David Stratton’s cinematic life documentary a poignant memoir

Film helped critic David Stratton understand his adopted home of Australia.

Let’s start with this: David Stratton isn’t always right about a film. “I have known him to change his mind,’’ Russell Crowe notes in one of the dozens of star-studded interviews that add to the celebrity yet also the intimacy of this fascinating documentary on 77-year-old Stratton and the movies that made him.

The critic does confess to changing his mind — though only once, it should be noted — during an endearing discussion of the near-iconic 1997 comedy The Castle. He didn’t like it much the first time around. He says he thought the characters were caricatures, a judgment that prompts a cracking response from lead actor Michael Caton: “They were my own Ugg boots!” Twenty years on, Stratton admits he better understands the film and values it more.

I started with that moment of Strattonian self-deprecation as an alternative to the sort of disclosure that might be expected. Yes, Stratton is a colleague — he has written for this newspaper for more than 20 years — and I’m reviewing a film in which he stars. Well, I can only do what I always do and say what I think. This is a brilliant, profound, at times moving documentary that is a must-see for anyone interested in how art can change people, countries and even history. If you have followed Stratton as a critic, you will learn a lot over an hour and 40 minutes: about the movies and the man himself. Would his former television co-host Margaret Pomeranz agree? She pops up here, with charm.

David Stratton: A Cinematic Life is written and directed by Sally Aitken, a Kiwi who has made acclaimed local TV series such as The Great Australian Race Riot and Streets of Your Town. The executive producer is Jen Peedom, who in 2015 wrote and directed the fine feature film Sherpa. The cast is David Stratton and a roll call of his famous friends. If they were commanding their usual wages the budget would have nudged $100 million. It’s a mark of the respect in which Stratton is held. We first hear from Nicole Kidman, who is followed by Jack Thompson, Jacki Weaver, Bryan Brown, Judy Davis, Sam Neill, Sigrid Thornton, Rachel Griffiths, Geoffrey Rush, Hugo Weaving, Crowe, Gillian Armstrong, George Miller, Fred Schepisi, Jocelyn Moorhouse, Bruce Beresford, David Michod, Warwick Thornton and many more.

Stratton does a lot of the interviews himself. He’s a natural in front of the camera. It’s clear the actors and directors feel comfortable with him. There’s much humour. There are also unguarded moments, when the conversation is banter between friends rather than an interview. Neill, remembering Armstrong’s 1979 adaptation of My Brilliant Career, says co-star Davis made it clear she thought he was a lightweight. He adds with a laugh that her opinion hasn’t changed. Davis’s own interview is full-on, and Stratton has admitted that some of it was too ripe to go to air.

For all the joys of such A-list chatter, this is much more than a film about a critic and the filmmakers he knows. It’s a memoir where everything connects. The actors and directors are most interesting when they discuss their inspirations — Armstrong on Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock, for example — and the artistic and censorship challenges of making movies in this country, particularly before the 1970s.

But the centre of this story is Stratton, who came here in 1963 as a “10-pound Pom”. He was supposed to stay for two years and then return to the five-generation-old family grocery business. He stayed put and his father was furious, as Stratton’s brother Roger plainly puts it: “We get on all right but we are not close because we have nothing in common.’’ When Stratton remembers this he is close to tears, blaming not his father but himself. “I was probably a nasty child. Yes, I was, I think.” This is a Stratton we did not see on TV and the result is poignant.

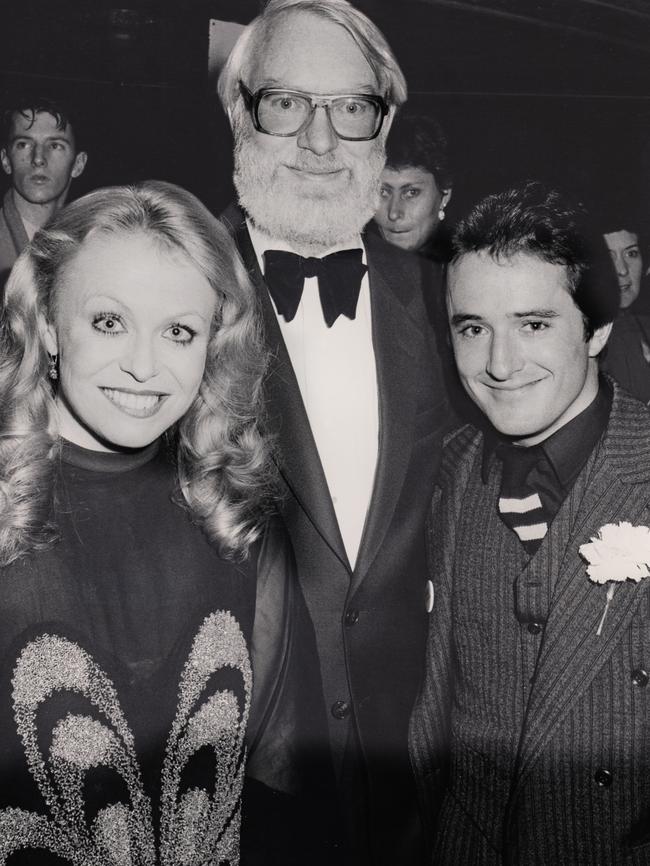

He was obsessed with film from childhood. It was his “religion”. As an adult he ran the Sydney Film Festival for 20 years (after starting as an usher), then wrote for Variety, then had a long TV career on SBS and the ABC. We see old clips of him covered in 70s hair and a Lenin beard.

He has seen more than 25,000 films and keeps fastidious records of them, including his reviews, in ring binders. Asked to find his first “review”, of the Chips Rafferty wartime droving movie The Overlanders, he unhesitatingly pulls down the 1946 folder and unbinds the 70-year-old piece of paper covered in his seven-year-old handwriting. He knows such records can be kept online but “I like my own system”.

It’s tantalising to realise this documentary is only about Australian filmmaking. Stratton could make another one about his engagement with directors and actors from the US, Europe and elsewhere — and I’d jump in the queue to see it. He used Australian films to come to grips with his new home. There’s a superb discussion of the 1971 classic Wake in Fright (directed by another outsider, Canadian Ted Kotcheff, who is hilarious about Rafferty). He also used them to understand his fragile English childhood.

He knew what it felt like to be the city schoolteacher posted to the outback in Kotch-eff’s film, the boy war-torn from his father in Carl Schultz’s Careful He Might Hear You and even the titular character in PJ Hogan’s Muriel’s Wedding. “Like Muriel Heslop I know what it’s like to be the black sheep of the family.’’

There are clever cuts to movie scenes as Stratton and others reflect on his life, such as to Anthony LaPaglia in Ray Lawrence’s Lantana booming to one son, “Your brother’s an idiot.”

“In some sort of weird way,’’ says Sigrid Thornton, “David is representative of what film can do for a population because he’s come to understand his adopted culture through film. It’s a beautiful thing.’’

One of the challenges was narrowing down the number of films included. “I can’t imagine a life without film,’’ Stratton says at the start. “I try to see a film every day. At least one. I am going to share with you some of my favourites.’’

He covers about 100, with engaging discussions of Picnic at Hanging Rock, Strictly Ballroom, Head On, Mad Max, Evil Angels, Samson and Delilah and many more. The sequence on Scott Hicks’s Shine, with Rush, is a highlight. More films will be included in a three-part version of this documentary that will run on the ABC in late May. There’s a final interview with the director to whom the film is dedicated: Paul Cox, who died last June. Stratton knew him well and loved his art.

Stratton includes some films he hates, such as the dystopian horror thriller Turkey Shoot, as part of a broader discussion of the 80s “ozploitation’’ wave. Nor has he changed his mind about the violent Romper Stomper, starring Crowe as a Melbourne neo-Nazi. He refused to rate the film on its 1992 release. In turn, director Geoffrey Wright says the “pompous windbag” did him a favour by increasing publicity.

Stratton covers so much here it seems unfair to complain about omissions. But I do think his weekly work for this newspaper should be mentioned. I’d also like the authors of books that become films to be acknowledged. We hear about Miles Franklin and My Brilliant Career (and Christos Tsiolkas is interviewed about Head On) but, for example, Kenneth Cook receives no credit for Wake in Fright (the novel is better than the film, and the film is Australia’s best!), nor does Joan Lindsay for Picnic at Hanging Rock, which turns 50 this year.

Let’s leave the last word to Weaver: “These days of the internet, too many bozos give their opinions and they’re so unqualified and they wouldn’t have a clue and they should just pull their heads in … But someone like David Stratton who’s seen thousands and thousands and thousands of films is entitled — and in fact it’s incumbent on him — to tell us what he thinks about them, because it comes from an educated place.”

Hear, hear.

David Stratton: A Cinematic Life (M)

4.5 stars

Q&A screenings with David Stratton in various states until March 7.

National release from March 9

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout