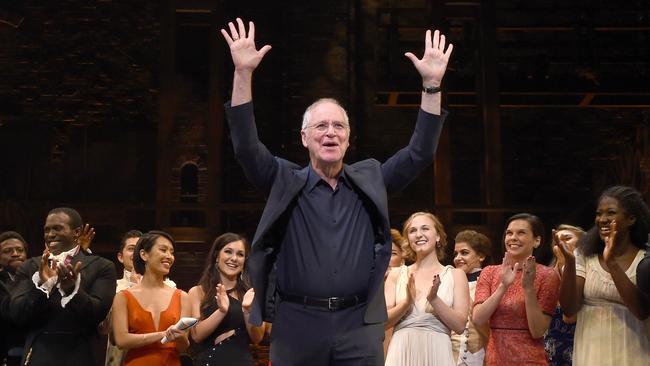

Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda plays his best shot

Alexander Hamilton’s life, told in hip-hop, is a fantastic score, the lyrical rendering of real-life events is clever. This is history for grown-ups.

If Lin-Manuel Miranda has worked out the secrets to the success of his blockbuster hip-hop musical, Hamilton, he is not sharing them.

“If I have, I’m not telling,” he tells Review. “I thought there was an extraordinary story to be told and I thought hip-hop was probably the best way to tell it. If you tell it in a more traditional opera form, it’s 12 hours long. You need hip-hop to tell the story.”

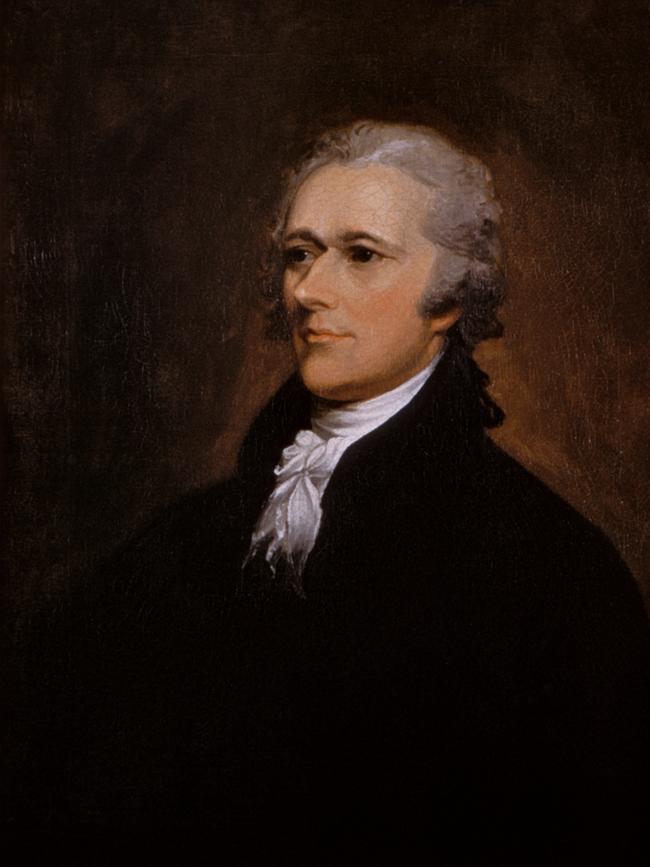

The story of Alexander Hamilton – “the ten-dollar Founding Father without a father” – is indeed compelling. Immigrant. Patriot. Revolutionary. Lawyer. Banker. Politician. First Treasury Secretary.

Telling this story required Miranda to dive deep into historical documents and wrestle with truth and fiction in and around the all-singing, all-dancing, cast of characters. Hamilton is, of course, the star of the show. But does his star still burn brightly today?

The US has been convulsed by racial issues in recent years. The notion of Lady Liberty welcoming immigrants has also been under strain with xenophobia rearing its ugly head. The founding fathers, venerated for generations, have had their legacies reassessed as marble statues have fallen.

Hamilton, like all founding fathers, is flawed. He was anti-slavery but not an abolitionist. He thought republican government should be the preserve of the elites. He was not entirely welcoming of new immigrants and supported the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts. He was unfaithful to his wife. He was tempestuous and hot-tempered, which led to an ill-fated duel with nemesis Aaron Burr. The musical does not gloss over these imperfections and contradictions.

Miranda says he felt “incredibly intimidated” trying to turn Hamilton’s life into a musical. Playwright John Weidman suggested he focus on the aspects of Hamilton’s life that he thought could be musical such as meeting George Washington for the first time.

“In research and lots of reading you find your way into all of those characters,” Miranda explains. “I can’t even pretend to have a historically accurate depiction of anybody before breaking into song. So, my goal was to really stay connected to the initial impost of why this was a good idea and why this story resonates with me.”

That germ of an idea came when Miranda was on vacation in Mexico in 2008. He relaxed into a hammock and began reading Ron Chernow’s masterful biography of Hamilton (2004). He immediately thought this would make a good musical. He not only wrote the music and lyrics but portrayed Hamilton too.

“He had lived through this Dickensian childhood with more trauma than I can remember seeing in any biography I’d read,” Miranda says. “And then he writes his way out – he literally writes an essay that is so good that people give him money to read it – and when I reached that moment in the story I thought that is a hip-hop story.”

“Writing your way to reinvention is something that I recognise in all of my favourite rapper’s first albums – whether that is Reasonable Doubt (Jay-Z) or Ready to Die (The Notorious B.I.G.) or The Slim Shady LP (Eminem) or Tha Carter (Lil Wayne) – this notion of writing so specifically about your circumstances that you transcend them because other people understand.”

On his return to New York, Miranda tracked down Chernow and invited him to see his award-winning musical, In the Heights, which premiered in 2005. Backstage, he asked Chernow to act as historical consultant for the Hamilton musical. Intrigued, he agreed.

Chernow tells Review that his biography of Hamilton had been optioned three times by Hollywood but never got made into a film.

“Hamilton was brilliant, handsome, dashing, charismatic,” he says. “A self-invented figure who arrives in North America not knowing a soul and ends up as a Founding Father of the country. It was never difficult to picture him as a leading man.”

It took Miranda six months to write the opening number:

Burr: How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a

Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten

Spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor,

Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?

John Laurens: The ten-dollar Founding Father without a father

Got a lot farther by working a lot harder

By being a lot harder

By being a lot smarter

By being a self-starter

By fourteen, they placed him in charge of a trading charter.

Thomas Jefferson: And every day while slaves were being slaughtered and carted

Across the waves, he struggled and kept his guard up.

Inside, he was longing for something to be a part of,

The brother was ready to beg, steal, borrow or barter.

James Madison: Then a hurricane came, and devastation reigned,

Our man saw his future drip, dripping down the drain,

Put a pencil to his temple, connected it to his brain,

And he wrote his first refrain, a testament to his pain.

Burr: Well the word got around, they said, “This kid is insane, man”

Took up a collection just to send him to the mainland.

“Get your education, don’t forget from whence you came, and

The world’s gonna know your name. What’s your name, man?”

Alexander Hamilton: Alexander Hamilton.

My name is Alexander Hamilton.

And there’s a million things I haven’t done

But just you wait, just you wait …

Miranda describes Hamilton as “a love letter” to both hip-hop and archetypal musical theatre. Burr as a narrator is inspired by Judas in Jesus Christ Superstar. Hamilton draws from musicals about “communities” such as Cabaret and Fiddler on the Roof. And also “period” musicals with a central character as the “engine of the story” such a Gypsy, Sweeney Todd, and Les Misérables.

It took Miranda a year to write My Shot, the pulse lifting musical number that encapsulates Hamilton’s youthful ambition:

Hamilton: I am not throwing away my shot!

I am not throwing away my shot!

Hey you, I’m just like my country,

I’m young, scrappy and hungry,

And I’m not throwing away my shot! …

In any page-to-screen dramaturgical process, liberties must be taken that require a balancing of history with entertainment. Maybe historians should relax a little and accept Hamilton as it is. After all, as Miranda says, “the show is the show is the show”.

The lyrical rendering of history is clever. Hamilton’s riposte to Jefferson in Cabinet Battle #1 – “A civics lesson from a slaver” – is on target. How Hamilton won agreement to assume state debts and establish a national bank in return for setting the capital in Washington – “The Room Where It Happens” – is a lesson on realpolitik. Describing how a 19th century duel works – “Ten Duel Commandments” – is ingenious. The contribution immigrants have made to America is rightly celebrated: “Immigrants, we get the job done,” Hamilton says to the Marquis de Lafayette on the Yorktown battlefield.

“As with any stage adaptation of historical events, there’s a lot of dramatic license,” Chernow accepts. “History is long, messy and complicated. Broadway shows have to be short, coherent and tightly constructed. I love that Lin never departed from the facts in a capricious manner and always had a sound dramatic reason for doing so.”

The biggest surprise for Chernow was seeing black and Latino performers play the founding fathers during rehearsal. The cultural impact of this decision – having the story of old America told by those who encapsulate the diversity of the new America – was seismic. But it was not surprising for Miranda.

“This is a hip-hop story so it only makes sense that black artists and artists of colour are the ones telling the story,” he says. “When it was a mixtape in my head, I was just thinking in terms of voices, so I wasn’t even picturing it, it was just music. When I was in the development of the show I went to the most talented hip-hop and R&B artists I had as friends.”

“So, I called Chris Jackson and I said, ‘You are playing George Washington.’ I called Daveed Diggs and said, ‘Come be Lafayette and Jefferson.’ So, it was always a part of the process. I think the biggest surprise was how much of a big deal it seemed to be to everybody else. But for us it was baked into the initial impulse.

“I have been incredibly grateful to see that it kicked open a door that I think some people didn’t realise existed in their minds. You know, the notion that of course the stage should be filled with a group of actors that looks the way the world looks. Why don’t we see more of this?”

The Australian production of Hamilton has a diverse cast, led by Jason Arrow. “I’m so proud that we cast it locally,” Miranda says. “That was very important to Australia, and to us as a creative team, that this company has ownership over telling the story and that you will see that same diversity in the production.”

Issues of race, immigration and the founding fathers’ legacies were live issues when Hamilton opened off Broadway in 2015 and they were re-litigated when the filmed version was streamed on Disney+ in 2020. And they will again prompt discussion when Hamilton opens in Sydney this month.

“What’s happening today doesn’t change how our founders behaved two hundred some odd years ago,” Miranda says. “They all lived with the original sin of slavery, which is a stain on their reputations, and that doesn’t change now.

“I think that moments that didn’t necessarily pop when that was not in the forefront of people’s minds pop differently now and I embrace that.”

Chernow judges Hamilton’s record on slavery as good but by no means perfect. The Schuyler family that he married into were slaveholders. Yet Hamilton was involved in several anti-slavery activities. He almost certainly never owned slaves but it is likely he acted as go-between for the purchase of two slaves by his sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler.

“During the Revolutionary War, he championed a plan to emancipate any slave who picked up a musket for the Continental cause,” Chernow explains. “After the war, he was a co-founder of the New York Manumission Society, which lobbied for the gradual abolition of slavery. And in his final years, he represented, as a lawyer for the society, blacks who were picked up by slave-catchers on the New York streets.”

Chernow believes Hamilton, the musical, does a good job in capturing Hamilton, the man.

“We find the Hamilton story irresistible because he was so smart that we admire him and so terribly flawed that we can identify with him,” Chernow says. “It’s rare for a musical to present the sort of rich, complex portrait of the central character that we would expect to find in a fine novel. This is history for grown-ups. Lin never talks down to the audience. Rather, he lifts them up to a high level of erudition without sacrificing anything in terms of entertainment.

“Hamilton’s story echoes a myth found in many fairy tales about an orphaned child, poor, friendless, and alone, who grows up and becomes a prince or princess. We all love tales of people who could easily have been defeated by early adversity and instead are toughened by it and emboldened to shoot for the moon. Hamilton could not have started out with less or ended up with more.”

There are universal themes in Hamilton’s story that resonate with audiences everywhere. If there is a secret it is that the musical offers a deeper examination of a life that, for many, prompts a revealing look into their own lives and history.

“It grapples with how finite life is and it grapples with how we all remember, and how that changes over time,” Miranda says. “We all hope that we are remembered in some way shape or form, whether it is for our work or for our children, our children’s children. I think that is the stuff that people will take with them when they leave the show.”

Hamilton officially opens at the Sydney Lyric Theatre on March 27

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout