Graham Nash and the moment music changed forever

Graham Nash knew Bob Dylan’s songs could not be improved. So Nash left The Hollies rather than record an album of cover versions, setting off a musical chain reaction leading to one of the greatest groups in history.

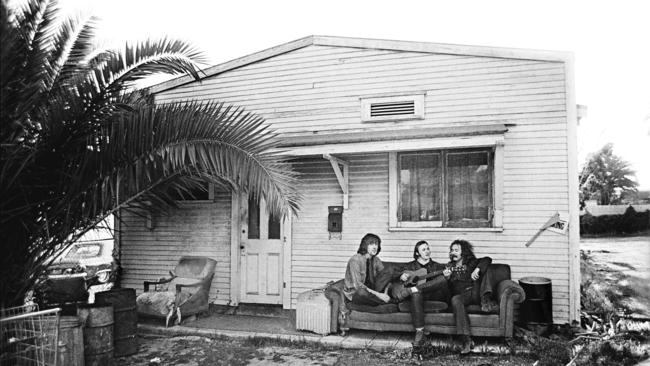

It is a parking-lot eyesore today but, in 1969, on it sat a tiny wooden house near the end of its life at 815 Palm Avenue in West Hollywood, between the famous boulevards of Sunset and Santa Monica.

A young Englishman had walked past it days before. He liked to take photographs and regretted not having his camera that afternoon.

He had just started a band with two Americans and they were halfway through recording an album together.

A few days later, they were with legendary rock photographer Henry Diltz – known for working quite spontaneously – who was to shoot the cover image for it. Graham Nash told Diltz about a rundown house he had seen.

They drove there and, before Diltz had his gear out of the car, Nash was sitting on the frayed brown couch whose best years were well behind it. He was resting on its back with his booted feet on the cushion. Multi-instrumentalist Stephen Stills sat cross-legged to his left with an acoustic guitar on his lap. Making up the trio, further to the left, was David Crosby, one foot on the ground, the other on the seat.

In minutes, Diltz had all the photos he needed and that afternoon sent them off to Kodak for processing into transparencies. That would take two days.

The three boys had come from bands: Nash from England’s the Hollies, Stills from Buffalo Springfield, and Crosby from the Byrds. They spent the following day thinking up band names before settling on their own, in the easily uttered order of Crosby, Stills and Nash.

A day later Diltz dropped over with the transparencies, a projector and a 12-inch by 12-inch piece of white cardboard replicating the size of a vinyl album sleeve. He projected his images on to it and the band members were delighted. In an era of swirly psychedelic typefaces and abstract and often indistinct images that dripped over the edge, Diltz’s perfectly composed photographs were simple and clear – like the detailed harmonies of the songs the band was writing and recording.

But they were sitting in the wrong order. Diltz could have reversed the image, but the right-handed Stills was holding a guitar and would have been rendered left-handed. They hopped back in a car with Diltz to reshoot it, but when they arrived at the address the little house had been demolished, the couch gone – it and all the timbers bulldozed to the back of the block. None was keen that they should be Nash, Stills and Crosby, it sounds so unwieldy. It stayed as it was and the album of that name was issued in March that year, its cover becoming one of rock’s best known.

It is easy to look back on the pedigree of Crosby and Stills and Nash and assume the union would be a supergroup smash. But Stills’s band had had just a single hit with the song For What It’s Worth. Crosby’s band had had three hits including its take on Bob Dylan’s Mr Tambourine Man (the only song written by Dylan to top the Billboard chart) but on which Crosby did not play, and in any case, by the end of 1965, the Byrds had fallen to earth. Nash was barely known in the US. The Hollies had 14 top 10 hits at home, but just three in the US with Nash and then another three after he left the band to form CS&N.

But singer-songwriter John Sebastian had been listening and was aware that the high tenor in the Hollies glorious harmonies had been Nash. He heard that voice again in 1968 while lounging beside Cass Elliot’s swimming pool in Laurel Canyon in the Hollywood Hills. Before the Mamas and the Papas, Elliot had played in a band with Sebastian. Gathering regularly at Elliot’s house were Joni Mitchell, the Monkees’ Micky Dolenz and Peter Tork, Eric Clapton, and Stills and Crosby, who were unemployed and keen to start a band. Many people take credit for what happened next, but all agree that it was Sebastian who told them they should include Nash’s unusual light tenor in the mix of the already refined Stills-Crosby harmonies. He told Stills: “There are two great high-harmony singers in the world right now: One is Phil Everly, the other is Graham Nash.”

Nash was out of the Hollies by July 1968. He just hadn’t told them. He had hated their idea of recording an album of Dylan songs – he didn’t think they could be improved.

“I was completely against it,” he told me speaking on a stopover during a recent European run of dates. “I did do Blowin’ in the Wind and I hated it. I don’t like treating Bob Dylan’s music like that.” Instead, he offered the Hollies an adventurous song he had written, Marrakesh Express, but the band rejected it.

Band-less in Laurel Canyon, he gravitated to his mate Crosby whom he’d met in Britain when the Byrds had toured. Soon he was in a relationship with Mitchell – her first album, Song to a Seagull, has recently been issued – and living with her in a bungalow up the hill at which he would write on her piano the song Our House.

Practising at house parties and by the pool songs they had just written – parts of what became Suite: Judy Blue Eyes (about Stills’s girlfriend Judy Collins), Crosby’s complex Guinnevere, and the obvious hit Marrakesh Express – it was clear to their fellow musicians their harmonies were unique and beautiful. They couldn’t wait to get to a studio and start recording them.

They did low-key gigs around Los Angeles, some of which Doors’ producer Paul Rothchild caught. “They threw their shit up the flagpole to see if anyone would salute. Well, not only did the people salute, they fell down to their knees. Crosby, Stills and Nash could have started a religion.”

Nash felt it, too, and returned to England briefly to break the Hollies’ hearts. He’d formed the band with school friend Allan Clarke, who commented with sadness at the time: “He’s always been ahead of me ... right from the beginning.” Clarke added: “What the hell are we going to do?”

The first CS&N singles charted strongly and the first album revealed not just a new act but a prodigious marriage of folk and rock none of their previous bands had been able to sustain.

Mitchell, Carole King, Carly Simon and James Taylor soon would eddy away in a similar vein, while the Eagles, America, Little Feat, Bread, Seals and Crofts, Jackson Browne and post-Monkees Mike Nesmith would consolidate the sound to build careers on it. Even the Beach Boys, who had been at the birth of this movement, chimed in with their last great albums Surf’s Up and Holland.

Stills played so many instruments so well he was called not a multi-instrumentalist but a mega-instrumentalist; as well as six and 12-string guitar, he is proficient on piano, organ, drums, clavinet, bass, banjo and even the Trinidadian steelpan. His Suite: Judy Blues Eyes, in all its complexity, will be played as long as skilled musicians who can sing choose to stretch themselves. His multi-layered Carry On – with its time signature changes and Hammond organ – is also in that league.

Crosby might have been just a distinctive singer and guitar player – and a wearisome, drug-addled, gun-slinging braggart – but his songs on the first CS&N album and its follow-up with Neil Young (as CSN&Y) raised the band’s output from exceptional to luminous. Apart from Guinnevere, he wrote with Stills Wooden Ships (on his Florida-based schooner Mayan) and Long Time Gone, as well as the title song to the follow-up album Deja Vu, and on that album its counterculture high point Almost Cut My Hair.

He would intermittently match this genius, but just as the band’s debut album sat high in the US charts in September 1969, his girlfriend, Christine Hinton, was killed in a car accident while ferrying their cats to the vet.

He identified her body. Her ashes were spread from the Mayan. He would never be the same.

It was Nash who pulled it all together – as the ethereal tenor harmonist, the writer of simple, chart-friendly songs, not least of which Teach Your Children, that some thought sailed not far enough north of nursery rhyme. But there was something about Nash’s skeletal melodies that invited others to fill their vacuums with inventive musicianship.

Take Marrakesh Express. The lyrics recall a 1966 train journey Nash took to Marrakesh from Casablanca. As much as Dylan’s Hurricane is a news report on the fate of boxer Rubin Carter, so too is Nash’s song true reportage. But the song is raised by the crisply penetrating overdubbed dual electric guitar lines and Jim Gordon’s clever shuffling drum part that mimics a rattling train in motion (Gordon played with Steely Dan, that’s him on Classical Gas, Layla and George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass – he died a year ago in jail where he had spent nearly 40 years after murdering his mother).

Similarly, Teach Your Children, a song inspired by the disturbing 1962 Diane Arbus photograph of an angry-looking boy holding a hand grenade in New York’s Central Park, is animated by a lively pedal steel melody played by the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia. It and the song are beautiful, but sans Garcia it would hardly have stood out.

Unlike the others, Nash hit the charts – on his own and with permutations of the bands – regularly for a few years in the early 1970s. Stills had a hit with the jaunty Love the One You’re With, effectively a CS&N song with the boys singing harmonies along with Sebastian and Rita Coolidge – her leaving Stills for Nash is sometimes cited as the reason CS&N broke up the first time (her boyfriend before them had been killer drummer Gordon).

Nash’s 1971 song Chicago started with the words: “So your brother’s bound and gagged and they’ve chained him to a chair.” This is a reference to the nasty Black Panther boss Bobby Seale, who with comrades had led disturbances at the infamously riotous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. In court Seale constantly interrupted proceedings and called the judge a fascist, racist and pig. The judge had him gagged and restrained. The accused were called the Chicago Eight. The song’s memorable chorus – “we can change the world” – included Coolidge and Australia’s Venetta Fields.

Its refrain of “rules and regulations who needs them” prefigured by weeks John Lennon’s line in Imagine “imagine there’s no countries, it isn’t hard to do”. Such naivety was common at the time. Nash met a few of the Eight, later conceding that “they weren’t all saints of course and later, a couple of them did some bad things”. He still sings it and it goes down well, particularly in Chicago where he sang it last year. Another song on his first album, Songs for Beginners, was Military Madness and refers to his birth in the first years of World War II:

In an upstairs room in Blackpool

By the side of a northern sea

The army had my father

And my mother was having me.

That Nash has backed the underdog most his life has to do with an extraordinary episode when he was 14. His father had always taken photographs and in a makeshift darkroom at home developed the results.

The young Nash thought it magic. In 1952 his dad bought for him an Agfa camera from a work colleague, but it turned out to be stolen property. When the police came calling at the family home, Nash Sr nobly refused to dob in the offender and was cruelly jailed for a year.

These days Nash is enjoying transcendental meditation and says he wishes he had discovered it 50 years ago. “It makes me believe in myself. It makes me realise that I am an ordinary person. I know that I have done something different with my life … It makes me realise that I am an incredibly lucky man.”

I ask him if he remembers what he was doing on February 3, 1959, the day his first band’s namesake, Buddy Holly, was killed. “I was standing on the corner of an apartment building that my family lived in, he recalled. “I was with Allan Clarke who started the Hollies with me in December of 1962. And we were indeed, both of us, in tears that day.”

Nash, like Stills and, up until he died in January last year, Crosby, stuck firmly to their hippie political will, best articulated in the line from Almost Cut My Hair: “I feel like letting my freak flag fly.” It defined nonconformist, perhaps unconventional behaviour.

And while a lifetime might moderate us all, these days Nash and Stills maintain the rage against the Republican candidate, likely to be Donald Trump, as he sets himself to run America again. Stills wrote a song on protest against Trump in 2016. Nash adds about Trump: “I hope he’s going to be in jail before he gets to be president again.”

Nash is the oldest survivor of that remarkable, if brief, era – the influence of which on music, given its duration, was unprecedented – and will be in Australia next week. The set list, if he sticks to recent concerts, covers all bases, from the Hollies’ Bus Stop to Marrakesh Express, Chicago and beyond.

Graham Nash plays Palais Theatre, Melbourne, on March 7; Adelaide Entertainment Centre on March 13; His Majesty’s Theatre, Perth, on March 16; Sydney Opera House on March 19; Civic Theatre, Newcastle, on March 20; Anitas Theatre, Wollongong, on March 23; QPAC Concert Hall, Brisbane, on March 26; Twin Towns, Tweed Heads, on March 27. Tickets via DRW Entertainment.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout