Dancer Philippa Cullen’s fascinating legacy

Australian dancer Philippa Cullen, who died at just 25 after visiting an ashram in India, left a fascinating legacy

Philippa Cullen: Dancing the Music

McClelland Sculpture Gallery, until July 17

Philippa Cullen, who was born in 1950 and died so prematurely in 1975, was at once highly original and very much of her age. Her inclination to conceptual and non-commodified art was in sympathy with other minimalists and conceptualists of the same period: she disliked the reduction of dance to a highly-refined but remote performance without ritual or spiritual meaning, watched by spectators who were radically separated from its practice and physicality.

She longed instead for the kind of dance that expressed belief and embodied a shared culture, and where, even if there was still a distinction between performers and audience, the latter were physically closer and more involved as well as participating through sharing in the same world of belief. Speaking of traditional and tribal cultures, she wrote (1973): “In these societies dance plays a role for social activities such as birth, initiation, marriage and war. Dance is always a form of ritual, it has an object in view like sympathetic magic. Of course the main function of dance in these societies is religious … in request for rain and harvest, in exorcism of devils, in curing of the sick, in funeral ceremonies.”

The corporeality of her work was also of its time. Although she had trained in dance and ballet with Gertrud Bodenwieser since the age of eight, she was not drawn to the idea of perfectly trained and disciplined bodies working together in faultless harmony. Like other modern dancers and choreographers of the time, her work, as far as we can judge from the archival film footage – grainy and patchy even after digital restoration – displayed a mixture of spontaneous energy and entropic wilting.

Her own performances could apparently be both energetic and sensual, according to a contemporary review of her improvisation with the group AZ Music in 1972: “There were some wildly erotic phases in this dialogue between the lone female silhouette and four male silhouettes with instruments; at times it became almost an orgy of sexual celebration …” (David Gyger in The Australian, 18 April 1972). These were, after all, the years of the sexual revolution and women’s liberation, even though this dimension of her life is only hinted at elsewhere in the exhibition.

Cullen’s particular aesthetic relation to the body also has deeper roots than the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. Its real background is the mind-body dualism that was inherent in the modern scientific worldview although not, as is sometimes suggested, characteristic of western thought in general.

The ancient Greeks, like the Indians, knew that mind and body were intimately connected. In the ancient humoral theory of physiology and medicine which I described some months ago in connection with another exhibition – devised in antiquity and inherited by the Middle Ages and early modern period – four humours correspond in the microcosm of our bodies to the four elements that compose the macrocosm of the natural world.

But the humours explain both psychological and physiological phenomena, both health and character. And even the world of nature, composed of the elements, is not exclusively materialistic by subsequent standards: “yea plants, yea stones detest / and love”, as John Donne writes in A Nocturnal upon Saint Lucy’s Day (c. 1617). Even seemingly inert matter has some elements of volition, as everything seeks to find its appointed place in the order of nature.

It was only the new scientific outlook taking shape in the thinking of a younger generation that began to conceive of matter as radically inanimate: not only as incapable of volition but unable to move itself without the action of an external cause – as a billiard ball cannot move until it is struck. But the inanimate concept of matter raises questions about whether mind can act on it as a cause.

Descartes defines matter and mind in ways that make them not only essentially different, but so heterogeneous that it becomes virtually impossible to explain how they can communicate or interact in any way, even though commonsense tells us that they do so constantly. This was the origin of the mind-body dualism problem that plagued philosophers for the next century and provoked thinkers like Malebranche and Leibniz to come up with such elaborate and implausible theories to account for everyday reality.

But the hardline “materialist” conception of matter that appealed to many thinkers in the 18th and 19th centuries was subsequently undermined by a better understanding of the structure of atoms and in particular by Einstein’s suggestion of an ultimate equivalence between matter and energy.

Cullen’s most original idea as an artist was that dance should not be subordinated – or at least not completely subordinated – to music. In modern forms of dance as spectacle, it was entirely determined by the music, rather as the movement of the billiard ball is entirely determined by the energy imparted to it by the tap of the cue. This is why in her early works like Utter (1972) she had the dancers make sounds with their voices instead of using a soundtrack.

But then she came upon a device that inspired most of the experiments of the next few years of her short life – a device which in fact seems to show, as in Einstein’s theory, that the body is also made of energy. “I would define dance,” she writes in 1973, “as an outer manifestation of inner energy in an articulation more lucid than language.” And now she had found a way of manifesting that inner energy also in the form of sound.

This device was the theremin, named after the Russian Leon Theremin (1896-1993) who invented it just over a century ago; it had grown out of research into developing motion detectors or proximity sensors for security purposes, and Theremin himself had a long and colourful career between music – he was a cellist and explored the musical potential of his invention – and his work in intelligence, including bugging the American embassy in Moscow between 1945 and 1952.

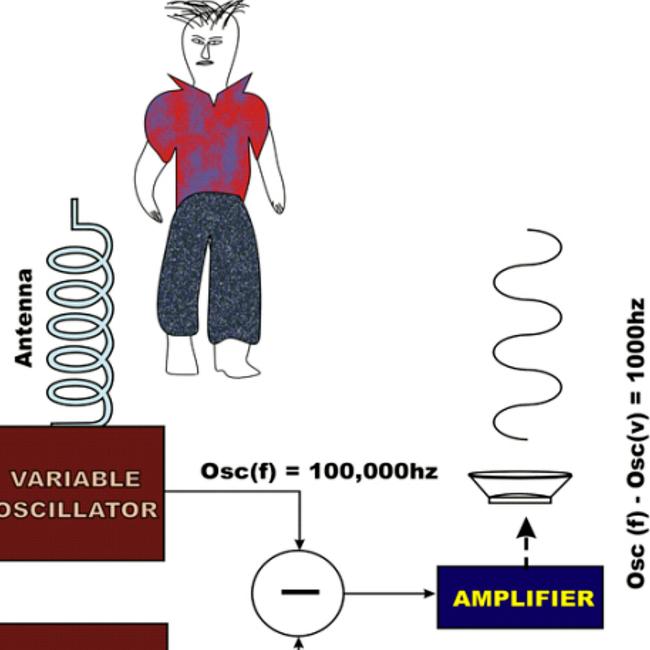

The theremin, as Cullen herself writes (1972) is “an electronic device which detects the capacitance of the human body and transmits a sine wave frequency which varies according to the proximity of the body to the aerial.”

The exhibition includes a working model which consists of a vertical antenna and a horizontal wire. As our hand or any other part of our body approaches these sensors, we begin to hear a dull grumbling at about a foot away, rising to a high whining pitch as we get closer. With a little practice we can vary both volume and pitch, and all without any physical contact with the instrument.

This invention had been used in musical performances since the 1920s and more recently in some modern dance experiments, especially by John Cage. But its musical range was clearly very limited; Cullen, with the help of technologically-minded friends at Sydney University, devised ways of using it in conjunction with the new electronic synthesiser technology to produce a far wider range of musical effects. The idea was that dancers would at last make their own music, produced from the very movement of their bodies, as detected by the theremin and enhanced by the synthesiser.

Clearly, however, it would be a long journey from the variable whining of a motion detector to anything like the multidimensional complexity of music, and Cullen recognised that it would at least be a long process. But perhaps more important than producing listenable music was the principle that the movement of a dancer’s body could generate patterns of sound.

These experiments led to the performance Homage to Theremin II, held at International House at Sydney University in 1972: one of the best documented sections of the exhibition, including diagrams of the detecting devices and numerous photographs of Cullen and her dancers playing with theremins that now take the form of metal coils and loops, presumably to detect movement in more directions.

In later work she also experimented with pressure-sensitive floors, again capable of translating corporeal movement into sound patterns. And she was interested in other ways of producing sound with the body, including with the breath or heartbeat. There is an intriguing article (undated but probably from 1974) in which Geraldine Pascall talks about her use of ECG and respiratory monitoring devices: “She stood still for a moment, did strange things with her breathing and one of the bright dots began tracing a different patter … the deep roar subsided into an eerie melody that was almost familiar. Miss Cullen was playing a tune with her respiratory monitor.”

Apart from Cullen’s interest in technology, the exhibition documents other activities that are somewhat less distinctive and more characteristic of the generic counterculture of the time, such as unstructured dance classes, if that is the right word, in the Quad at Sydney University, public dance interventions, and a 24-hour collective performance involving other performers and participants.

In 1972, Cullen won an Australia Council grant to travel to Europe where among other things she worked with the composer Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, who became her lover. On the return voyage she stopped in India and visited the ashram founded by the famous yogic master and spiritual teacher Sri Aurobindo (1872-1950) at Auroville, near the old French city of Pondicherry in Tamil Nadu. She had travelled to India again to spend some months at the ashram in 1975 when she became ill and died of complications after an emergency appendectomy.

It may seem incongruous, if we think of science and spirituality as antithetical, that someone so involved in technical experimentation and obsessed with the new possibilities of electronic engineering should be drawn to the contemplative life of an ashram. But apart from the fact that breath and breath control – which were clearly of great interest to her – are central to yogic practices, there is the crucial if seemingly paradoxical fact that science, in its more sophisticated forms, is not materialistic in the old reductive sense of the 18th or 19th-century materialist doctrines.

Science has never really presumed to answer ultimate metaphysical questions, and indeed the early theorists of science, like Bacon, were quite clear that their aims were more modest, empirical and utilitarian. Scientists can therefore be, and in practice are, either theistic, atheistic or agnostic.

As already suggested, Einstein’s revelation of the equivalence of matter and energy particularly undermines the old deterministic materialism. And Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy, rooted in ancient Indian tradition but also informed by his studies at Cambridge, although a vast subject and expressed in voluminous writings, seems to be centred on a conception of spiritual evolution towards higher consciousness. There does not seem to be any clear statement by Cullen about what she was seeking at Auroville, but it is plausible to imagine that she sensed the affinity between a conception of spirit that is also embodied, and a conception of energy which transcends reductive materialism.

Philippa Cullen: Dancing the Music

McClelland Sculpture Gallery, until July 17

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout