Forget MONA. Try this Hobart museum instead.

There is more to the Tasmanian capital’s art scene than David Walsh’s MONA, and there are rich rewards for those who seek it out

There used to be, and perhaps still is, a sign in the Long Bar at Raffles: “While at Raffles, why not visit Singapore?” There should be something like that at MONA, reminding visitors that Hobart is also worth a look, not to mention the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. For while MONA has transformed Hobart as a tourist destination, it also tends to monopolise attention and obliterate all other attractions in the city.

This is not surprising when you consider the combination of the museum itself and its site. The building, excavated into the cliff, immediately appeals to our atavistic fascination with – inseparable from our dread of – dark places, caves, labyrinths and even the underworld. And this setting was perfectly matched to David Walsh’s interest in themes of sex and death, from ancient Egyptian sarcophaguses to contemporary art.

At the same time, the underground museum is complemented by the open hilltop above, where on a fine day there is no better place to have lunch in one of several eateries designed for different tastes and budgets. Meanwhile, thanks to the policy of free entry for Tasmanians, the bar down in the depths of the museum is well-frequented by people not noticeably interested in art.

Finally, there is the private ferry, naturally painted in naval camouflage, which makes a very pleasant river cruise on the Derwent and also has the option of upgrading to the Posh Pit in the prow of the vessel where guests are spoilt with cakes and sparkling wine. The very fact a visit to MONA is an excursion, a day out, an opportunity to eat and drink, gives it an advantage over any institution in the city itself, whose main attraction is its collections; and indeed MONA’s galleries were much less crowded than the other facilities.

The reason to visit the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, on the other hand, is to see the art, or rather the many displays, for, in fact, TMAG is one of those institutions, common in the 19th century but rare today – except at the newly combined museums of the University of Sydney – that is museum and art gallery.

TMAG thus has much more than pictures: there are scientific and maritime displays, since Hobart is the home of Australian Antarctic and Southern Ocean studies. There is fascinating natural history material, too, including a large room of animal specimens, mostly representing taxidermy of a high standard. A contemporary work is the large inlaid and painted chest known as The Tasmanian Pavilion (2021), by Michael McWilliams and Peter Collenette, a piece of quasi-scientific furniture that recalls the Macquarie Chest (c. 1818) and more recently the Newcastle Chest (2010).

From an art-historical perspective, though, TMAG holds some extremely important works of early Australian painting, as well as furniture and other artefacts of the early colonial period. The most notable paintings are by John Glover (1767-1849), who arrived in the colony in 1831, at the age of 64, the first artist to come to Australia with an already established reputation in Britain. Three of Glover’s sons had arrived in Tasmania in 1829; he spent the first year or so in Hobart, where he painted the view of Hobart hangs in the State Library of NSW galleries. Then in 1832 he acquired a large land grant of more than 1000ha, which he subsequently extended to almost three times that size; he had brought out English shrubs and songbirds, and the former can be seen in the beautiful and almost visionary painting of his house and garden (1835) – one of the most memorable paintings of the 19th century in Australia – in the Art Gallery of South Australia.

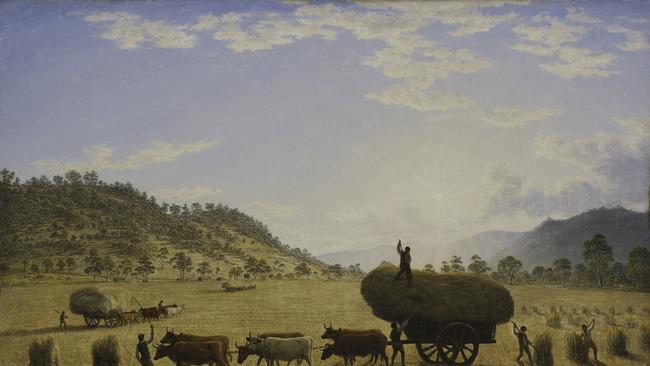

A second painting by Glover that has a similarly visionary quality is in the Hobart collection: My Harvest Home (1836). The expression refers to an ancient British and Celtic ceremony marking the last day of harvest, and, indeed, the artist noted on the back of the picture that it was started “the day the harvest was all got in”.

In the foreground, a dray drawn by a team of six oxen stands in striking contre-jour against the golden fields, silhouetted by the rising sun in the distance. Four convict servants, identified by their red vests, are loading the last bundles of wheat and preparing to set off back to the farmhouse, following two wagons that are on their way on the left of the picture. Glover’s painting is an expression of thanksgiving, a celebration of life and fertility in a land that had never been tilled or sown until he settled there.

Of course, the Indigenous people had lived in this country in a very different way for thousands of years, but by the time of Glover’s land grant, they had gone. The Black War, which had lasted from the mid-1820s to 1832, had concluded with the resettlement of the last of the Indigenous population to Flinders Island in the Bass Strait. Truganini, the most notable of these survivors and the last fully Indigenous representative of the old Tasmanians, died in Hobart in 1876.

Anyone seeking to learn more about this period could consult the catalogue of The National Picture, an important exhibition jointly mounted in 2019 by TMAG and the NGA. There is also an excellent account of these tragic events in Nicholas Clements’s The Black War (2014). Clements does not shy from any of the appalling things done to the Indigenous population, but he also brings the settler community into sharper focus, revealing the wide range of attitudes towards the native peoples, and reminding us the settlers on the front lines of conflict were themselves largely wretched emancipated convicts trying to eke out a living in harsh circumstances, while subject to attacks of great ferocity.

A little painting of an incident from the last, but most desperate years of the conflict, Aborigines attacking Milton Farm, Great Swanport, December 14, 1828, gives a vivid idea of how terrifying it would have been for a single settler to find himself surrounded by a dozen men armed with spears. He has a rifle, but may have fired it and seems now to be relying on its bayonet to defend himself.

We actually know quite a bit about this little picture, and David Hansen’s essay A Raid, published in Griffith Review (#39) can be found online. The young man with the rifle was John Allen (no relation), who had obtained in 1826 a 160ha land grant near the Cygnet River, and had already suffered one Aboriginal raid, early in 1828 and soon after reaping his first harvest, which was burnt by the attackers. On this second occasion, Allen not only survived against all odds, but executed a detailed sketch, which became the basis of this painting (1833) by an unknown provincial artist, perhaps in England.

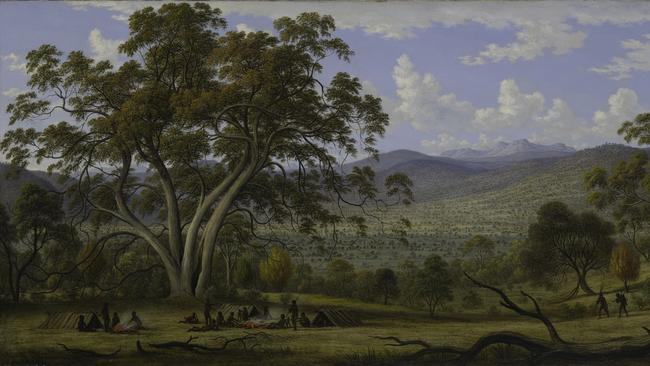

Glover – who had no experience of the conflict – was sympathetic to the Aborigines, or perhaps nostalgic for the idea of innocent natives living close to the state of nature. Thus he imagines them in lands from which they had long disappeared – perhaps using sketches he had made of NSW Aborigines who worked on his neighbour John Batman’s property – in another picture of his property, Mills Plain, Ben Lomond (1836). They gather, on the left of the composition, around a cheerful fire, with children playing among the adults.

Another picture of great importance to Australian art history and, indeed, to Australian history, is the so-called National Picture mentioned earlier. This painting is primarily significant as documentation of the mission of reconciliation to the Aborigines led by George Augustus Robinson, and which eventually led to the few survivors of the Indigenous people agreeing to being resettled on Flinders Island.

It is also important, however, as the masterpiece of Benjamin Duterrau, a painter of limited ability but high ambitions. Duterrau was not merely influenced by the academic tradition, but even more specifically by the French academic tradition. Thus he conceives of The Conciliation (1840) as a history painting, and potentially a great one, since he considers the reconciliation of native and settler as an epoch-making event in the history of the nation.

But he is also fascinated by the concept of expression, a fundamental principle of classical painting, but one that was given a somewhat narrow and mechanistic interpretation in the art and theoretical work of Charles Le Brun, the official painter of Louis XIV. Thus Le Brun’s early masterpiece The Tent of Darius (1661) was conceived from the outset as an anthology of different expressions, and many of the heads were used as illustrations for his lecture on expression at the academy a few years later, and subsequently published.

This collection of expressive heads clearly made a strong impression on Duterrau, and he similarly conceives of The Conciliation as an anthology of different expressions. If this were not clear enough from the work itself, the artist modelled reliefs of the main heads in clay, which were then cast in plaster and painted to look like bronze.

Exactly in the spirit of Le Brun’s repertoire, the heads are meant to represent Attention, Anger, Surprise, Incredulity and Suspicion. As I pointed out some years ago, the demonstration that basic human expressions could be found in these unfamiliar features was an implicitly humanistic assertion that all people share the same emotions and feelings.

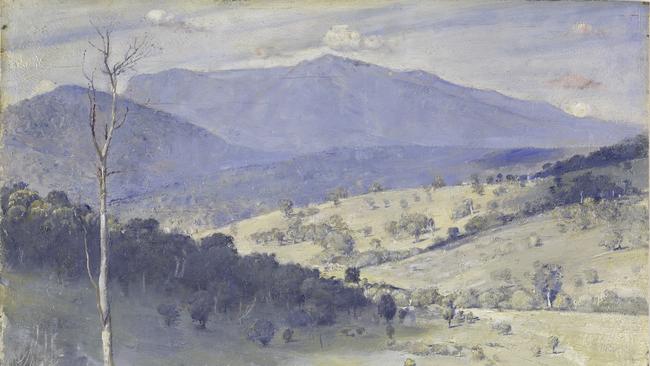

There are many other important landscapes in this collection, including one of W.C. Piguenit’s most impressive canvases, A Mountain-top, Tasmania (c. 1886), a late expression of the sublime spirit of romanticism, while Von Guerard’s View of Hobart Town, with Mount Wellington in the background (1856) is more lucid, airy and dispassionate.

Further views from the latter part of the century include Tom Roberts’s Morning on the Hastings River and Sydney Long’s The River – both from 1896, as well as an early landscape by Hugh Ramsay, Mount Wellington, Hobart (1897), much the same view painted earlier by Von Guerard.

But what is particularly interesting is to find a much later picture by Tom Roberts titled Glover’s Country (1929), and which even seems to recall some of the lightness and spareness of Glover’s style. The title is noteworthy because at the height of the Heidelberg movement, from 1885 to the end of the century, painters such as Roberts and Streeton seemed to recognise no predecessors except for Abram Louis Buvelot, immediately before them. This attitude led to the general assumption among their followers that Australian painting had begun with Heidelberg. And yet this painting suggests that by the end of his life, Roberts had begun to look at the formerly despised colonial painters, and to understand them as the true beginning of an Australian tradition of painting.

.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout