Michael Klim’s journey from the Iron Curtain to the top of the swimming world

Olympic swimmer Michael Klim charts the upheaval of his childhood, and reveals how one place – the pool – became a constant.

People assume my first memories are of grey Poland in the communist era, but the exact opposite is true. My earliest memories are of the heat and colour of Bombay, now Mumbai, because, while I was born in August 1977 in my father’s hometown of Gdynia, in Poland, my father was shortly after appointed as a trade attache to the Polish consulate in India, where we lived a relatively privileged expat life in a wealthy enclave, with a nanny, a housekeeper and a driver.

The expat community is very social so lots of parties take place. As recent arrivals from northern Europe, we’re not used to the heat. We spend all our spare time trying to cool off at the Breach Candy Club, which boasts one of the biggest saltwater pools in the world, on land adjacent to the Arabian Sea. My sister Anna and I spend many hours there, playing in the water and having swimming lessons. That’s where we first learn to swim under the expert tutelage of Mrs Bathena, who will become a family friend for life. Only 18 months older, my sister is my pathfinder, protector and constant companion. She’s always by my side. Whatever she does, I want to do, including learning to swim. The pool is the safest place for me because I am active and curious, climbing on things, falling off them, going to the hospital for stitches or, most memorably, sticking a piece of LEGO® so far up my nose that we have to go back to the hospital to get it out.

We are in Bombay for almost five years before my father’s term finishes and we return to his hometown of Gdynia, where he secures another position in a state-run trade company. Our name is Klim, but it should be Klima as it was in my grandfather’s day. It means climate or weather, which might account for my emotional volatility. But there was an administrative error when my grandfather Jerzy, a construction engineer and architect, joined the Polish Army as an officer before World War II. They accidentally left the “a” off his name on his identity card, so Klima became Klim.

When we return from Bombay, we move into a comfortable three-bedroom apartment in the north of the city. We’re an active family so we join the Arka Gdynia sporting club. At that point, Anna and I are both swimmers, but soon Anna will switch her sporting passion to tennis. I’m only six but I’m already a fairly good swimmer. In Bombay I’ve had the kind of exposure to swimming at a young age that is rare in Poland. So I’m ahead of the game here. But not at school. After the freedom of our expat life, school is a shock to the system. In India we have spoken mostly English in public, together with a bit of Hindi, so my Polish is not great. With my white-blond hair, tan from the Indian sun and imperfect Polish, I stand out. My speech is also affected by a lisp, due to a slight malformation in my mouth.

I undergo minor surgery to cut away the excess skin above my front teeth, and Mum and Dad send me to a speech therapist. The lisp improves significantly but never disappears entirely. It takes time, but eventually I find my feet. Meanwhile, Dad works for the State Foreign Trade Company as Head of Import, supplying a chain of hard currency shops, providing Western products like Toblerone and Johnny Walker. On his travels, he also buys us brightly coloured Western backpacks, which make us the envy of our schoolmates.

Generally, life is good for me. I’m protected by my parents from much of the harshness and deprivation that exist under communist rule. However, one day my mother goes shopping for groceries with our food tickets and comes home with broken ribs after a man elbows her to push in front in the queue to buy food. Still, we generally don’t want for much as Dad is a resourceful man.

Not long after returning from Bombay, Dad announced that he had to drive to the Polish–German border and asked me to go with him. We drove through the night and picked up a Phillips television that he had arranged to have delivered to the customs station at the border. Yet having too many Western contacts can get you into trouble in communist Poland. We assume our phone is tapped by the secret police. Dad’s job gives him access to international travel and foreign contacts. It is allowed, but he has to be careful and ensure he represents his company in the right way. Even so, he is regularly quizzed about his contacts. One of these “interviews” lasts for two days. We bounce between the freedom of the West and the restrictions of our home country.

In 1986, we are at school one day in April when we are all unexpectedly sent home. It’s the day of the Chernobyl nuclear explosion in neighbouring Ukraine. Once school resumes, we are called to the assembly hall and given a strange drink. Later we understand that it contains potassium iodide to prevent radiation sickness. The Polish government has a stock, but not enough for the whole population. The military, essential services and schools get priority until there is enough for everyone.

Despite the best efforts of the communist regime, the Solidarity movement continues to grow in strength and power as it campaigns for workers’ rights. We live through various crackdowns where curfews are imposed, arrests are made and tanks move through the streets. By 1987, my parents have had enough. All their parents – my grandparents – have died and we no longer have close family in Poland. They know what life is like in the West, and they can see a better life for us there. My father is offered a trade consultancy contract for 18 months in Germany through a business contact and that is our way out. When I’m nine years old, Mum, Anna and I pack and drive to the West German border, through Poland and East Germany, where Dad meets us for the rest of the drive to Hamburg.

Life is good in Germany. I can’t get enough of Western food – particularly the sweets. Before long, I am a chubby kid. Our parents’ first priority is to find a pool for me and a tennis club for Anna. School is a bit more intimidating because we don’t speak any German, but there are some other Polish kids around and we pick up the language quickly. One day, I end up in a fistfight after a group of kids makes fun of my sister. It’s short: I throw one punch and the ringleader goes down. I’m more surprised than he is, but my father is called to the school to sort it out. By nature, he’s a disciplinarian – that’s the Polish way of raising kids – and he’s concerned that I’ve lost my temper. From then on, he preaches to me that I must control my emotions and show respect for others.

Once again, swimming is my passport to friendship and acceptance. We join SG Hamburg swimming club, where Stefan Pfeiffer, already an Olympic medallist, is the star swimmer, and his father the coach. We can’t get over how beautiful the pool and the facilities are. I’m in Hamburg when I first become excited by the Olympic Games. It’s 1988, the Games are in Seoul and the German swimming team is strong, led by “The Albatross”, Michael Gross, who wins the 200m butterfly gold medal. Stefan Pfeiffer wins the silver medal in the 1500m freestyle behind the great Russian Vladimir Salnikov. We also have high hopes for Gross in the 200m freestyle, but it turns into a duel between Australian Duncan Armstrong and American Matt Biondi. That’s the race that fires my imagination. The German commentators are focused on the Gross–Biondi battle and don’t even notice Duncan flying down “Lucky Lane 6” to win. Their shock at the result makes for riveting television, as do the crazy antics of Duncan’s coach, Laurie Lawrence. I’ve been taping all the swimming finals on our VHS recorder and I watch them over and over.

I’m an instinctively competitive person – there’s nothing that I love more than chasing the swimmer in front of me. I’ve been to Berlin for a meet, racing kids much older than my 10 years, and I loved it. An idea pops into my head and fixes there. Maybe one day I could compete at the Olympic Games. I start to feel a sense of purpose about my swimming. I’m chasing that big dream, not just the feet of the swimmer in front of me.

Dad’s work contract in Germany is only for 18 months but he immediately starts planning the next move. Through contacts in Australia, he applies for a business visa to immigrate, but the process is long and slow and not completed by the time his German contract finishes. Mum and Dad hedge their bets by also applying for a Canadian visa, as my dad’s brother Paul has recently settled in Toronto. The Canadian visa arrives first so that’s where we go next. We don’t know how long we will be in Canada, and Mum and Dad don’t want to burn through our savings so they look for jobs to support us. Factory work is available, so that’s what they do, working long hours to provide for us.

Dad gets a job as a storeman for a medical supplies company and learns how to drive a forklift. The manual labour leaves him lean and fit. Mum is initially working on a food production line until she uses her engineering background to solve a problem on the line and is immediately promoted to the office. At the time, Anna and I don’t recognise the sacrifices they are making to find a better future for us.

When Mum and Dad are working, I take a train and a bus to reach training. Anna’s switched to playing tennis now, so I travel alone – often before dawn – in the cold, 20km across a city I don’t know, trusting in my fractured English to get me to the pool. By now I’m pretty adaptable and independent, and I’m dedicated to my sport. I may look different from the other kids, I may sound different, I may be in a foreign country, but at the pool I am comfortable.

That has been one of the few constants in my life, and it’s the one place where I know I can shine.

After nine months in Toronto, Dad comes home one day and says we are moving to Australia. His business visa has come through. I wasn’t aware that this was even in the plan, and I don’t know much about Australia. Kangaroos and Duncan Armstrong – that’s about it. My sister Anna knows a bit more. An Australian television series called Return to Eden aired while we were in Poland, and Anna was obsessed with everything about it. I was too young to watch it, but she’s very excited that we’re going to Australia.

We arrive in Melbourne on 30 April 1989, when I am 11. Dad’s new business partner picks us up from the airport and takes us straight to Pizza Hut for a meal before dropping us at a motel at the end of Brighton Road in Elwood, near the bay. Melbourne seems vast, but like a huge country town. In our motel room, I turn on the TV and there’s another weird sport – big guys wearing singlets and chasing an odd-shaped ball around an oval field. We’re not in Canada anymore.

This is an edited extract from Klim by Michael Klim and sports journalist Nicole Jeffery (Hachette).

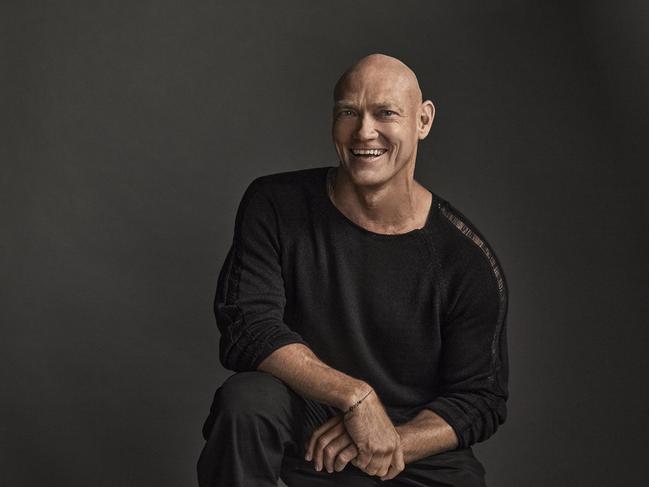

About Michael Klim

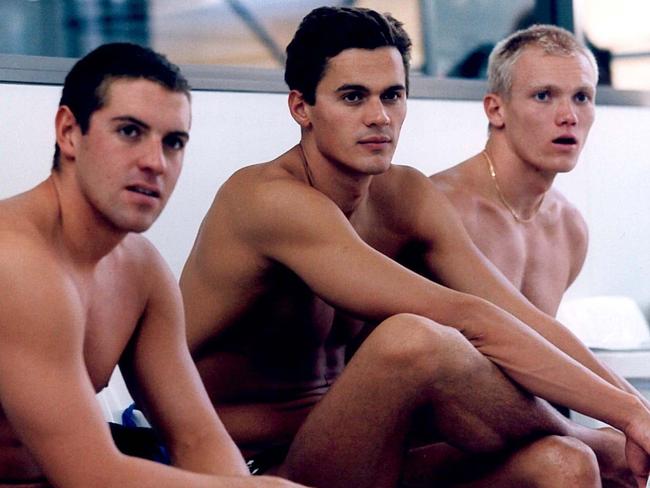

Michael Klim competed in three Olympic Games for Australia and won six medals, including two gold. At the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, he unleashed a world record in the 4 x 100m men’s relay victory, to assist Australia to gold. He has won 11 Commonwealth Games medals and 26 World Championship medals, and has held 20 aquatic world records.

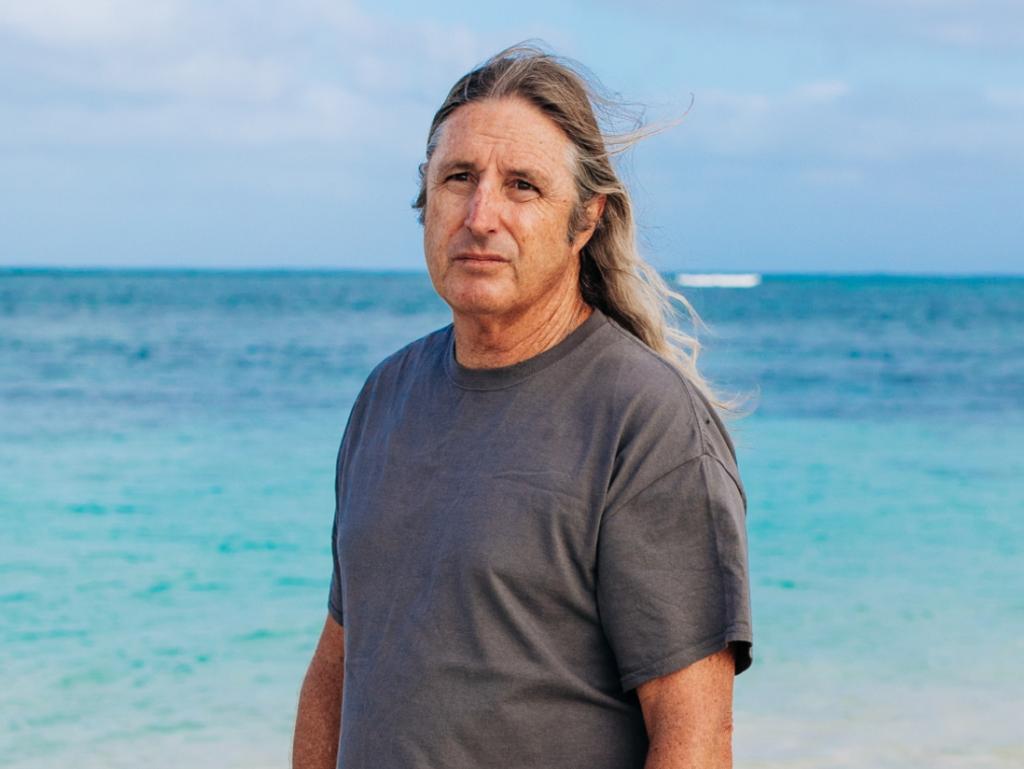

Michael is today an entrepreneur, having started several successful companies, among them MILK. Since 2020, he has lived with a rare autoimmune disorder, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). He has established the Klim Foundation to provide support to sufferers and champion the search for new treatments. Michael lives in Bali with his partner Michelle Owen and three children, Stella, Rocco and Frankie.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout