Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s unheard songs to be released in bold deal with Universal

The Indigenous star left behind a trove of unreleased songs that will come to life through a bold new deal

That high tenor voice could stop you in your tracks: at once achingly tender and deeply powerful, it resonated with listeners from Sting and Elton John to members of the Gumatj clan on Elcho Island, off the Arnhem Land coast.

When Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu died, aged 46, at the Royal Darwin Hospital in 2017, Australia suffered a tremendous cultural loss, says Cyrus Meher-Homji, a senior vice-president at Universal Music Australia. Meher-Homji, who works in Universal’s classics and jazz division, asks: “Had he lived on, what might he have given the world? … I think he would have gone on to cement what original Australian music really means. He was well on the way to defining that, and he was taken away from us.”

Against daunting odds, Gurrumul, who was born blind and was raised on Elcho Island (or Galiwin’ku), became one of the country’s most successful performers: Rolling Stone called him “Australia’s most important voice” and he performed for Barack Obama and the Queen, bringing his singular interpretation of his beloved Yolngu culture’s songlines to mainstream audiences.

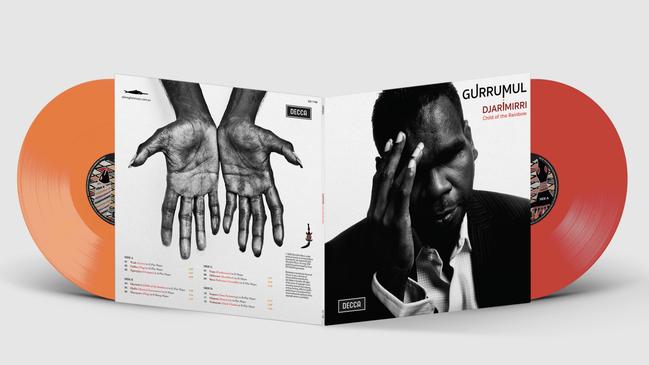

Across a relatively short solo career (2008-17), Yunupingu — a largely self-taught musician who famously played a right-handed guitar upside down — produced four award-winning studio albums, while his first album, simply titled Gurrumul, sold 500,000 copies. His final album, Djarimirri (Child of the Rainbow), was completed before he died and was released posthumously in 2018.

A fusion of orchestral music, traditional songs and harmonised chants, it became the first Australian Indigenous language album to top the ARIA charts.

Now, in a startling move, Gurrumul’s long-time label, Darwin-based Skinnyfish Music, and international music giant Universal have struck a far-reaching deal that will ensure the singer-songwriter’s voice continues to be heard from beyond the grave for years to come.

Under the deal, revealed exclusively to Review, Gurrumul’s back catalogue and future releases — to be drawn from a trove of completed and partly completed songs created before Gurrumul’s death — have been signed to the Universal label Decca Records. Universal Music Australia and New Zealand president George Ash says of this highly significant signing: “The arrival of Gurrumul is a deep and genuine privilege for all of us at UMA … We look forward to taking this (the singer’s legacy) to a much broader audience both in Australia and also around the world, while also helping see some of Gurrumul’s unfinished works come to light.”

Meher-Homji says the deal follows five years of talks between Skinnyfish Music and Universal, one of the world’s biggest music companies. Decca has already drawn up an ambitious three-year plan for the singer’s oeuvre, kicking off with a re-release of his single Maralitja: A Tribute to Yothu Yindi, this month (Gurrumul was once a member of Yothu Yindi) and culminating with a series of collaborative albums featuring the singer’s unreleased works.

“It’s quite a far-reaching plan, not only using existing material but reinventing existing material and presenting it in different ways,’’ he says.

Skinnyfish Music creative director Michael Hohnen says the deal with Universal is aimed at taking the singer-songwriter’s music to “a much broader audience” than the tiny Darwin label — which has managed the singer’s career since 2008 — could reach. A partnership with a much bigger company was “the only way we could see that his legacy is going to be able to be presented nationally and internationally in a way that is going to get the coverage that it deserves,” Hohnen says.

He says Gurrumul left an incredible legacy “but I don’t want that to fade away”. Like Meher-Homji, a former music critic with The Australian, he says “we’ve only probably just touched the surface” of the proud Yolngu man’s global appeal.

So what is being planned? In March, Decca intends to release legacy editions of all four Gurrumul albums on coloured vinyl, with two albums, Rrakala and The Gospel Album, issued on vinyl for the first time. It will simultaneously release a CD box set of the singer’s catalogue, with some additional material.

In July next year it will launch a “best of” or legacy album aimed at reaching untapped global audiences. With this album, Meher-Homji says “we’re working towards taking Gurrumul to the world … He has a reasonable following in the UK, Germany and the US. They’re the three markets that know about him but we want to go much, much further.”

Interestingly, Decca has big plans for “a deep archive” of Gurrumul recordings, compositions and experiments that have never been heard by the public. From 2022, it intends to incorporate these works into three albums — a vocal duets, piano duets and remix album. According to Meher-Homji, it’s hoped these albums will feature collaborations and improvisations with “heavy-hitter” musicians and singers from Australia and overseas, including artists from Universal’s vast roster. Such albums, he says, “would be a wonderful way of putting his music out there and again reinforcing the universality of it”.

He adds: “The published legacy of Gurrumul isn’t that big, really — four studio albums is very slender — that’s why we’re challenged to think of these new and different ways to introduce Gurrumul’s voice to the world.”

He won’t reveal how much the deal was worth but says that ensuring Gurrumul’s family benefits financially from the signing and future royalties “was foremost in our minds” during the negotiations. Both Universal and Skinnyfish told Review this principle was “very, very important”.

Crucially, Gurrumul’s family is on board with the decision. While many traditional Indigenous clans consider it taboo to invoke the names of dead loved ones, Hohnen says Gurrumul’s relatives decided soon after he died that “he was so well known and so revered, it would be a negative thing to stop his name being out there. His family are carrying on this mantle of what he’s been able to produce.”

From Elcho Island, Yolngu ceremony leader Don Wininba Ganambarr, who is married to Gurrumul’s sister Jennifer Djapu Yunupingu, tells Review that showcasing the unreleased music globally is “a good thing” as it “lets them (the public) know that Gurrumul lived by those songlines”.

Asked how he remembers the singer, he says: “Every funeral time or ceremony he sits by the side of his leader and he listens to every word that they’re singing and it’s been there for hundreds and hundreds of years — the songline’s been there, the stories have been there — we’re trying to give that one back to the public.”

Universal hasn’t yet revealed how many unreleased, complete or nearly complete songs there are because it is still assessing the archive. The trove includes a 25-minute orchestral work Gurrumul wrote, while Hohnen says he and the singer were working on the piano duets and remix projects (as well as Djarimirri) in the years before he died.

Although Gurrumul was best known for his traditional songs, Hohnen says the singer “loved” the remix genre, partly because Yothu Yindi’s hit song Treaty, which Gurrumul co-wrote, “took off” in that format. “That was kind of his big apprenticeship to the music industry,” he says. (He also performed in the Saltwater Band before going solo.)

Skinnyfish will be involved in shaping the unreleased songs and compositions, and Hohnen says candidly: “I’ve spoken to Cyrus about the need to be careful. I don’t want to scratch up anything he ever tracked with us and make something out of it.” Meher-Homji is also aware of the need to be discriminating: “I think our task is how we mine this (archive) intelligently. Not just, ‘Here are two albums of unreleased material’ … It takes much more craft than that.”

One of Gurrumul’s previously released songs, a traditional work about his white cockatoo totem, has been incorporated into the Midnight Oil song Change the Date, which features on the band’s just-released Sony album, The Makarrata Project. Hohnen says he and Gurrumul worked on the white cockatoo song “back in the studio in 2012 when he was completely on fire”. It is “the first new Gurrumul piece to be produced since he died”, he says, and demonstrates how posthumous collaborations can be “powerful and touching”.

A classically trained musician and double bass player, Hohnen was a spokesman for the publicity-shy singer and often appeared on stage with him. He is still mourning his friend. “I don’t think I realised how close we were as friends. I think I miss that the most,” he says, adding that the extended family’s openness about the singer and his death “helped me with grieving the most. They have a really strong pragmatism about life and dealing with things when someone has passed away. They talk about it more frankly than I had expected.”

He also worked through his grief by collaborating with Gurrumul’s family on the touring stage show Bunggul, in which dancers, songmen and a didgeridoo player from Elcho Island perform to a recital of the singer’s final album. The critically acclaimed piece, co-directed by Ganambarr, went to the Sydney, Perth and Adelaide festivals but COVID-19 meant seasons planned for the Darwin, Melbourne and Brisbane festivals were cancelled.

Ganambarr hopes Bunggul will eventually tour to those cities so the cast can “present the stories about the nature, the country, the animals that we (Yolngu) live by. We were giving that story back because they (audiences) were listening to his songs, but they never got the real story of where those stories were coming from.”

Hohnen says that working and touring with Gurrumul’s family had alleviated his nagging doubts about whether, as a non-Indigenous person, he had been right to take the singer’s traditional music into unexplored territory. “He was not a decision-maker so I would make decisions and then fret about (them),” Hohnen says. “But now having this new chapter of working with his nephews and uncles … I feel really happy that my judgment was good.

“I think we had to push the (musical) boundaries to have that impact.”

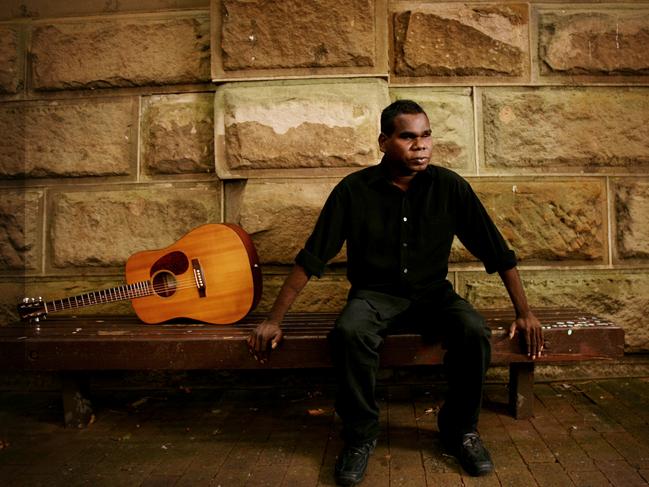

The man who persuaded Gurrumul to launch his solo career in 2008 — with remarkable results — was photographed for this article holding the performer’s first Martin guitar, which Gurrumul’s aunt “gifted to us before she passed away”. The location of the picture, Darwin’s Botanic Gardens, is also significant — it’s the site of the singer’s first solo show.

While some traditional Indigenous artists are caught between the conflicting values of the traditional and contemporary worlds, Hohnen says Gurrumul “loved both. He was very strongly cultural. He was confident because he knew all of his songs, all of his language, all of the lore. He had a complete life outside of mainstream life.”

Nonetheless, Gurrumul died in a Darwin hospital soon after he was found on a beach in Darwin in a fragile state. His death followed his decades-long battle with kidney and liver disease and hepatitis B.

According to Hohnen, the performer’s family was deeply upset by inaccurate claims that Gurrumul, who had missed dialysis sessions in the weeks before he died, was neglected. “He had been going to that beach for years. We would often visit him, take him back to hospital if he wanted to go. He was on dialysis and he hated dialysis … so that (the circumstances of his death) became a sensationalised moment.”

He says Gurrumul’s family was “highly aware” of his serious health issues. “He was sick — he got hepatitis B in his teens so his whole system was compromised from a really young age. So they knew from 10 years before that it was almost inevitable that he wouldn’t have a long, strong, healthy future.”

Had he lived, Gurrumul would have turned 50 in January. With more of the artist’s distinctive, ethereal music — described by one reviewer as “fraying the edges of the possible” — in the pipeline, Hohnen predicts that “Gurrumul’s legacy will last and be continued by his family. They see continuing what he started as being almost like their job.”

Ganambarr concurs that “it’s important to keep his music going to teach people more about Yolngu culture”, while Meher-Homji says: “It’s such a unique voice and he has so many fans. Elton John thought highly of him. Barack Obama did. Sting thought highly of him. His music has a connection on many levels with people, which is why we feel that the world needs to hear it.”