Eyes on the Prize

In his annual review of the Booker Prize shortlist, James Bradley considers the six novels in contention.

Sometimes you feel like the world is trolling you. A month ago, on the eve of the announcement of the shortlist for this year’s Booker Prize, I had read eight of the 13 books on the longlist. I was also feeling reasonably confident about the shape of the final shortlist. Of the eight I’d read, several were interesting and stylish but seemed unlikely to make the cut. This included Oyinkan Braithwaite’s sharply observed but relatively slight satire of Nigerian society, My Sister, the Serial Killer; John Lanchester’s intriguing exercise in dystopia, The Wall; and Kevin Barry’s mordant but stunningly well-written portrait of two ageing Irish gangsters, Night Boat to Tangier.

Two more — Valeria Luiselli’s hugely ambitious but oddly lifeless Lost Children Archive and Deborah Levy’s characteristically intelligent and subtle exploration of memory and loss, The Man Who Saw Everything — seemed like possible contenders for shortlisting.

And three others — Bernardine Evaristo’s chronicle of female experience, Girl, Woman, Other; Jeanette Winterson’s riff on gender, artificial intelligence and Mary Shelley, Frankissstein; and Max Porter’s gloriously inventive Lanny — seemed like shoo-ins for the short list (and in Lanny’s case, a clear contender for the prize itself).

But when the six-novel short list was announced, all that fell apart. Only Girl, Woman, Other made the cut, while all five of those I hadn’t read moved into contention for the prize.

At first it seemed a confusing selection, and not just because most of the books I’d assumed were frontrunners were missing. I’d held off reading Quichotte because, quite frankly, it sounded dire: Salman Rushdie reworks Don Quixote in Donald Trump’s America? Kill me now. Likewise, I’d let Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities slide because I’d been a bit underwhelmed by his first novel, The Fishermen, which was shortlisted in 2015.

While I was eager to read Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments, I knew almost nothing of Elif Shafak’s 10 Minutes, 38 Seconds in This Strange World. And while Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport sounded intriguing, the sheer 1000-page scale of it was a lot to take on.

Yet, as I worked my way through the short list, my respect for the judges’ choices grew. All of the books selected speak in interesting and sophisticated ways to experiences that are often marginalised, in particular those of women and migrants. And several — in particular Ducks, Newburyport and Girl, Woman, Other — are interestingly experimental in their approach to the novel as a form.

Of the six there is no question The Testaments has attracted the most attention.

This sequel to Atwood’s now-classic 1985 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, picks up 15 years later and explores not just questions of complicity and resistance but also the slow fall of Gilead, the theocratic dictatorship at the heart of both books.

Like its predecessor, The Testaments is related as a sort of future history, derived from the recently uncovered testimonies of three women who lived through the events it describes.

The first, Lydia, is one of the Aunts from the first novel. The other two are teenagers: Agnes, daughter of one of Gilead’s commanders, and Daisy, a teenager living in Toronto.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given Atwood’s larger interest in female cupidity, it is Lydia’s voice that is the most compelling.

Lucid, witty and entirely undeceived, her account is unsettlingly seductive, but also troubling for the same reason. However Atwood’s success in capturing Lydia’s voice is undercut by the voices of the two teenage girls, neither of whom ever comes to life in the way Lydia does.

And although The Testaments is never less than sleekly compelling, it loses impetus somewhat in its final sections. But these are quibbles. For while it may not bear comparison to Atwood’s very best work, The Testaments is a work of remarkable fluidity and moral intelligence that is lent life by its author’s coolly amused gaze and keen eye for human frailty.

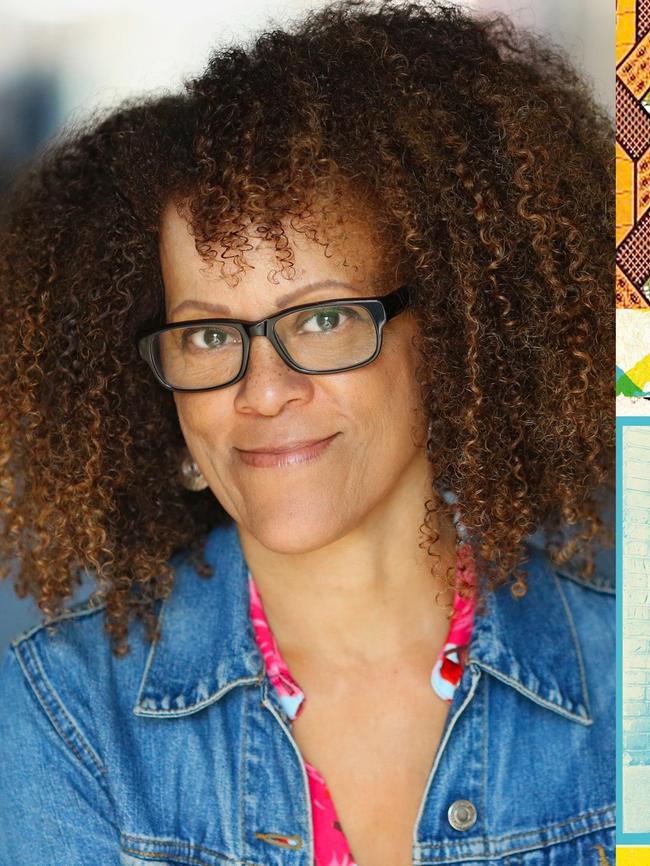

Of the remaining five books, three are also focused on women’s lives and bodies. The first, Evaristo’s marvellously alive Girl, Woman, Other, unpacks the interconnected stories of 12 very different women across three generations.

In earlier novels such as Mr Loverman, Evaristo explored the complexities of the African diaspora. That interest is replicated in Girl, Woman, Other, whose characters all inhabit complex identities: some mixed-race, some transgender, others immigrants or children of immigrants negotiating new class allegiances.

Written in a free-flowing, deconstructed style that inhabits a space somewhere between prose and poetry, Girl, Woman, Other vividly illuminates this cross-section of lives, leaping from one character to the next with remarkable dexterity.

Yet while there is considerable darkness and intergenerational tension, what distinguishes the novel is its generosity and insistence upon the particularity of each woman’s experience. Indeed the only real stumble is in the final section’s somewhat awkward attempt to bring its various narrative strands together.

Ellmann’s dazzling Ducks, Newburyport is both more domestic and more expansive. Weighing in at more than 1000 pages, it interweaves two narratives. The first, and more substantial, follows the day of an Ohioan woman; the other is about a mountain lion and her cubs.

Self-consciously modernist in its approach, the story is told, for the most part, in one, long, endlessly spooling sentence.

This sentence traces the looping, leaping thoughts of the woman at its centre, as she free-associates about baking, her late mother, her husband and children, Laura Ingalls Wilder, cancer, Trump, industrial waste, guns, school shootings and any number of other topics.

The effect is exhilarating, a wonderfully generative collision of the mundane and the marvellous that manages to capture something of the impossible complexity and interconnectedness of contemporary culture.

But the real pleasure lies in the writing itself, both in the human sections, distinguished by a wonderful sense of the performative orality of fictional prose, a delightfully off-kilter humour and a fascination with the surfaces of contemporary life, and in the mountain lion sections, which slip with remarkable ease into the world of the animal at its centre.

10 Minutes, 38 Seconds in This Strange World, by Turkish-British novelist Shafak, is built around a similarly elaborate conceit, in this case the idea that the brain continues to function for a time after death.

Liberated into this space, memory “staggers through a maze of inversions, often moving in dizzying zigzags”, like “a late-night reveller who has had a few too many drinks [and] … cannot follow a straight line”.

With this in mind the novel explores the life of an Istanbul sex worker, Leila, as she lies murdered in a vacant lot, leaping from her childhood in rural Turkey to her ill-fated marriage and life as a prostitute. Along the way it takes in stories of her closest friends and the moments their stories intersected with the tumultuous history of late-20th century Turkey.

The portrait of Turkey is unsparing but the anger about how women’s lives are deformed by politics and religion is tempered by a compassion for Leila and her unlikely friends. Similarly, the very real fury is given depth by a recognition that “grief is a swallow … One day you wake up and think it’s gone, but it’s only migrated to some other place … Sooner or later it will return to perch in your heart again.”

I have to confess I didn’t expect to enjoy Quichotte. Despite my admiration for many of Rushdie’s earlier novels, his work since Fury in 2001 has, to my mind at least, been hectoring and self-regarding.

Yet in Quichotte he seems to have regained a more even keel. A riff on Don Quixote, the novel follows two stories: the fictional tale of Quichotte, a pharmaceutical salesman in love with a reality TV star, and that of the second-rate spy novelist who is writing this novel about Quichotte.

As the novel shifts between the two narratives they begin to blur, as events in one reflect events in the other, and as they do the life of the Indian-born spy novelist is itself reimagined and remade.

There is a kind of delight to the metafictional play of Quichotte and, as the pasts of the various characters, real and imagined, are drawn into the light, it is often surprisingly moving.

Likewise the portrait of the modern world, and in particular America, in all its ugliness and wonder, is shot through with all the madness of what Quichotte describes as the “Age of Anything-Can-Happen”.

The result is not nearly as profound as it clearly thinks it is, and often seems a little like a catalogue of recent headlines (Racism! Trump! Rendition! Opioids!), but it is playful and assured and extremely entertaining nonetheless.

An Orchestra of Minorities, by Nigerian novelist Obioma, explores questions of displacement as well, albeit from a quite different perspective. Narrated by the chi — or spirit — of Nigerian chicken farmer Chinonso, it opens with a fateful encounter between Chinonso and Ndali, a young woman from a wealthy family who has decided to take her own life.

After Chinonso convinces her not to kill herself, he and Ndali become lovers. But when Chinonso is rejected by Ndali’s family he sells his chicken farm and travels to Cyprus to study business, a decision that leads to his ruin.

Although filtered through Chinonso’s chi, a device that grounds the novel in Igbo mythology and, by extension, Nigerian culture, the novel feels both exquisitely contemporary and oddly old-fashioned. For while its depiction of Chinonso’s alienation and grief in Cyprus speaks to the experience of migrants everywhere, the shape of the story has the clarity and inescapability of a Thomas Hardy novel.

To my mind the sections about Chinonso himself are far more engaging than the depictions of the spirit world. Yet there is no question Obioma’s wrenching depiction of Chinonso’s ruin offers a fascinating and original portrait of the world from which it draws its inspiration.

So which will win? It’s difficult to say. If I had to guess I’d probably say I suspect neither Quichotte nor 10 Minutes, 38 Seconds in This Strange World are likely to be in serious contention. While The Testaments would be a popular choice and still might win, it is an accomplished novel rather than a masterpiece.

Of the remaining three I suspect any might win, but if it were up to me, I would choose Ducks, Newburyport in a heartbeat.

For all that I adored Girl, Woman, Other, Ellmann’s epic novel is so electrically alive and thrillingly aware of the textures of our present moment it deserves to find the widest possible readership.

James Bradley is a writer and critic. His most recent novel is Clade.

The Booker Prize winner will be announced in London on October 14.

The Shortlist

The Testaments

By Margaret Atwood

Chatto & Windus, 432pp, $42.99 (HB)

Ducks, Newburyport

By Lucy Ellmann

Text, 1040pp, $34.99

Girl, Woman, Other

By Bernardine Evaristo

Hamish Hamilton, 480pp, $35 (NB)

An Orchestra of Minorities

By Chigozie Obioma

Abacus, 528pp, $32.99

Quichotte

By Salman Rushdie

Jonathan Cape, 416pp, $32.99

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World

By Elilf Shafak

Viking, 320pp, $32.99