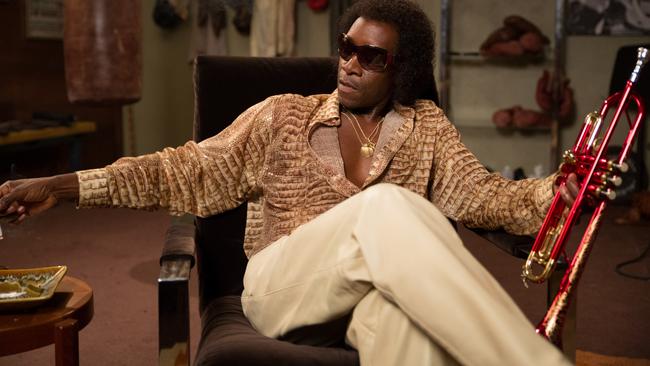

Don Cheadle’s Miles Ahead: sketches of a musician

Miles Ahead is not a cradle-to-the-grave biopic of Miles Davis but an impressionistic blending of timelines.

Don Cheadle has bent the rules in his impressive and innovative film about music-changing jazz musician Miles Davis. He’s done so in an I’m-in-charge manner he hopes the man himself would relish. Miles Ahead (the title of a 1957 Davis album) is not a cradle-to-the-grave biopic but an impressionistic blending of timelines, as well as fact and fiction, that tries to tap the soul of a brilliant, radical and at times bothered artist. “I was more interested in making a movie in the way I think Miles Davis would approach the medium,’’ Cheadle said in a recent interview, “and create a film that he would want to star in.’’

Davis died in 1991 aged 65. In 2006 he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and it was around this time that Cheadle became friendly with Davis’s family. It’s taken him a decade to bring the film to life. He’s the star, it’s his directorial debut, he’s a co-producer and he co-wrote the script with Steven Baigelman. A few Oscar nomination possibilities there but my money is on the acting one. Cheadle’s limping, rasping, chain-smoking, cocaine-snorting, gun-wielding, Jaguar-owning, sunglasses-protected Davis is a mesmerising motherf..ker, to borrow one of his favourite words in the film. He learned the trumpet for the role — and while I’m no expert, it looks and sounds right.

Cheadle is a fine actor, probably best known for his stints in blockbusters such as Ocean’s 11 and its sequels, and the Iron Man and Avengers superhero movies. I still remember him most, though, from two 2004 films: Hotel Rwanda, for which he received an Academy Award nomination, and Paul Haggis’s Oscar-winner Crash. As director and star he puts Davis in our face, close-up and smoking, from the opening moment. “If you are going to tell a story, man,’’ he nicotine-gravels at an interviewer, “come with some attitude.” It’s an edict for what is to follow.

Miles Ahead unfolds over just two days in Davis’s life, in 1979 when he, having abandoned his career five years earlier, is living in solitude in New York, smoking and drinking and snorting and complaining. “I didn’t have anything to say,’’ he says when asked why he stopped writing music. He also refuses to call his music jazz, preferring “social music”. But it seems he has made a new session tape, one his studio is desperate to have, even if that means bidding semi-gangsters to do the fetching.

The rumours of a Davis comeback bring Rolling Stone journalist Dave Braden (a fictional character) to the legend’s door. This reporter is played with humour, edginess and a bad haircut by Ewan McGregor: hiring him helped Cheadle finally finance the film. “Jazz’s Howard Hughes, reviled and revered,’’ Dave tells his tape recorder. Davis punches him in the nose, but after that they more or less join forces to protect the star from the studio.

There’s drug-taking, fistfights, car chases and shots fired. Cheadle and McGregor are closer in mind than their characters would think. When, after a big night, Scottish Dave says he can’t remember what happened because “I was off my tits”, Davis’s perplexed reaction is funny. He almost smiles.

There are some sustained high-note scenes that have the late 1970s stamped all over them. Davis, gun in hand, walking into the studio offices to deal with the money-hungry executives; Dave and Davis scoring cocaine from a wealthy university student.

It’s also rare to see a new film in which fixed phones have such a prominent role. When a radio station plays an old Davis song and the announcer says it’s one for the time capsule, the artist picks up a phone, fingers the yellow pages and makes a corrective call.

This dry yet fast two-day story is intertwined with moments from Davis’s life in the late 50s, when he met and later married dancer Frances Taylor (a wonderful Emayatzy Corinealdi). These are not presented as flashbacks, however, but as seamless transitions so that the present becomes the past and vice-versa, an absorbing technique that ends up presenting time as one moment when, late in the film, Davis is alongside a rising young musician who could be an earlier version of himself.

Davis comes across as a chauvinist and a man with anger issues. “He never hid the good, the bad or the ugly of his life,’’ Cheadle has said. Even so, I’ve seen comments by Davis fans that cut both ways: some think he comes across as badder than he was, some think not bad enough. There are also criticisms that the film covers events that did not occur. As someone who is not in one of these camps — I own a few Davis CDs but I know not much about him — I watched it unhindered by such presumptions and found it an imaginative and absorbing piece of filmmaking. It also made me want to buy the Davis album that is most used in the soundtrack: Sketches of Spain.

Miles Ahead (M)

4 stars

Limited release