From a quiet place of stillness: David Noonan exhibition review

The title of this exhibition comes from the writings of a 14th century Japanese Buddhist monk whose theories suggest that enjoyment should be based on our own state of inner calm.

David Noonan: Only When it’s Cloudless TarraWarra Museum of Art, until July 10

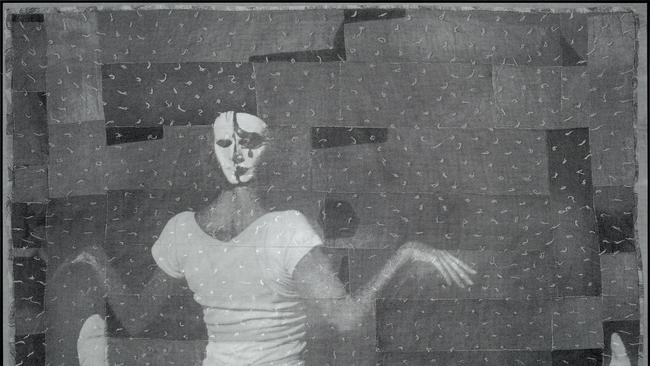

There is always something enigmatic, disconcerting and melancholy about old photographs of performances. An actor is caught in the middle of a speech, but we don’t know what he was saying; a dancer is in a striking attitude, and we cannot understand the flow of movement that would explain the meaning and direction of this isolated moment.

Such pictures may seem, to those who were present, to capture something quintessential about the performance, and yet they also represent things that were not really visible to the audience, who were caught up in the emotion of the actor’s speech, not looking at the striking pattern his figure made against the window behind him, and who were absorbed in the dancer’s movement, not a frozen posture produced by the artifice of the camera.

Later, when we have forgotten the occasion, the performance and even the actors, when the pictures themselves have become memories adrift in time, memories that were never ours in the first place, such images can become even more mysterious and poignant, like unintelligible fragments of an ancient text. We know that they are the vestiges of meaning, but we cannot pin down what that meaning was.

Especially evocative are images of non-naturalistic forms like dance, mime, or perhaps above all masked theatre, as practised in Ancient Greece, in Classical Indian and Javanese dance drama, or in Japanese Noh drama. The very word persona originally meant a mask in Greek – just as a “hypocrite” was an actor – and anyone who has watched classical or modern masked theatre will have been struck by the tension between the expressiveness of voice or corporeal movement and the immovable stillness of the painted features.

The first bay of David Noonan’s exhibition at TarraWarra plunges us into this intense yet strange and even disturbing world of performance, the domain of Dionysus, god of intoxication, illusion and altered states of consciousness. He is the liberator, as Nietzsche says, but he is also a chthonian deity who draws the sources of perennial life from the shadowy domains of death and the underworld.

The first image that faces us suggests the masked chorus of an ancient play, although I can’t think of one that matches the costume unless it is perhaps the Ichneutai, a fragmentary satyr-play by Sophocles rediscovered just over a century ago at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, where the Greek verb kynegetein, used several times, may have suggested doglike masks for the eponymous trackers. The two seated figures, one apparently speaking or explaining something while the other turns to listen, epitomise the strangeness of lost meaning; the image is vivid, memorable, specific and yet unfathomable.

Next to this is another of Noonan’s most striking found images. This large version is in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat – his native town – but the photographic source itself is used several times again in smaller works. It is easy to see why: this picture combines two things that would each be unusual and even disconcerting on its own, but which in combination produce a kind of overload that stops us in our tracks. Even after we understand rationally what is represented, our normal habits of perception and visual interpretation refuse to process this as an intelligible or coherent phenomenon, and so we are left with it as something that will not go away, like a Zen paradox. The original photograph showed a performer sitting on the ground, and the first unusual thing about it is that he is seen from behind, seated in a position of lateral splits that is so impossible for most of us that it seems unnatural; the extreme athleticism of this posture is contrasted with the limp arms, like a bird’s wings. But even this, if we imagine it without the other element, would hardly arrest our attention.

The thing that is really disturbing is that while the body has its back to us, its face seems to declare the opposite, looking straight towards the viewer. And because we attribute more importance to the face than to any other part of a body that we encounter in the world, we are deceived into assuming that the figure is looking at us, which then makes the body seem impossible and paradoxical.

The answer, of course, is that we are looking at a performer, presumably a mime artist, wearing a mask on the back of his head. And this brings us back to the complex and even demonic associations of masks, as they appear in ancient sarcophaguses, or in paintings by Titian and Poussin inspired by ancient iconographic sources, once again linking the Dionysiac worlds of theatre and the afterlife. And faces on the back of a head have the most sinister associations, from Japanese ghost stories to Harry Potter.

The third image in this first bay is less obviously disconcerting but like the Nolan exhibition I reviewed at TarraWarra a few months ago, it reminds us that the meaning of a work of art is inseparable from its process, just as the meaning of a poem is inseparable from the precise words the poet has chosen to use, and the metrical, phonetic and figural techniques employed. Similarly, it is not enough merely to find and reproduce a few odd images; they must be transformed and reconstituted as artificial objects.

Noonan has done this primarily through the process of screen-printing. This is not inherently a high art medium, and has none of the linear or tonal sophistication of either etching, aquatint and other intaglio processes, or woodblock and wood engraving. It is an aesthetically limited medium, suitable for printing posters on a large scale, and reproducing photographs as a matrix of dots of different sizes. But it serves Noonan’s purposes, as, in a different way, it served Warhol’s.

Dissolving the photographic image into dots – smaller and sparser for light areas, larger and denser for dark – undermines its solidity and apparent factuality, reducing it to a floating and unstable appearance. Black and white already removes much of the materiality of the images, leaving them as disembodied shadows of experience, but the reduction to dots makes these shadows seem even more artificial and elusive.

The screened images are printed on canvas, but not in a straightforward way. Noonan has made several different screen prints of the same image, using different light exposures, and then cut these into strips and collaged them together – visibly gluing one over the other, leaving the edge with its cut threads exposed. The clearest effect of this process can be seen in the face of the young man on the left of the first bay.

The central strip of his face has been printed as though overexposed. The boundary is visible on his forehead, so that larger and denser dots on the left suddenly meeting smaller and lighter ones; the result is that the highlights on the centre of his face are so overexposed – the dots are so tiny – that all definition is lost and the area almost appears blank. In addition, all three of these large screen-printed works are flecked with random but regularly-spaced white squiggles, as though dust had got into the enlarger; this relieves the inert quality of the dark areas and covers the work with an overall decorative pattern.

A number of works are produced as Jacquard tapestries, also in black and white, and here too the soft and carpet-like surface of the tapestry has the similar effect of abstracting images and turning them into semi-indeterminate patterns of light and dark.

The exhibition also includes a series of smaller prints exhibited in the corridor outside the main exhibition spaces, and notably a bay of medium-scale pieces based for the most part on Japanese theatre with, for example, a Kabuki actor looking into the mirror and painting on the curved and sinister mouth of a demon, and another, already made-up for a female role, pausing to smoke a cigarette before putting on his wig and costume.

In the middle of the exhibition is a work consisting of images of Japanese performance and other related motifs screen-printed onto canvas and mounted on vertical aluminium sheets, in turn attached to steel stands. The images are effective, but the scale and evident cost of the industrially fabricated stands seems rather out of proportion. There is a principle of economy in art, and it is always preferable when more is achieved with less than the other way around.

The title of this work, however, has also been adopted as the title of the exhibition: as we are told, it comes from the writings of Yoshida Kenko, a 14th century Japanese Buddhist monk, who tells us that we should not look at the moon “only when it’s cloudless”. He is presumably referring to the genre of earlier Chinese writing which liked to catalogue delightful moments, like reading an ancient scroll with learned friends, or drinking tea while gazing at the full moon on a cloudless night.

Kenko’s point – in a true Zen spirit – is that we should not only enjoy the moon on a cloudless night, because our enjoyment should not be based merely on the happy chance of ideal viewing conditions, but more profoundly on our own stillness of mind, our own state of inner calm, detachment from desire and presence.

No doubt this is the spirit of the final work in the exhibition, a video work shown on a grid of six screens in the final room of the gallery. More precisely, it appears to be a work shot on 16mm film and then transferred to a digital form for exhibition in this format.

At first sight, it seems to be an animated collage of different black and white images that all move steadily and at the same pace from right to left for just over 20 minutes. The imagery used varies from random pictures that might be travel snaps or material from books to others that feel much more personal, like childhood photographs or shots of an old family home. As the images progress, they are washed over by veils of yellow – striking when everything else is black and white – or occasionally billows of black.

The work is titled Mnemosyne, after the Greek goddess of memory, mother of the nine Muses. But the real subject of the work, I suspect, is the practice of meditation, which many people today do for 20 minutes. The sequence we witness is like a simulation of the meditating mind, in which images or vestiges of images float past, sometimes in detachment, sometimes in a happy and peaceful state, and sometimes with moments of sadness or regret. In this sense the work is indeed about memory; but not the effort of recollection, rather the involuntary resonance of past experiences in a mind that is settled into stillness.

C

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout