Donald Friend: beyond the sins of the artist lies undeniable greatness

Can we look beyond the repugant acts of the artist and see Donald Friend’s art for its brilliance alone?

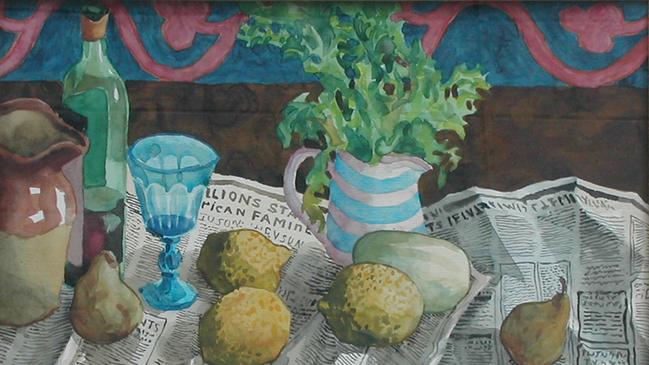

For much of the second half of the 20th century, Donald Friend (1915-89) was considered an important and distinguished modern Australian artist – not perhaps quite on the same level as his friend Russell Drysdale but in some ways, especially in the fertility of his graphic invention and his brilliance as a writer, equally prominent and interesting. His work was widely appreciated, held in all major collections, and shown in many exhibitions; the Art Gallery of NSW devoted a retrospective to him in 1990, the year following his death.

The quality of his writing was revealed more broadly to the world with the posthumous publication of his diaries by the National Library of Australia. Four volumes appeared, in 2001, 2003, 2005 and 2006. They were a literary phenomenon: eloquent, incisive, witty and filled with the vivid and completely uncensored narration of a remarkable life. They were immediately compared, not to other Australian diaries and memoirs, but the greatest examples of the genre in modern European literature, like those of Samuel Pepys in Restoration England, a favourite period of Friend’s.

Friend was too frank for his own good, and several passages in the final volume about sex with underage houseboys in Bali were met with the horror that the subject had come to inspire in those years in Australia and the Anglo-Saxon world. Friend was suddenly a monster and there was pressure to cancel him. Gallery directors demonstrated their customary courage and independence by hastily taking down his pictures from their walls; the diaries too disappeared from the shelves of bookshops, especially in art galleries.

Certainly the acts he referred to were wrong and repugnant, but was this the right reaction? Artists and intellectuals have through the ages done horrible things: Cellini, Caravaggio and Borromini all committed murder; Bernini had his mistress beaten up; others have raped models of both sexes; Ezra Pound and Louis-Ferdinand Céline were Fascist and Nazi collaborators respectively; countless left-wing authors have defended murderous Communist régimes. Yet it would be ludicrous to cancel these individuals.

Such was the terror of being associated with Friend’s name that Ian Britain had great difficulty in securing a publisher willing to produce the present biography, and even when it was finally accepted by one undaunted by the fear of opprobrium, it was hard to find bookshops willing to put this volume in their window or on their tables. These are regularly stacked with hundreds of predictably anodyne volumes in various genres, all described as exciting, provocative, challenging boundaries and so on. But alas, the boundaries that cannot be challenged are all too evident when something like this comes along. Some bookshops in Sydney have the courage to stock this book; if your local bookshop doesn’t, it can readily be ordered online.

Britain has not attempted to write a comprehensive life of Friend, which would be both a daunting task in view of the brilliance of the diaries themselves and for the same reason a partly redundant one. Instead he has focused on the artist’s early years, before he began to keep a regular diary. This is a period of which we otherwise know very little, and that is only alluded to sporadically and not always consistently or accurately in the diaries, letters and interviews from decades later.

An artist or a writer’s formative years are particularly important because they represent the period when a young mind and sensibility are taking shape; in retrospect we can imagine this as a simple process of maturation or germination, as though of a seed that is planted at the outset. But when we look more closely we can see how inner necessity and drive are shaped and modified by environment, opportunity and the reception of early efforts at expression.

In the case of a subject such as Friend, the study of his early years turns out to offer a cornucopia of insights about other periods and environments, from the early colonial history of Australia to the culture of Sydney modernism and the bohemian milieux of London in the years before the World War II. These insights are a credit to Britain’s meticulously accurate research, which incidentally corrects many errors and misdatings in the artist’s life and in the earlier history of his family.

This research includes considerable reading on even minor figures who cross his subject’s path – especially when these individuals have left memoirs or published correspondence – and the story benefits immeasurably from bringing countless minor figures to three-dimensional life. It gives some idea of the author’s attention to detail that even the identity of individuals mentioned in passing in gossipy letters on the voyage home from Africa in 1940 are tentatively identified from a study of the contemporary shipping lists.

But if virtually every fact asserted or date cited is backed up by sources quoted in endnotes to each chapter, Britain’s text is free of the vices of most academic biographies. As the former editor of the literary review Meanjin, he knows how to write, and his prose flows smoothly and clearly, free of jargon, ideology and editorialising. It is the writing of someone who is warmly interested in his subject, critically attentive to accuracy, and intent on conveying what he has discovered to his reader in the clearest and most effective manner. The result is a book that engages us at once and which is very hard to put down once we start reading it.

The first section elucidates the origins of Friend’s family in Australia, which go back to the very beginning of settlement at the end of the 18th century. We start with the story of a young man who is deported for breaking into a haberdasher’s shop window with a diamond cutter and stealing lace but who, like so many, remakes himself in Australia first as a baker, then a storekeeper. His son turns the bakery into a flour mill, acquires grazing leases, becomes a banker and a member of NSW parliament. Generations follow in a fascinating picture of the opportunities available to the enterprising in a new land.

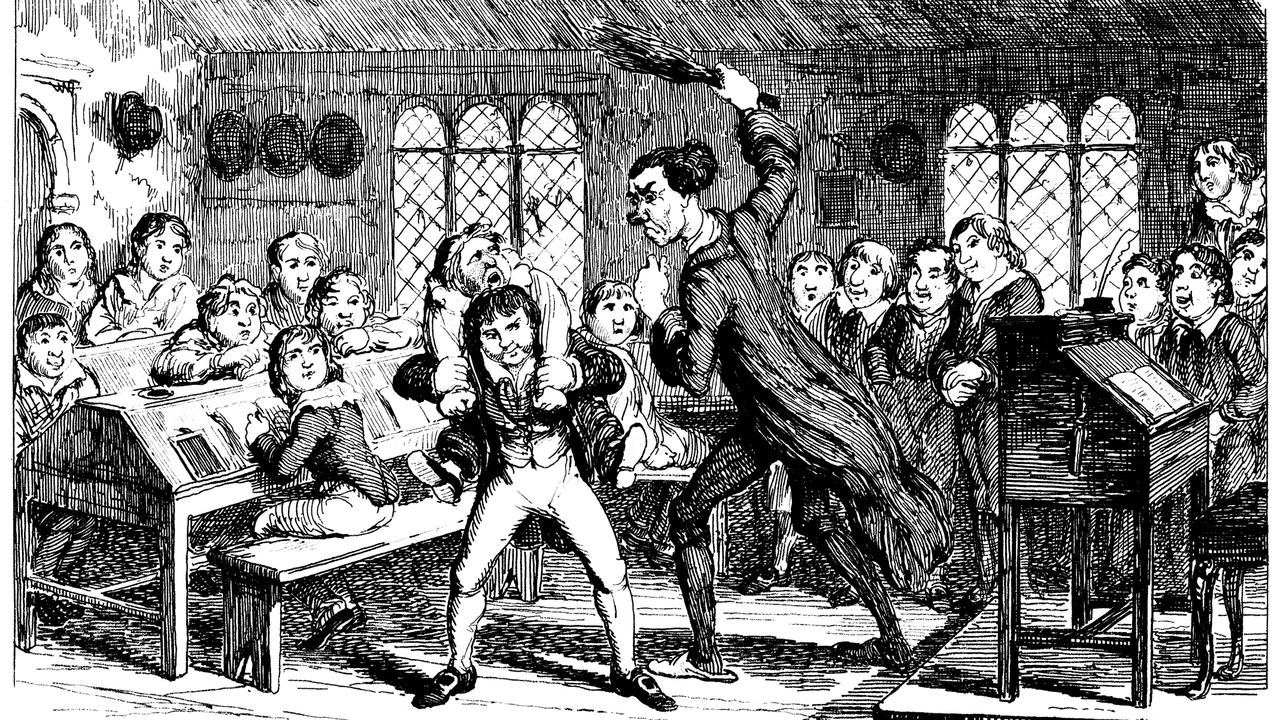

Donald himself was born just a little over a century later, by now to a wealthy grazier father and a mother who was herself from a well-to-do and cultivated family. His parents’ marriage broke down when he was a little boy and he saw very little of his father. For a time his mother lived in the city with the four children; Donald attended several schools, including Tudor House in Bowral, Cranbrook as a boarder and then Sydney Grammar as a day boy. This was partly because the Depression was gradually strangling even his family’s finances, and when things got particularly hard, he left Grammar in May 1931 at the age of 16 and moved back to one of the family properties, where he lived with his mother and siblings; his father stayed on the other main property. It was on the whole a privileged background, despite the relatively straitened circumstances the family endured for a few years, but even though Donald was a precociously well-read and articulate young aesthete whom his father suspected of being an effete “sissy”, this early formation somehow produced instead a tough, hardy and adaptable young man. At the core of this perhaps was an implicit sense of patrician freedom which exempted him from petit-bourgeois anxieties about the markers of rank and respectability; and a physical self-confidence which allowed him to take risks and suffer discomfort without losing his inner equilibrium.

One expression of this freedom and self-confidence is in relation to his homosexuality. There were early crushes and heartbreaks, but there was never any of the closeted self-hatred, denial, or anxiety about gender and identity that we hear of today when social attitudes and laws are so different. Donald seems from the beginning to have had a confident sense of himself as a man and to have formed a succession of relationships with other men without guilt, complexes or even furtiveness.

Even earlier, he demonstrated his boldness and physical endurance when he left the family property in early 1933 at the age of 18 to make his way up to Queensland as a hobo. It was a harsh and dangerous life on the road with practically no money, but he was drawn to the adventure and the challenge. And despite, or perhaps because of, his class he was at ease with people of entirely different backgrounds, such as the fellow-hobos he befriended. He was similarly, throughout his life, utterly free of the sense of racial barriers, and in Cairns he was virtually adopted by the Islander family of Charlie Sailor whom he visited again on later occasions.

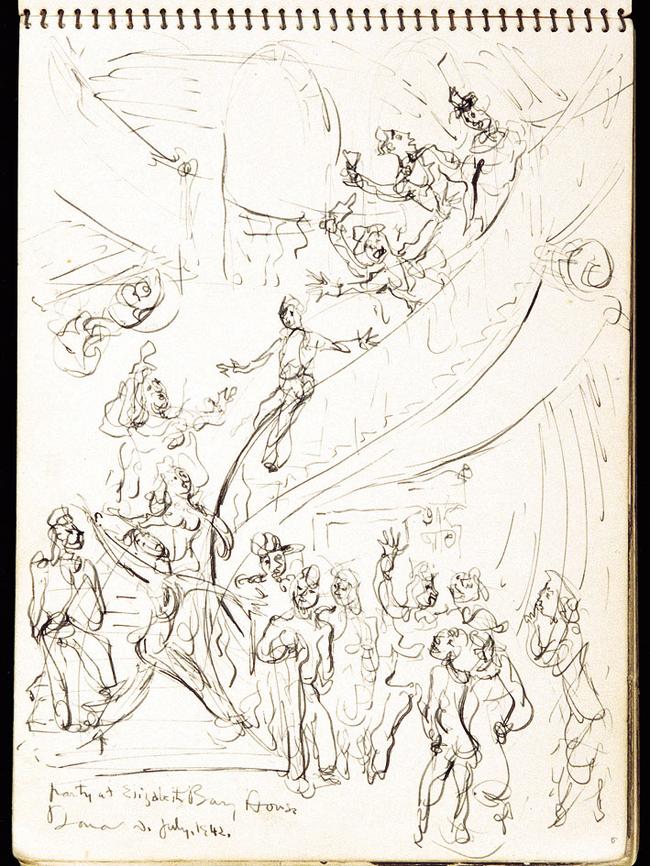

After these adventures, the book relates Donald’s life in Sydney as an art student (1934-36) at Dattilo Rubbo’s school, while living in Kings Cross, and then, from October 1936, his further studies at the Westminster School in London, where he has a relationship with a young Nigerian called Ladipo. In both Sydney and London his life intersects with a picturesque cast of artists, intellectuals and eccentrics of every kind. Thanks to the voyeuristic orgies organised by his art dealer, he seems to have fathered a daughter with one of the dealer’s mistresses, although there is some uncertainty about the date of conception.

Having finished his studies in London and growing weary of so many of his colourful but often “bogus” acquaintances, he set off on another adventure in September 1938, sailing to Nigeria, where he immersed himself far more deeply in the culture of the local people and famously became an adviser to a local king, the Ogoga of Ikerre. And this was not, as some might suspect, a pretext for finding more black lovers, for homosexuality was rare in Nigeria and he endured 16 long months of chastity at the age of 23 and 24.

Back in Australia in 1940, Friend began to achieve a measure of recognition before joining the army in 1942, and simultaneously starting the diary that he would keep for the rest of his life. This is, as already mentioned, an absorbing biography, both because of its subject’s exceptionally adventurous and unconventional early life and because of the invaluable work that Britain has put into reconstituting the colour and texture of these early years. The sequel can be read in the diaries themselves, or in the excellent one-volume abridgement edited by the same author. At some point early in his life, Friend spoke of putting his genius into his art and his talent into his writing, but we may be tempted to feel that – for all his remarkable virtuosity as a draughtsman – it was really the other way around.

Donald Friend

Ian Britain

The Making of Donald Friend: Life and art

Yarra & Hunter Arts Press, 2023

Donald Friend, ed. Ian Britain

The Donald Friend Diaries: Chronicles & Confessions of an Australian Artist

Text Publishing, 2010

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout