Elastic conceits of Adelaide's Biennial of Australian Art

THE paradoxical title of this year's Adelaide Biennial, Parallel Collisions, is evidence of curator-speak's linguistic and logical flabbiness.

THE title of this year's Adelaide Biennial is a deliberate paradox, or more exactly an oxymoron: Parallel Collisions. As we learn at primary school, parallel lines are ones that do not intersect, or intersect only at infinity, which is for practical purposes never, and certainly beyond any dimension known or knowable to us.

Those familiar with Zen Buddhism may recall the form of a koan, a deliberate paradox - one of the best known being the sound of one hand clapping - which is used in meditation to force reason to confront the limits of the knowable, to reduce rational discourse to silence. Socrates, too, loved to push his interlocutors to a state of aporia, to a recognition of the contradictions underlying their commonsense view of the world. One of them, Meno, famously compared him to an electric eel that paralyses its prey.

But nothing can halt the discourse of contemporary art writing, in which paradox loses its potency and shrinks to the scale of a conceit that serves as the occasion of ever-renewed and ever-inconclusive logorrhoea. It is hardly surprising to find that this is the case with the introduction to the Biennial by its twin curators, a document apparently conceived as a manifesto but which is more a set of disconnected notes than the kind of programmatic statement or call to arms that is usually meant by this term.

It is full of the linguistic and logical flabbiness all too common in such writing, and reflects the lack of rigour and radical absence of critical thinking that reign within the world of contemporary art curators. Thus the authors speak of "excavating currents", perhaps another intended paradox that fizzes out as a hopelessly mixed metaphor, and they "incite" one of Walter Benjamin's ideas where we assume they mean "invoke". Clearly the texts have not even been edited for minimal coherence.

One of the gems in this document is a reference to "revelling in the liquid elasticity of the video medium". One can see what the authors are getting at, although the intended idea is hardly new or even surprising. But the expression "liquid elasticity" manages to be simultaneously a virtual redundancy and a logical ineptitude, for liquids, unlike gases, are for practical purposes not elastic or compressible. Flowing, yes; elastic, no: such is the basis of hydraulics. Coherent intellectual conceits need to be based on something more than this sort of spineless free association.

Obviously one can't really read this sort of writing, and one certainly can't engage with it in any intellectually meaningful sense, because there is nothing to engage with: the authors flirt with ideas rather than asserting or confronting them; curatorspeak is a sub-genre in which the implicit axiom is that everything can be anything, nothing is anything in particular, and that to swim in a state of uncertainty and boundlessness is proof of superior sophistication.

The labile, the liminal - those curatorial favourites - and the indefinable all have their place in art and thought, for the very core of experience is indeed ineffable. But that indefinable dimension of experience is successfully evoked only by works that are in other respects supremely articulate; it is the clarity and lucidity of the surrounding structure that guides the mind to the perception of what lies beyond the articulate. Thus the extraordinary intellectual architecture of The Divine Comedy leads to the sublime glimpse of what cannot be spoken or even fully understood at its conclusion.

In the world of contemporary art writing, the assumption is that we will get closer to the ineffable core by weakening the structures of critical reason and everything that pertains to such structures, including the rigour of chronology or the bounds of genre and convention. The result is a kind of writing that constantly asserts intellectual and even, extraordinarily enough, political concerns, yet remains amorphous and without intellectual purchase on the world. It is the writing that corresponds to a kind of aesthetic activity that has disconnected itself from civil society and now exists in parallel to it, like a theme park outside the fabric of the city.

The exhibition itself - much smaller than the massive hardbound and slipcased book would suggest - is in two main parts, the first in the temporary exhibition galleries and the second integrated into the 19th-century collection in the recently redecorated Elder Wing. The temporary exhibition section is conceived, we are told, like a tracking shot in cinema, where the camera travels through the space being photographed, moving from one thing to another without cuts.

This structure serves once again to reveal what seems to be an implicit principle of contemporary curatorship, namely to link displays and media as disparate as possible, rather than to assemble things that might be addressed by the viewer in the same sort of way as sculptures with sculptures or photographs with photographs. The intention, no doubt, is to keep viewers on their toes - contemporary curators are always concerned with what is good for us - but the perhaps unintended effect is to distance us from close engagement and lead us to see everything in a homogeneous and detached manner.

The first thing we encounter is a hugely enlarged photograph of a rioter throwing a rock, by Marco Fusinato, which epitomises the noncommittal attitude of such artists. This could be, after all, an Islamist fanatic or a democracy protester resisting a tyrant. And it is true that such distinctions can be blurred, especially in the Middle East. Nonetheless, the work is void of any ethical or political sense, concerned only to produce a certain effect. Much the same can be said of Fusinato's other work, whose title was adopted for the exhibition itself: nominally about the statistics that deluge us in the media, it is far more concerned with making an aggressive assault on the viewer's senses.

More impressive is a large room in which Jonathan Jones has set out an enormous dead gum tree, cut up into sections and painted white. The tree carcass makes an effect particularly in juxtaposition with H. J. Johnstone's Evening Shadows, Backwater of the Murray, South Australia (1880), one of the most popular pictures in the gallery's collection, of which countless copies were made in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Jones has borrowed a large number of these copies for an installation in the second part of the exhibition, in the Elder Wing.

Johnstone's picture is far from great art. It is based on a photograph, which explains its general flatness and kitsch effects of light, although these features were what appealed to popular taste. Jones wants to link it to an Aboriginal demonstration that took place on the spot in 1939, and the connection is not entirely unjustified, given the importance of Aboriginal figures in the original composition, but his own charcoal drawing re-imagining part of the negative of the original photograph is more poignant than anything else in its quiet, non-tendentious evocation of loss and loneliness.

In the same room, two photographs by Rosemary Laing also evoke the bush and our presence in it. One of them in particular, suggesting the wooden frame of a suburban kit home sinking into a moody landscape of hills and ancient gums, makes effective use of a dry humour, that quality so often promised and hardly ever actually present in contemporary art - it is, for example, completely absent in Rob McLeish's sculptures, despite the assertions of the room brochure.

A set of works by Ricky Swallow shows him again - as at the end of his National Gallery of Victoria retrospective in 2009-10 - trying to reinvent himself as something other than a wood carver, and with the same mixed success; one vertical bronze stands out from all the others. Nearby Michelle Ussher's paintings and ceramics are too fey to sustain one's attention for much longer than it takes to walk through the display. Pat Brassington's photomontages, looking back to dada and surrealist models, create disconcerting effects by mismatching figures with an interior environment, either in scale, in orientation or in the plausibility of the motifs.

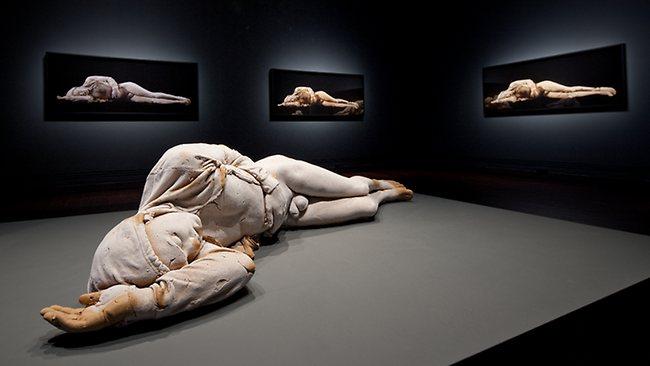

The single most memorable display is Tim Silver's life-size figure, cast from his own body and executed in wood putty, which will dry out, shrink and crack over the life of the exhibition. The body lies pitifully on a low plinth, half naked and as though dead, an image firmly in the northern realist tradition of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. For these Netherlandish and German artists, far more imbued with Christianity than with the example of classical art, the body is polluted with sin, morally corrupted and doomed to physical decay. It is a disturbingly anti-humanist vision which, if not redeemed by Christian promises of another life, ends in sterile nihilism.

We pass through a room of traditional Tiwi art that is quite attractive in itself, but appears to be there because curators believe they need to include some traditional Aboriginal work in any contemporary show, however incongruous it may appear in this setting. After this there is a large installation of a figure in water by Shaun Gladwell - surely an overrated artist - trying to do the sort of thing Bill Viola does much better.

Upstairs in the Elder Wing, the most remarkable thing is the installation of copies of Johnstone's Evening Shadows: what is interesting is that not one of these copies is identical; there are differences of proportion, drawing and even of colour - presumably some, at least, were made from colour reproductions, which may themselves have distorted the picture's colour scheme. A couple of larger and more elaborate copies, handsomely framed, were presumably made from the painting itself.

One of Laing's photographs stands out again in this section, a large landscape titled After Heysen. The room brochure obtusely declares that it "highlights the historically and culturally loaded depiction of landscape", but this is just the artspeak thought simulator generating verbiage while the brain is disconnected. What Laing's picture really shows is how cultural forms help us give imaginative shape to a world of experience that could otherwise be shapeless and unintelligible.

Most of the rest of the material is forgettable, though there is a bust by Silver in a glass case. What one cannot forget, however, is the insistent buzzing soundtrack by Philip Samartzis, which the brochure assures us is meant to "enhance our perceptual awareness of place" and - humour in this kind of writing is always unintentional - to "disrupt the natural ambience of the gallery".

I think we can agree that Samartzis has achieved this purpose, and indeed has delighted us long enough. Perhaps they could switch him off now.

Parallel Collisions: 12th Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, to April 29