David Stratton remembers Cape Fear

I was on a ship migrating to Australia when I saw the director’s intended version of Cape Fear.

At the beginning of July 1963, the passenger liner Castel Felice sailed from Southampton, England, bound for Sydney, Australia, via Port Said, Aden, Fremantle and Melbourne. Of the 1400 passengers on board the vessel, probably half were Australians returning home after a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Europe while most of the rest were migrating to Australia — £10 Poms. I was one of those.

There wasn’t a great deal in the way of entertainment to keep passengers amused during the five-week voyage, but there was a movie every night. The films were projected on 16mm (rather than on the 35mm gauge used in cinemas at the time) and were fairly up-to-the-minute. Among them were the latest Carry On comedy, Carry on Cruising; a boxing drama with Anthony Quinn, Jackie Gleason and Mickey Rooney titled Requiem for a Heavyweight; and The List of Adrian Messenger, a very curious mystery movie made by director John Huston in Ireland in which several very famous superstars of the period — Tony Curtis, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra — made cameo appearances under make-up so heavy and complicated that they were supposed to be unrecognisable. Let’s just say the experiment was a failure.

The film that interested me most on the voyage was Cape Fear, the first movie made in America by the talented British director J. Lee-Thompson and about which there had been considerable controversy. I’d seen a version of it six months earlier in my local cinema, and was curious to see it again.

Cape Fear was based on a book, The Executioners, written by John D. Macdonald in 1957. It was filmed by Universal in 1961 despite considerable opposition from the Production Code, America’s non-binding censorship body. The problem stemmed from the theme of the material. Gregory Peck plays Sam Bowden, a lawyer who lives with his wife, Peggy (Polly Bergen), and 14-year-old daughter Nancy (Lori Martin), in a small town in Georgia.

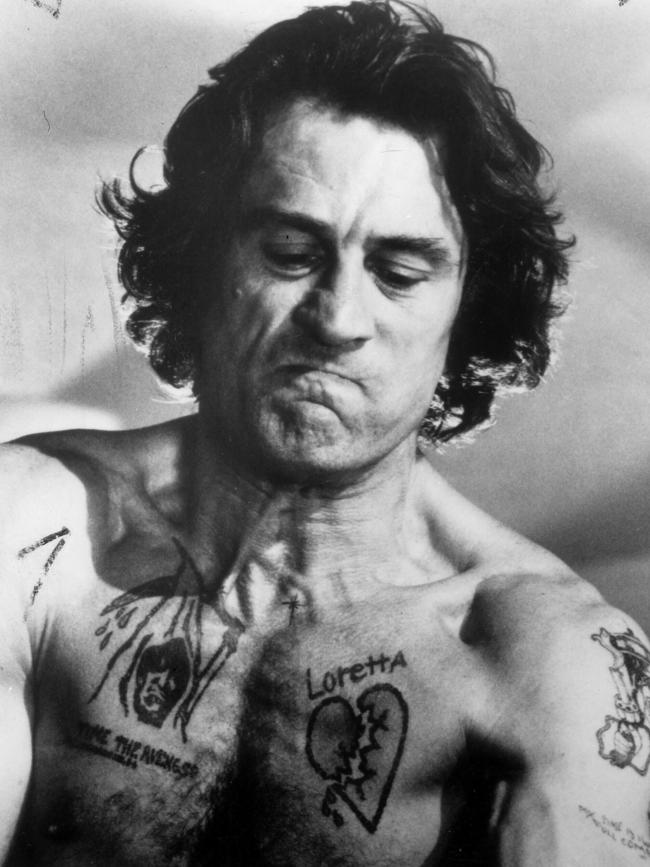

Bowden finds himself and his family under threat from Max Cady (Robert Mitchum), a brutal, illiterate criminal who has just been released from prison after serving eight years for rape. Cady is seeking vengeance because Bowden had testified against him in court. Cady begins to stalk the Bowdens, but Police Chief Dutton (Martin Balsam) is unable to arrest him because he hasn’t committed a crime.

The controversy arose because of Cady’s implied threats not only to Peggy, but also to Nancy. Before the film went into production the screenplay had to be approved by the code, and the word “rape” was deleted whenever it occurred. It was clearly combustible material, and the direction had to be pretty nimble to straddle a line in which the story’s confronting elements would be present without becoming so prominent that the film would be banned (or to put it more correctly, denied the seal of approval that would allow it to be screened in American cinemas).

It was Gregory Peck who suggested that Lee-Thompson be given the tricky job of directing. Peck had worked with Lee-Thompson on The Guns of Navarone (1960), a large-scale, star-studded British war film that had been a happy experience for all concerned. A stage actor and screenwriter before he directed his first film, Murder without Crime (1950), Lee-Thompson (whose name is sometimes spelt without the hyphen) had made a reputation as a creative director of films with a social message: The Weak and the Wicked (1953) had dealt sympathetically with women involved in prostitution, and the director virtually launched the late-1950s “kitchen sink” school of British cinema with Woman in a Dressing-Gown (1957) and No Trees in the Street (1958). He had also made a couple of fine thrillers about children who become unwittingly involved with a murderer (The Yellow Balloon, 1952; Tiger Bay, 1959) as well as one of the most suspenseful British war films, Ice Cold in Alex (1958). Arguably his best film is Yield to the Night (1956), an uncompromising drama set in a condemned cell where a murderess, played by Diana Dors, awaits her fate; the film was based around the story of Ruth Ellis who, in 1955, became the last woman to be hanged in England. After these achievements, as well as some lighter fare, Lee-Thompson rose to the challenge of his first Hollywood film with distinction, and Cape Fear is consummately made and genuinely suspenseful. The director’s collaboration with cinematographer Sam Leavitt to create an evocative world of light and shadow is particularly effective, as is Bernard Herrmann’s fine music score.

The 105-minute film was released in the US in March 1962 to wide, but not unanimous, critical acclaim. But the British Board of Film Censors was far from happy, and before the film could be released in the director’s home country months of discussion, negotiation and argument went by. Finally, Lee-Thompson went public, claiming, in an article he wrote for a London newspaper, that his film had suffered 161 censorship cuts. He also wrote a piece for the magazine Films and Filming (“The Still Small Voice of Truth”, April 1963) in which he revealed: “What interested me was the problem — which unfortunately (was) completely eliminated from the English version — of parents whose daughter is raped. Do they or don’t they accuse the rapist, because he will deny the crime. That means that the daughter has to go and give evidence … (and) she (will be) subject to a defence by the rapist … We had a very fine scene in which the husband … eventually convinces his wife … not to take the risk. This is a problem all over the world. Many rapists get away without being prosecuted because the parents won’t take the risk.”

The British version of Cape Fear, which finally opened in January 1963, ran for 99 minutes, six minutes shorter than the American version. Part of the reason for the concern of the censors was surely the savage intensity of Robert Mitchum’s chilling performance as Cady; Mitchum rarely played villains, but when he did (as in Charles Laughton’s masterly The Night of the Hunter, 1955) he was remarkable. Mitchum is well matched by Gregory Peck whose small-time lawyer and family man is not far removed from the similar character he played in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

Incidentally, when Martin Scorsese remade Cape Fear in 1991, with Nick Nolte and Robert De Niro in the leads, he found small roles for Peck, Mitchum and Martin Balsam. Lee-Thompson directed 30 more films during a long career, but not one achieved the successes of his early work up to and including Cape Fear.

The film screened on board the Castel Felice that July evening was, indeed, the complete American version, which, after all the fuss generated in England, came as a welcome opportunity for me to see the film as its makers intended it to be seen. The ship docked at Woolloomooloo in Sydney on July 29, and my life in Australia commenced.

The 1962 version of Cape Fear is streaming on iTunes.

READ MORE: COVID-19 lockdowns: exhibitions go online | David Stratton indulges in cinematic memories | Historical imbalance will finally be corrected

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout