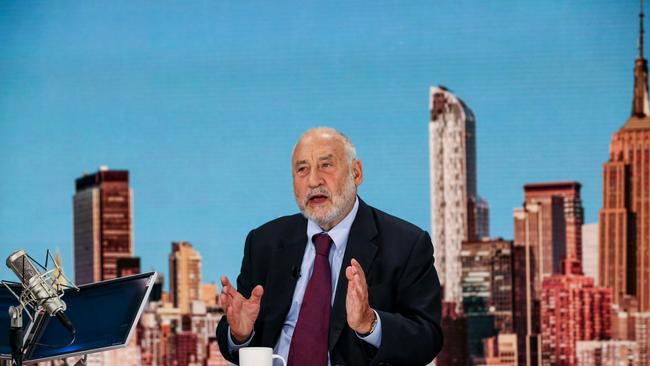

Distinguished economic Joseph Stiglitz offers his capital ideas

Joseph E. Stiglitz’s Road To Freedom writes passionately about economic fairness but what does this mean in practice?

Joseph Stiglitz, now 81, has had a distinguished career as an economist. He is still teaching at Columbia University. He is a Nobel laureate in economics, must have enjoyed watching The West Wing on television (1999-2006) and may well have wished it was him rather than Josiah Bartlet (played by Martin Sheen) in the White House during those years.

He was chairman of president Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers and chief economist at the World Bank between 1993 and 2000 – which includes the period in which the Glass-Steagall Act on banking regulation was repealed. That opened the way to unbridled abuse of derivatives and the disaster of the global financial crisis (2008-09). He did not get on well with Lawrence Summers, then secretary of the Treasury and an ardent advocate of deregulation.

Throughout his career he has been an economic moderate and he is now a trenchant critic of “free market” economics. This new book is an impassioned critique of Friedrich Hayek’s classic liberal manifesto, The Road to Serfdom (1944), which claimed that Keynesian intervention in the market was setting the Western capitalist states on the road to totalitarian control and bureaucratic stagnation.

Stiglitz, long known for his espousal of a land tax in the tradition of Henry George, here uses John Rawls rather than George as his point of reference. Published in 1971, Rawls’s A Theory of Justice famously argued that justice meant fairness and that fairness ought be calculated by two criteria: how would you order society if you did so from scratch, but behind a veil of ignorance regarding what would become of you or anyone else; and disproportionate effort ought be made to weight redistributive measures in favour of the worst off in society.

Unfortunately, in this book he doesn’t introduce his reader to Rawls’s actual argument, only to his conclusions. Moreover, he fails altogether to mention the famous response to Rawls by Robert Nozick, published in 1974, Anarchy, State and Utopia, which made a very different and rather brilliant argument that the best state was a minimal one. Stiglitz appears to assume that a critique of the apparent consequences of the “neo-liberalism” of Hayek (and Milton Friedman) subsumes the arguments of Nozick.

Read alongside Jonathan Aldred’s Licence to be Bad: How Economics Corrupted Us (2019) and Martin Wolf’s The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism ((2023), The Road to Freedom can be taken as a call for political and economic reassessment and rebalancing, starting in the US, which is Stiglitz’s mother country. It’s well worth reading in that context.

Where it leaves this reader, at least, dissatisfied is in its failure to address two fundamental empirical challenges: first, given the very substantial redistribution of wealth he calls for, Stiglitz fails to offer any data at all on how all this could be funded; and second, he makes no attempt to show how such an agenda could be turned into a viable political platform in the US as it is, which is very far from being behind Rawls’s famous veil. Wolf does better. He opens his 2023 book with the remark that his parents, both Jewish, were refugees from Hitler’s Europe whose wider families were exterminated in the Holocaust because they failed to heed the warning signs in the 1930s that massacre was coming. He was born in London in 1946 and grew up in the shadow of the catastrophes of the first half of the 20th century. He argues that we are now in danger of similar catastrophes and that a revitalised, principled democratic capitalism is our best hope to avoid them.

Like Stiglitz, Wolf looks back to earlier theorists as a point of reference. He draws the attention of his readers to Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, which was published, as he points out, in the same year as Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Human beings, he cites Polanyi as having observed, “would not long tolerate living under a truly free market system”. He adds: “Experience of the past four decades has vindicated this point of view.”

But this leaves very wide scope for economic and political platforms that actually do not work very well.

Wolf acknowledges this rather more explicitly than does Stiglitz. How many times do we hear apparently intelligent people declaring that the answer is to put an end to capitalism? William Cohan’s Why Wall Street Matters (2017) is a concise and sensible antidote to such thoughtless rhetoric.

But considerable danger lurks in vague ideas about Edenic pasts or easily accessible, if coercive, utopias. When assessing good and bad, property and taxation, state and productivity, our passions and intuitions need educating. As James C. Scott showed in Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States (2017), the “state” arises late in human history (about 5000 years ago) and is coercive and fragile from the outset, not Rawlsian or Nozickian.

Stiglitz has his heart in the right (Rawlsian) place. But he avoids the hard work of trying to show us how, from our current difficulties, we can get to such a redistributive place.

Paul Monk is the author of a dozen books, including The West in a Nutshell (2009), The Secret Gospel According to Mark (2017) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout