Studio who are stretching their legs toward the end of another long day at the desk, this particular letter might prove a tonic for tired eyes.

“Bluey is the best Australian cartoon show I’ve ever seen!” the card begins. “Absolutely fantastic! As soon as the music starts to Bluey I hear ‘Mum! Bluey’s on!’ and we dance together to the theme song. We love the Australian culture, the Australian jokes, the Aussie backdrop of Queensland and that it relates to us. The messages that Bluey brings across are so important […] Sometimes I’ve been moved to tears. You’ve reminded me of the simple pleasures of being a child and the moments we should treasure.

“You’ve encouraged me to play with my kids more,” the writer continues. “To turn technology off, put my phone down and use our imaginations. My children will interpret a show and bring a combination of Bluey and their imagination to play time. You’ve released a flow of fun play and imagination into my children’s lives and I am so grateful. Please keep doing what you’re doing. Thank you for the hours and time and hard work that you’ve all put into Bluey.”

Before it existed as a television show, Bluey existed in the mind of Joe Brumm. He’s not a blue heeler, but the creator and script writer is a bit like Bandit in the sense that he was once a father of two young daughters who frequently engaged in the sort of imaginative play that Bluey and Bingo rope their father into.

For Brumm — a private man who prefers not to be photographed — the show he dreamed up is directly connected to his own experience of parenting.

“It’s sort of like a big, weird photo album of my family’s life,” he says.

“All those games were games we played, and those things that we did in the creek and the markets we used to go to — it all looks different, obviously, but every episode is a weird snapshot that hopefully will keep that alive. I’ll be able to tell the kids, ‘Yeah, we used to do that; you used to be like that’. I don’t know what it’ll be like for me in 10 or 20 years, but I’m hoping it’s like a big time capsule.”

Given that the situations in the show — good and bad; funny and sad — were taken from the pages of his own life, does he ever find himself getting emotional while writing an episode?

“Yeah, when I write the first draft, there’s always one spot in the ep — or maybe one in every two or three eps — where that first hits, and you’re like, ‘Shit’,” Brumm replies. “The first draft of a script, I’ll be like, ‘Holy shit — that was a raw time’. I try to get that in there, and it’s hard to write — but then you start that six-month process [from first draft to final episode]. And then, when someone emails and says, ‘Hey, I was crying during that ep’, you’re like, ‘Oh yeah — that’s right’.”

That scene in Fruitbat where Bandit could only dream of playing touch football with his mates because he didn’t have time to do it — in Bluey’s words — “for real life”? That was Brumm’s reality as a new father, too.

“You don’t feel sorry for yourself — that’s the key,” he says. “You don’t care about yourself anymore, right? You’re like, ‘Oh, I don’t get to play footy anymore’. But all those things were real, and they’re things I remembered. You don’t take a poll; you just write what’s going on in your life, and it’s always nice when you realise you’re the same as everyone. I quite like that experience.”

Every parent knows the feeling: when you create life, your own needs are diminished in the face of this new creature before you, which takes so much love and time and energy each and every day — a bit like creating a television show.

But things change, and as his daughters have gotten older, the creator of the nation’s favourite children’s program is happy to report that he has now resumed playing touch football each Thursday night with some of his colleagues — not in his dreams, but for real life.

The second season of Bluey screens exclusively on ABC Kids from Tuesday March 17, daily at 8am and 6.20pm.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout