Clarice Beckett’s paintings were discovered in an open farm shed

Victorian artist Clarice Beckett was the only painter who could make cars into poetic objects. And we have one woman to thank for saving her work from ruin and showing it to Australia.

Clarice Beckett’s work is easier to like than to understand. Her small pictures are engagingly fresh and spontaneous even when they can sometimes appear casual or unfinished. Her story is touching: the talented young woman from a well-to-do family who is free of material concerns but constrained by her sense of duty to ageing parents, who never marries and dies young, debilitated by grief at her mother’s death but also a victim of her own devotion to plein-air painting in all weather conditions.

There is the pathos, too, of the loss and recovery of her reputation; though well-regarded in her time, she died too young and, like other women painters of the inter-war years, was eclipsed by the dominant post-war figures of Nolan, Tucker, Boyd, Dobell and Drysdale. Her work was notoriously stored in an open-sided shed in the country, where much of it suffered irreversible damage from the weather, by a family who did not appreciate its value. It was rediscovered almost by chance by art collector and gallerist Rosalind Hollinrake, who was then married to Barry Humphries.

Since then, Beckett has received considerable attention, most recently with the beautiful monographic exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia in 2021 (reviewed here on March 27, 2021). But her work cannot be understood without taking account of the method she learnt from her master Max Meldrum, and fortunately there has also been a renewal of interest in his work and that of his pupils in recent years.

The AGSA, some years ago, presented a survey of the school under the title Misty Moderns (reviewed here August 30, 2008), and more recently Ballarat Art Gallery’s Light and Shade (reviewed here June 18, 2022) was another opportunity to ponder the real meaning of the Meldrum method.

The present exhibition at Geelong is an appealing one in general and offers a good selection of her work, but it does not contribute greatly to a deeper understanding of her oeuvre. Someone – whether carried away by the fashion for immersive experiences or the fad for AI – has devised an “Atmospheric Lab” in which visitors can choose a locality and find themselves surrounded by projections of digitally blurred photographs of that site.

A populist installation like this, though obviously aimed at the less visually sophisticated, could still be acceptable or even useful if it gave viewers some inkling of what is really going on in the work; but the “Atmospheric Lab” is actually misleading, because Beckett’s pictures are not merely the result of making things blurry or fuzzy. They are not even explained by the phenomenon of aerial perspective, which makes both colour and tone less distinct in the distance.

The other misleading element in the exhibition is addressed to more educated viewers. One of the labels quotes a well-known Australian art historian as “identifying” Beckett’s “layered tonal gradations as precursors to the 1950s-60s abstractions of … Mark Rothko.” On the other side of the room this becomes “various art historians” who have considered Beckett as prefiguring “the hovering, luminous colour fields of Mark Rothko.”

There is of course no chance whatsoever that Rothko could have known the work of Beckett, and it is highly unlikely that he was influenced by any other Meldrumites. More importantly, Rothko’s aims and orientation were diametrically opposed to those of Beckett and Meldrum, who were devoted to a certain concept of optical realism. The fallacious association with Rothko seems to be a relic of the mid-20th century modernist myth that all modern painting was on a teleological path to the endpoint of abstraction.

Any deeper appreciation of Beckett starts with an understanding of Meldrum’s method, which the artist himself explained at length in his book The Science of Appearances (1950). Meldrum despised both academic and impressionistic forms of realism, believing that the only truly scientific realism was based on seeing a subject as a single and whole form, in which tonal relations were the most important structural factor.

From this derives the most distinctive aspects of the Meldrum method. As Arnold Shore wrote in 1916, “Up as close as possible to the subject went our easels. Back 20 feet or more we were led. Half close your eyes. Compare the effect of the subject with your canvas. What do you see? … We were forbidden to look at the subject when close to it, all our observations must be made from the viewing point 20 feet away.”

I quote this passage again because it sums up two complementary aspects of the system, which I have actually had the opportunity to see in practice: the placing of the canvas close to or preferably alongside the subject, and the discipline of viewing the subject from a distance at which it can be seen as a single visual form. The first view from such a distance will of necessity be very generalised and rudimentary. As Meldrum explains in his book however, the painter is then allowed to come forward in a series of stages, each time recording the further discriminations that can be seen from that distance, but stopping at a point at which the motif can still be comprehended as a single form.

How is this method applied or adapted to landscape, and perhaps particularly to Beckett’s seascapes? The canvas cannot be placed literally beside the view, and the artist will not be walking back and forth in the same way. But the fundamental principle of the single act of seeing is preserved, and one of the consequences this entails is that the whole picture will be seen at a single focal length.

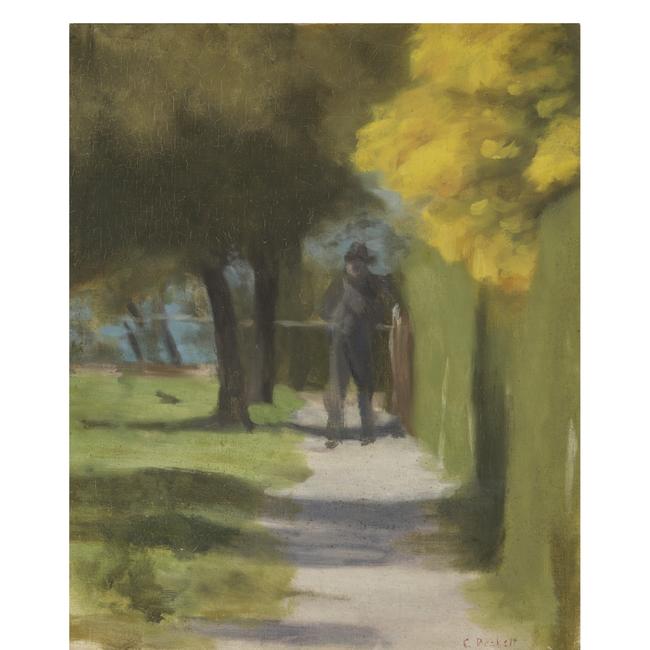

With Beckett’s seascapes, there is usually a focus on infinity, which means an open setting where everything at a certain distance will be in focus, but things in the foreground, if they appear at all, will be out of focus. Most painters, in looking at a landscape, would adjust their focal length to look successively at things that are closer or further off, but that is prohibited by the Meldrumite requirement for optical unity. And this explains why the foreground trees in Dusk (c. 1928) are so loosely defined: it has nothing to do with “atmosphere”, but represents the way these forms look when the gaze is focused beyond them in the far distance.

Another effect of the single act of seeing is conspicuous in Spring Morning (c. 1925). The dark shadows appear exaggerated because in the normal course of perception the eye adjusts the aperture of the pupil as it looks at brighter and darker parts of the scene, so that what we effectively “see” is a composite of multiple separate glances; here, however, following Meldrum’s principles, the whole thing is seen as though with a single light exposure setting, resulting in dramatic contrasts of light and dark. This phenomenon is less visible elsewhere because of Beckett’s preference for dawn or evening as times to paint.

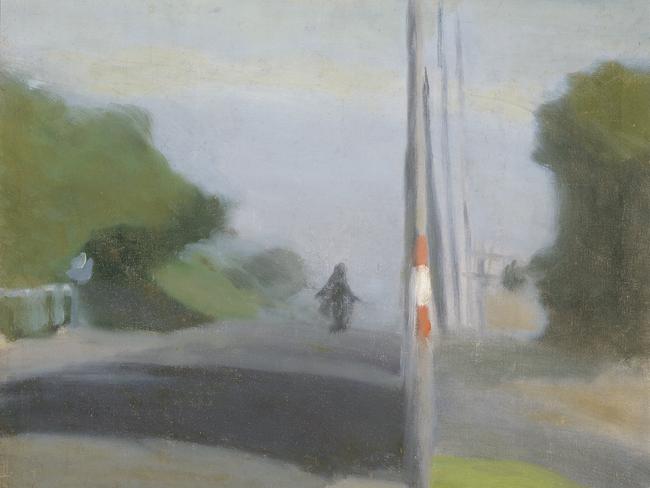

We can understand the elements of Beckett’s process in a painting like Wet Evening (c. 1927). The ideal viewing distance for this picture, that is the point at which the image is both whole and in focus, is perhaps a metre or more, which means that this was also the artist’s painting distance. This also determines the virtual frame for the motif itself, which is much further off; in other words the view in the painting represents what could be seen through a frame of the painting’s dimensions from a distance of 1m or a bit more.

Such a use of the frame, even if only virtual and conceptual, reinforces the sense of what in the Renaissance was called the intersection of the visual field. In this case the artist tries to give an account of exactly what is to be seen through the frame as a unified visual experience. This is why, although the light conditions are far more subdued than in Spring Morning, the framing trees and the house in the background are all cast into the shadow. More detail could be seen by looking into the shadow, but that would compromise the tonal unity of the whole.

These are the principles of the method that gives Beckett’s work its unique tonal harmony, but they do not fully explain her sensibility. The Meldrum method is an infrastructure that she has in common with the best of his other pupils, but Beckett adds to it the specific poetic qualities that have made her work so distinctive.

The first of these is her preference for dawn and dusk as times for painting. It is often said that she brings colour to a system that, in Meldrum’s original formulation, was austerely tonal. There is some truth to this observation, although Meldrum and others did in fact use colour at times; but what is above all significant is her preference for the times of day when, with the first appearance of light or its gradual disappearance, colour is just beginning to be visible or is just fading into the monochrome of twilight.

She is thus indeed interested in colour, but above all in its liminal states, as it emerges from tone: this is not a break with Meldrum’s teaching but an insightful and imaginative extension of his fundamental principles, and it is interesting that he held her in high regard in spite of his tendency to be sceptical about women painters.

But Beckett’s interest in dawn and dusk extends to broader moral and existential sense of the world: she is drawn to the awakening of human life – to images of fishermen pushing their boats out into the bay at first light – and to its settling at the end of the day, with cars driving home in the dusk. She was indeed, as I have observed before, the only painter who could make cars into poetic objects, and the same could be said of telephone poles which, for a woman used to melancholy solitude, are like magical lines of communication that connect absent friends.

Finally, the most remarkable aspect of Clarice Beckett’s painting is that each work is clearly a single, radically plein-air study of a transient moment of experience. Some were probably painted in slightly longer sessions than others, and are thus more “finished”, but it is hard to believe that she reworked them much, if at all, in the studio, or even that she returned for a second session on the same picture.

This is why some pictures appear slight, or unfinished, or simply less successful than others. They were primarily, as I suggested before, notations of a daily act of visual meditation. No doubt only those that came together into a satisfying whole were selected for exhibition, while the others remained as records of a regular and almost spiritual practice which, in the absence of any kind of documentation, must remain tantalisingly speculative.

Clarice Beckett – Atmosphere, Geelong Gallery, until July 9.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout