Desire Lines at Melbourne Town Hall, a rewarding exhibition

Sydney’s CBD is full of bland glass and concrete towers. Melbourne, in contrast, seems to have preserved, with its Victorian urban fabric, a certain Dickensian squalor.

Melbourne is perhaps more truly a city for the “flaneur” than Sydney, not only because of its generally older urban fabric – in spite of its later foundation – with its arcades and characteristic lanes, but because altogether and even in its population it feels somehow closer to a city of the 19th century like London or Paris, where the very idea of the half-aimless, half-curious urban stroller originated.

The verb flaner should by rights have some distant parentage with the Greek planao, used among other things of the wanderings of Odysseus, but in fact turns out to come from Old Norse. Its modern sense, though, which we associate with Baudelaire and later the essays of Walter Benjamin, is distinctly Parisian. Victor Hugo, alluding to the Latin saying that we translate as “to err is human, to forgive divine”, wrote in Les Miserables (1862) “Errer est humain. Flaner est parisien”.

Flaner means primarily to wander without a fixed purpose, but its connotations range from mere dawdling or taking one’s time to finding an idle yet curious interest in the random things we encounter; Flaubert uses in Madame Bovary (1857) of wandering among one’s memories. Used today of looking through a bookshop, for example, it means to browse.

The city of Sydney does not lend itself as well to such wandering; the central business district is all rebuilt in bland concrete and glass towers that have neither past nor future, since they are all destined to be demolished and replaced every generation or so: this is an environment with little character because it has no history and no memories. And you can’t browse in the confected environments of shops and cafes artificially fitted out inside concrete shopping centres.

Nor is the human environment very interesting when the streets are filled with presentably dressed, relatively healthy, well-adapted and efficient office workers, the kind who have all been approved by the HR department as good employees with the right attitude. You have to go to Kings Cross for a more dramatic mixture of rich and poor, beautiful and ugly, intellectual and illiterate, entrepreneur and unemployable. The other so-called villages of Sydney can be picturesque too, although most have now been transformed by money, fashion and “lifestyle” consumerism.

Melbourne, in contrast, seems to have preserved, with its Victorian urban fabric, a certain Dickensian squalor even in the inner city, although in fairness this may be because I tend to spend much of my time in the area between the NGV, Federation Square and up to the State Library or even the University. No doubt it’s also because Flinders St Station is in the middle of this area; but it always seems to be filled, day and night, with people who are the opposite of those you see in inner Sydney.

These people remind you of the levels both of economic want and of cultural impoverishment and desolation in which much of the population exists. There is a stark difference between the mental lives and general awareness of the crowds in Swanston St and of those who frequent the NGV or the Arts Centre nearby; that difference is ultimately a matter of wealth, but its immediate cause is the level and effectiveness of the education that each group has received.

On the day our story begins, as a 19th-century narrator might have written, some of the more dangerous members of Melbourne’s underclass held a neo-nazi rally on the steps of Parliament House; I didn’t witness this, but instead encountered a much tamer and rather bedraggled demonstration passing through Swanston St, composed of superannuated leftists protesting against the AUKUS alliance, joined by a handful of Filipino communists and sundry others.

Beyond this little procession, I discovered the very small City Gallery, on the ground floor of the imposing Melbourne Town Hall, and an exhibition put together by an Irish artist, Sean Lynch, browsing through the Melbourne city collection in the spirit of a flaneur exploring the city itself.

The gallery is tiny, a single square room, and the exhibition is a modest one, arranged in a necessarily compact manner; but Lynch succeeds in drawing together a number of things that, perhaps unexpectedly, provoke interesting reflections, especially given the proximity of the real city outside.

As we approach the gallery, for example, we pass the enormous building sites of the new Melbourne Metro system which, like the Sydney Metro site which has occupied much of Martin Place for the last couple of years, is intended to modernise the mass transit networks of our biggest cities.

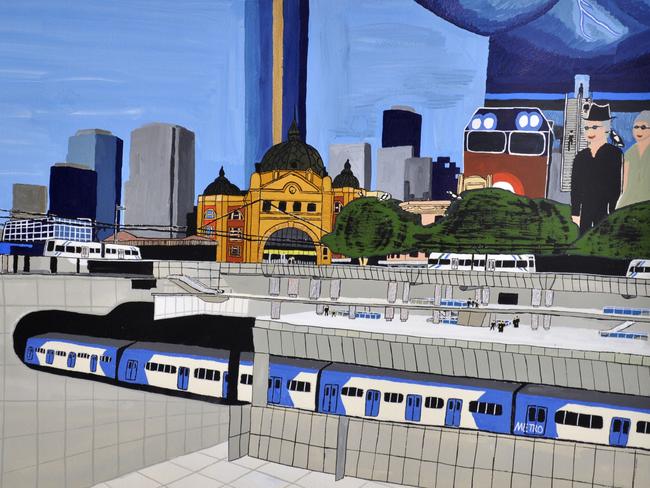

In the exhibition itself are a couple of watercolours that evoke the new trains and tunnels, more of an innovation for Melbourne since, unlike Sydney, it has never had an underground. Thus one of the watercolours dramatically evokes a massive train driving through a tunnel beneath Flinders St Station, and the figures in the composition are dressed in the clothes of around 1900, recalling the time when underground trains really were a new idea (the London Underground began in 1863 and the Paris Metro in 1900) and when some at first questioned whether people would be willing to travel through subterranean tunnels.

Several of the items are whimsical, like a set of brass letters that composed the words “City of Melbourne” displayed in a heap, while the wall behind them is inscribed with rearrangements of these letters into partial anagrams, like those word-puzzles in the daily papers. Some of these combinations, lying hidden in the city’s name, are unexpected, from “bucolic” to “country mice”.

There are also a couple of old black and white photographs of pigeons densely nesting on the acanthus leaf ornamentation, today bristling with deterrent spikes, of the Town Hall’s Corinthian columns – the occasion, in the accompanying catalogue booklet, for a digression on the legendary origin of the Corinthian order.

More substantial is a set of photographs, or more exactly photomontages from an exhibition mounted in 1986 by Ken Scarlett, an authority on Australian sculpture, and making the case for the installation of more public sculpture throughout the open spaces of the city. These images were made by separately photographing the proposed locations and the sculptural works – or their maquettes – and then combining the negatives in the process of printing and enlarging; the sort of montage that is now done digitally with the aid of tools like Photoshop was then carried out manually and required a great deal of skill and especially darkroom expertise.

The question these images inevitably raise, however, is why anyone would want to install such sculptures in a city square. The objects themselves look somewhat dated today but were never beautiful or inspiring pieces of sculpture; they are, like most art produced at any time, little more than variations on once fashionable themes and forms.

But even if they were things of enduring and perennial beauty, the question remains why one would put them in a public square. A public sculpture is not just an ornamental object, it has to have civic meaning as a monument or memorial; the most successful public sculptures are generally statues of monarchs, governors or other significant individuals such as scholars or philanthropists, or else memorials to battles and the dead in war.

In Australia’s case, many of our best monuments are to explorers like Captain Cook (by Thomas Woolner, 1879) in Sydney’s Hyde Park or Matthew Flinders, represented in both Sydney and Melbourne, because the mapping of the continent, both maritime and inland, was so crucial a part of the story of settlement.

One of the most important such memorials in Australia is Charles Summer’s statue of Burke and Wills (1865), which is also the first bronze statue cast in Australia. Their expedition, which started off with such hopes and fanfare – celebrated in several contemporary paintings – ended in disaster, but became all the more legendary as an example of the kind of tragic failure that has a special place in the Australian psyche.

The statue itself, in which the figure of Wills is inspired by Michelangelo’s figure of Duke Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici as the embodiment of active life in the Sagrestia Nuova in Florence, actually appears in this exhibition as part of an architectural maquette, although the monument itself was removed during the building of the Metro and will be replaced when the works are completed.

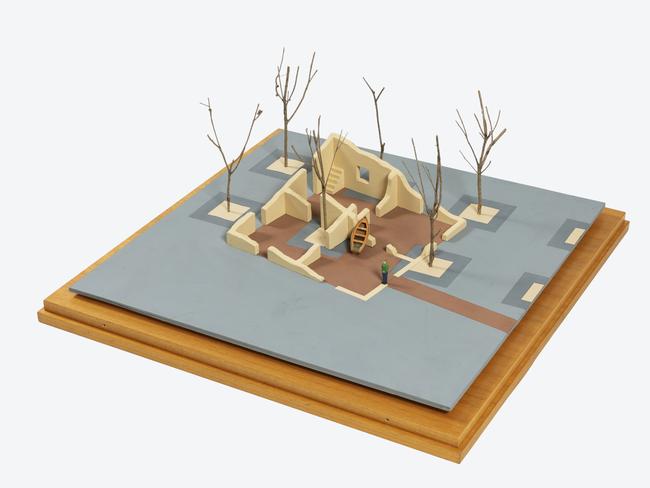

Perhaps the most interesting item in the exhibition, however, is another maquette, of an installation built on the banks of the Yarra River by the late Hossein Valamanesh, who sadly died last year. This was not a monument or a memorial, and had no ostensible civic intention, but was rather a hybrid of architecture and sculpture that invited contemplation and the imaginative participation of the viewer.

The maquette was made in 1993, and the work itself erected in 1996, if that is the right word for a structure that simulates a ruined house. The remains of broken walls rise among the trees planted on the banks; a bronze figure stands near the ruins of what we assume to be his home; in the middle of the house, a small boat, a dinghy made of bronze, rests on the crumbling masonry as though it had been deposited there by the same flood waters that had destroyed the house.

The boat reminds us of Ortega y Gasset, who compared our existential position in the modern world to that of a shipwrecked man; and ruins are a theme with a long history in art and literature, especially in the romantic period. The ruin of a house is particularly poignant, and is a motif we encounter in Drysdale’s paintings of outback houses gutted by fire.

Sadly, this artificial ruin was, for whatever reason, not constructed soundly enough to sustain the many stresses of public art (there is a reason why monuments are made of bronze and raised on pedestals).

The walls were of sandstone veneer and soon began to break down; I was told that taxi-drivers found the interior corners discreet places to urinate; one of the bronze oars was taken from the boat and someone cut off the standing bronze figure with an angle grinder and stole it, possibly for the bronze.

Faced with the increasingly dilapidated state of the work, the City Council determined to demolish it after little more than ten years, in 2007. The boat, with its remaining oar, is in storage somewhere, and all that remains at the site are the vestiges of an old wharf that was incorporated into the installation, and a red stone “fault-line” in the pavement.

And so the maquette in the exhibition has a particular value, as the melancholy relic of a gentle and poetic meditation that seems so alien to the brash vulgarity of Southbank today, with its monstrous casino and loud overpriced restaurants.

Desire Lines, Melbourne Town Hall, until July 26.