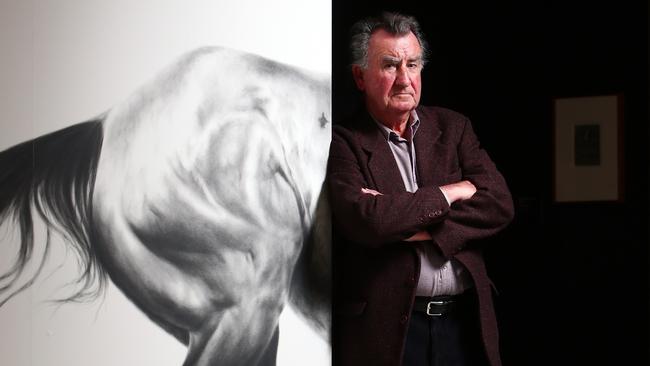

Gerald Murnane mugged by nostalgia on the racetrack

Gerald Murnane’s Something for the Pain is as much an autobiography as a memoir of the turf.

In the 1980s, Gerald Murnane, already an admired novelist, was lecturing at a college of advanced education in Melbourne and didn’t really fit in, which should surprise no one. It is hard to think of anyone less suited to collegiate frolics — an observation, one should add, that is offered as a bouquet. Murnane has been ploughing lone furrows since before they became cliches.

He pinned only three pictures on the large display board above his college desk, even though it had room for at least 30. There were portraits of Emily Bronte and Marcel Proust. The third item came as two blurry newspaper photographs of the racehorse Bernborough. The first showed the big stallion in about 20th place at the top of the home straight in a Brisbane race during 1946. The second, taken at the finishing post, showed Bernborough winning the race after producing one of those electrifying sprints that had enshrined him in folklore.

STORY: Gerald Murnane talks horses and courses with Stephen Romei

No snaps of Che Guevara, who turned stubble into a fashion statement, or of Gough Whitlam martyred on the steps of Parliament House. Just two authors and a horse. But it was right enough. There was a pattern here, and Murnane likes patterns.

Murnane smiles on Bronte and Proust (to whom he has sometimes been compared), as well as Henry James. But he loves horseracing, if in a way that sets him up as a true eccentric. He sees it as a metaphor for life and the human condition and, sometimes, “a sort of higher vocation excusing us from engaging with the mundane”.

Murnane explains in this charming memoir that his work colleagues “seemed to have assumed that because I was a writer I was like them in having left-wing political beliefs, reading The Age and tuning in to the ABC”.

He liked to provoke them. “Sometimes, after I had drunk a good deal, I used to argue that horseracing had as much to teach us as had Shakespeare and certainly much more than some of the pretentious films and plays that they were fond of praising and discussing.”

One night he told them the story of Bill Coffey, the owner-trainer from New Zealand. Coffey would work in the timber mills until he had saved enough to buy himself a new racehorse. In 1964, one of these ran fifth in Polo Prince’s Melbourne Cup. Late in the following decade, Coffey was back at Flemington with a steeplechaser called Lord Pilate. Murnane was in the grandstand when, amid drizzling rain, Lord Pilate fell at one of the fences in the straight. He lay on the track, alive but unable to rise.

Track workers began erecting the green canvas screen. Then Murnane saw a man wearing a long oilskin coat running towards the horse, the coat flapping and hindering him, “making him look like an ungainly or crippled bird”. The man flung himself down on the grass next to the horse, put his arms around its neck and pressed his face against its head.

The man went on lying there. The light rain went on falling. The vet and the track attendants stood without moving. They were not embarrassed. They were merely being respectful. They were horsemen too. They went on standing patiently. They went on waiting until the old man, the timber worker and part-time owner-trainer, had spent the measure of his grief.

This is Murnane, the stylist, at his best. Short declarative sentences, all muscle and bone. Every word and punctuation mark mulled over so that it earns its place and sits just right. Imagery made stronger by the deliberate repetition of words, in this case “went on”. The prose itself plain and unsentimental but producing a cumulative effect that prods at your heart. No purple flights, no showing off.

You sense a man forever straining to tell what he believes to be the truth. There has always been a stubborn honesty to Murnane’s work. Something for the Pain is an unusual book by an unusual man and the charm is in the prose. And if you are a Murnane admirer, you will learn more about him from this than anything he has written before.

If racing has not spawned a body of literature to match those owned by cricket and boxing, it has still produced some fine wordsmiths, and the forces that inspired them make nice contrasts with the obsessions of Murnane. Among Australians, ‘‘Banjo’’ Paterson, an amateur jockey and polo player, was fascinated by the horse itself: its lineage, moods and, above all, its heroics. Neville Penton in his A Racing Heart told us in sparkling prose about The Closed Society: the trainers, jockeys, strappers and hangers-on who meet in the dark at racetracks every morning and live in a bubble of their own, and by rules that they alone understand. Among the Americans, we have the journalist Joe Palmer, a peerless stylist, who first of all saw racing as a way of life, leisured and mannered, which is the way he wrote. And there is Damon Runyon, who fashioned racing’s losers and battlers into philosophers and wags, and also understood one of the great truths: that at any time on a racecourse someone somewhere is plotting larceny.

Murnane is like none of these. He has never sat on a horse. He didn’t walk on to a racecourse until he was 15. He likes to bet but, as he puts it, timidly. He is captivated not so much by horses, pedigrees or racetrack characters as by the colours and patterns of the jockeys’ silks and what these symbolise, by the derivation of horses’ names, by the crescendo and diminuendo of the racecallers, by the way the story of a race can be told in time to the 1812 Overture, by a search for a symmetry that only he fully understands. He is bewitched by racing’s music and aesthetics. To him, it is a pageant that keeps teasing the senses, drawing him back, week after week.

His enjoyment of the sport, he writes, is “a solitary thing: something I could never wholly explain to anyone else”. And in another place: “Racing provides me with a set of beliefs and a way of life.”

It began with a dreamy boy at Bendigo staring at grainy photographs in the midweek Sporting Globe, reciting the names of horses and conjuring up images of what those names stood for. A horse called Hiatus, for instance, became a bird in flight above a deserted seashore or estuary. Then he saw his first set of colours, on a trotter at the Bendigo Showgrounds, and another obsession began. And so this book ends up as a delightful procession of memories, an evocation of a world that has gone and isn’t coming back.

His memories remind you of your own. Murnane was there when 20,000 people, most of them men in gabardine overcoats, turned up to an ordinary winter meeting at Flemington, tumbling out of dirty red trains that came with brass door handles. When the west wind off the Maribyrnong River sent clouds of cigarette smoke scudding across the course. When there were no off-course totes and SP bookies lurked in cobbled lanes and rode around country towns on bicycles, taking half-crown bets from old ladies who listened to the races on radios the size of refrigerators.

When Flemington, the suburb, wasn’t gentrified and peppercorn trees wept in the summer heat and calves bleated in those saleyards that seemed to go on forever and the wind carried the blood-and-mud whiff of the abattoirs. Back when hundred of bookmakers turned up on course every Saturday and used black crayons to scribble graffiti on betting tickets. When racing was in the mainstream of sports, off limits to corporates who would later turn it into a seven-days-a-week casino that most of the time is soulless.

Murnane remembers all this and several times refers to “the Great Age of Racing”. It could be that Murnane and I have been mugged by nostalgia. Maybe racing back then was no better than it is now, but it certainly seemed more interesting. The news that an Arab potentate has, on a whim, bought himself a new horse for $30 million, or that Australians may now use some electronic device to bet on trotting races in Indiana, or that racing’s bureaucrats have a new “strategic plan” complete with umpteen bar charts — these things somehow fail to wriggle their way into one’s heart.

This book is as much an autobiography as a memoir of the turf. Murnane’s wife, Catherine, died a few days before the Blue Diamond Stakes meeting at Caulfield in 2009. Long before this the couple had made a pact. The first of them to die would arrange from the spirit-world for the surviving partner to back, on the first Saturday after the other’s death, a winner at odds of 20-1. Murnane duly backed Reward for Effort in the Blue Diamond. It was showing 16-1 when he got set but it started at 20-1 — and won.

A few years ago Murnane was mooted as a possible Nobel prize winner. British bookmakers quoted him as short as 8-1 in pre-post markets. One is inclined to think Gerald, thoughtful punter that he is, would have hung out for 20-1 — and also had a saver on the Peruvian weight-for-age performer Mario Vargas Llosa.

Les Carlyon’s books include True Grit: Tales from 40 Years on the Turf.

Something for the Pain: A Memoir of the Turf

By Gerald Murnane

Text Publishing, 288pp, $29.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout