From Classical to Romantic, a changing landscape

The popularity of landscape artists waxed and waned throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but many are now rightly revered for their craft.

Classical landscape reaches its apogee in the work of Claude Lorrain, and yet there was never a single model of the classical, let alone any kind of prescriptive doctrine, for the genre was almost ignored by the theoretical writers. Even Claude’s work was very diverse, since he was as well known for his seascapes, or more exactly views of ports, as for his pastoral landscapes. Over the course of his long career too, Claude’s style evolved, becoming more meditative, more concerned with themes of destiny, as we see in his last painting, Ascanius and the stag of Sylvia (1682), and with the ineffable stillness of being, so mysteriously evoked in Noli me tangere (1681).

In fact, the 17th century left no fewer than four canonic models or varieties of landscape for later generations. As well as Claude, there was Poussin, with his more rational, architectonic and philosophical vision; Gaspard Dughet, Poussin’s brother-in-law and pupil, sometimes known as Gaspard Poussin, who tended to paint mountainous scenery in a more romantic vein; and finally the Neapolitan, Salvator Rosa, who preferred even wilder and more remote views.

And this is not to mention the great Dutch landscape painters of the same period; but Dutch painting was outside the mainstream, except for those Dutch artists who joined that mainstream by moving to Rome. In the second half of the 17th century, Paris became increasingly important because of the power, wealth and influence of Louis XIV, but Dutch art was barely noticed by the French either until very late in the century, when Roger de Piles, by then one of France’s leading authorities on art, was caught spying in Holland and spent some of the time he was detained by the authorities in becoming acquainted with the local traditions.

Roger de Piles thus becomes the first author in the dominant Italo-French mainstream to mention Rembrandt, in a famous table, the Balance des peintres (1708), in which he evaluates the most important artists of the modern tradition according to their ability in composition, drawing, colour and expression. But even he doesn’t mention Vermeer, whose tiny output was all but forgotten even in Holland and who would not be rediscovered until another French intellectual, Theophile Thore-Burger, became fascinated with him in the 19th century.

Roger de Piles was also one of the first authors to offer some theoretical views on the genre of landscape, in his Cours de peinture par principes, a collection of lectures delivered at the Academy and published in 1708. But even he did not include the Dutch landscape painters in the Balance des peintres. They would not be rediscovered, as we shall see, until the Romantic period. Nor for that matter did De Piles mention Claude Lorrain, who was comparatively forgotten by the French, though held in the highest esteem by the Italians and the British.

Dutch landscape is usually divided into an earlier and a later generation, which can be clearly seen in the difference between the work of Salomon van Ruysdael and his nephew, Jacob van Ruisdael (who chose to spell the family name differently). The work of the former, painted in the years after protestant Holland gained its independence from Spain, revels in the specificities of the Dutch landscape: low horizons, water everywhere, billowing clouds reminding us of the constant rain. The latter looks for more dramatic views with greater elevation, stronger tonal contrasts and a moodier, more intense atmosphere.

All Dutch landscape is thus based on topographical views of real places in The Netherlands, which distinguishes it from the classical tradition in which compositions may include elements of views and real motifs, but are ultimately imaginary, universal and poetic. This is why the pseudo-Marxist argument, a cliche of art-school teaching, that landscape is about the capitalist sense of property, is profoundly misleading: classical landscape is about the sense of nature permeated with cultural memory, while Dutch landscape is also about a sense of nature, but infused with a spirit of national pride. Neither has anything to do with the idea of private property.

Landscape had acquired considerable importance in 17th-century Rome and was eagerly collected by the richest and most noble patrons, yet it still had little or no official status in art theory. This state of affairs was aggravated by the fact that the first modern Academy, inspired by proto-academies that had existed in Italy for a century, was founded in Paris in 1648, becoming a centre of theoretical and critical debate in the 1660s and 1670s.

Even though three of the greatest contemporary landscape painters, Claude, Poussin and Gaspard, were French, they all lived in Rome and the genre made little impact in France itself; Poussin was venerated, but as a history painter. Consequently, the discussions of the Academy confirmed, by omission, the non-status of landscape.

It has been said that the 19th century begins with the Congress of Vienna after the fall of Napoleon in 1815, and ends with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. In the same way, we can say that the 18th century begins with the death of Louis XIV in 1715. The last decades of Louis’s reign had been dominated by relentless and exhausting war with protestant enemies led by William of Orange and then the Duke of Marlborough. After his death, France was exhausted and taste turned from the grandeur of Versailles to the Rococo playfulness and melancholy of Antoine Watteau, who drew inspiration from Flemish landscape to create a sub-genre epitomised by the Voyage to Cythera, which should more correctly be titled Return from Cythera (1717).

Later Rococo artists like Boucher turned landscape into a decorative formula with conventionalised pastoral themes that belong to the world of Meissen figurines and ultimately express themselves almost as a kind of performance art in the artificial dairy of Marie-Antoinette at the Hameau in the park of Versailles. In Italy, classical landscape continued to be practised by Italian and northern painters resident in Rome and elsewhere, including Jan Frans van Bloemen, known as Orizzonte for his love of horizons. But a century after the great masters of classical landscape — and just as happened time and again in China — the tradition began to lose its vitality and freshness of inspiration.

By the middle of the century, however, art theory and academic teaching had finally caught up with landscape. With the rise of Neoclassicism and a new spirit of seriousness, teachers such as Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes began to instruct their pupils to paint oil studies of real scenes from life as the best way to learn to paint landscape.

Of course, artists had drawn from nature long before this: Leonardo, Duerer, Poussin, Claude and many others had drawn in charcoal, ink and wash and even watercolour. What they had rarely done was to use oil paint en plein air. This was partly because elaborate and large-scale landscapes obviously cannot be painted outdoors, but even studies were harder before the invention of paint tubes in the mid-19th century. It was, in effect, necessary to go out with a preset palette and prepared panels or sheets of card.

The revival of Neoclassicism, after the post-Sun King holiday of Rococo, coincided significantly with a return to Rome as the centre of contemporary art. That role had been usurped for almost a century by Paris and Versailles, although the French Academy had set up a branch in Rome as early as 1666, where the most talented pupils of the Academy would be sent effectively for postgraduate studies. Since 1803, the Academie de France a Rome has been based in the magnificent Villa Medici at the top of the Spanish Steps.

So even when Rome was no longer the centre of contemporary art, it remained the capital of postgraduate art teaching, and every other significant country in Europe followed France in setting up schools in Rome. The American Academy in Rome was founded in 1894. Australia does not yet have its own school in the city, but Australians can apply to stay at the British School at Rome, where you find yourself surrounded by a unique combination of artists, archaeologists and classical scholars.

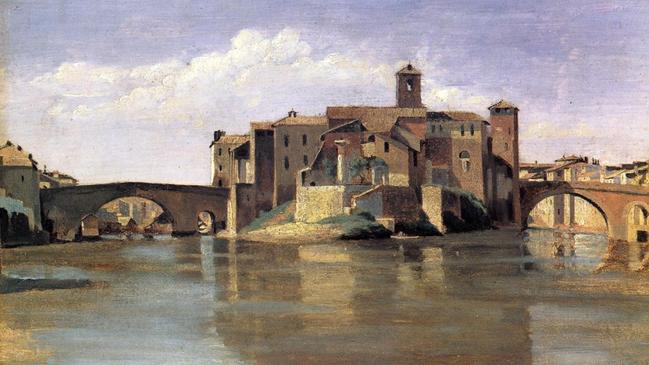

Rome also became the centre for the new practice of plein-air oil painting, and this phenomenon has been an active field in recent art-historical research, resulting in a number of survey exhibitions and scholarly catalogues on the work of French, British, German, Scandinavian and American artists in Rome in the later 18th and early 19th centuries. One of the most interesting exhibitions mounted at the AGNSW in recent years was a survey of 18th century plein-air painting (2004) filled with surprisingly fresh oil studies on paper.

What is really remarkable is that for some years, plein-air painting seems to have been something that young artists practised when they were in Rome. For northern art students, the bright sun and fine weather were clearly a delight, but there were also important social and cultural dimensions to the practice: socially speaking, young artists often went out in groups of friends on painting expeditions. And from the cultural point of view, the sites they painted were not chosen at random but were part of what became a regular itinerary in and around Rome: every location was imbued with historical significance and often overlaid by associations with the great artists who had painted or drawn there in earlier generations.

It was not easy to replicate these special conditions when a young man returned to London or Paris or Copenhagen, but gradually plein-air painting was acclimatised in the north too. In France, J.-B. C. Corot played an important role in this and he will be discussed on another occasion. Soon it was practised even by artists who had not left their own country, including John Constable, whom we will also talk about at greater length.

Among those who did go to Italy, many artists returned with notebooks filled with studies and sketches, which they could continue to draw on for years to come. John Glover, who travelled to Italy in 1818, and who was the first established artist to migrate to Australia, arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1831 with sketchbooks full of Italian subjects that he continued to paint for export in the years that followed. Interestingly, artists such as Glover had a longer British tradition of watercolour to draw on, and generally preferred this more portable medium for plein-air studies.

The most prolific of such visitors to Italy was JMW Turner, who made numerous trips to Italy, during which he produced countless drawings and watercolours. His greatest inspiration was Claude Lorrain, and particularly Claude’s harbour scenes that brought together Turner’s favourite elements of water and light, which as we shall discuss next week he was to turn into visionary images of mystical communion with nature.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout