Christopher Allen reveals art’s mysterious secret sexual codes

Images of love are never overtly sexual, but there are erotic overtones if you pay close attention

The most enduring contribution the Greeks made to the history of art was to conceive of the human body as beautiful. The effect of this new idea, first expressed in the formal figures of the Archaic kouros and then evolving into the synthesis of real and ideal represented by classical art, was so profound that we have long taken it for granted and find it hard even to recognise its profound originality.

Humans experience sexual attraction to other bodies; but this natural and instinctive response has little in common with the disinterested admiration of form. The human body can be sexually attractive, unattractive or even repellent, yet all of these are appetitive responses, representing degrees of desire, indifference or aversion. And that is how it is most often represented: as desirable, powerful, comically grotesque or pitiful.

Sophisticated cultures do indeed possess a higher and more refined conception of human beauty that is expressed in their literature and their art. But it tends to focus on the face: it is regularity of features, brightness of eyes, redness of lips, clarity of complexion, abundance of hair that are praised. When the body is mentioned it is only in general terms: tall, slender, swift, agile, and so on – essentially references to youth and health.

What appears with the kouros figures of the Archaic period, in the seventh and sixth centuries BC, is something very different. The early Greek sculptures began with the model of the human figure developed by the Egyptians, but modified it in three important ways: they were anonymous or generalised bodies, not portraits of monarchs; they were freestanding, not engaged in blocks of stone; and they were naked rather than clothed. Thus they became universal images of man, they stood on their own feet, embodiments of autonomy, and they fully accepted the body instead of considering some parts as shameful and to be hidden.

The Greeks thus conceived of the beauty of the body as something distinct from, even if partly coinciding with, its desirability: the beauty of the human figure became the symbol of the dignity of man, the physical emblem of what we call a humanistic outlook. It is no accident that this idea emerged in art – and developed from schematic, almost conceptual formality to increasingly naturalistic and fluid harmony – at the same time as the beginnings of philosophy, grounded in confidence in human reason, and of new political ideas grounded in the belief in human capability and responsibility.

This idea of the beauty of the human body, with its powerful symbolic associations, was enthusiastically rediscovered in the Renaissance, and we can feel the delight with which sculptors from Donatello to Michelangelo explore the expressive potential of the figure. But the classical sensibility did not penetrate to the same degree into the northern parts of Europe; one of the fascinating aspects of Albrecht Duerer’s development is to see how this brilliantly talented northerner strives to assimilate the classical forms of Italy, like someone learning a foreign language. For others, like Albrecht Altdorfer, it is an incomprehensibly alien one.

The Flemish, as we saw a few weeks ago, had always loved the detail of physical appearance and corporeal reality; theirs was a world of flesh that always seemed tinged with vulgarity to the more intellectual and abstract way of thinking of the Italians, and later of the French after they had assimilated the Italian tradition – which is why the first true modern academy of art was established in Paris in 1648 and really began to function properly in the 1660s.

Rubens was part of that Flemish world, and his work was regarded by many at the academy in Paris as fundamentally inimical to its ideals, but he became a great artist by a lifelong effort to understand the Italian tradition, from Raphael and Michelangelo to the artist who was his closest model, the Venetian Titian. And one reason for Rubens’s deep engagement with Italy was that Flanders belonged to the same world of Catholicism, as it had now become since the Reformation in the 16th century.

The northern part of the old Netherlands – united as part of the Duchy of Burgundy at its apogee in the 15th century – had adopted the beliefs of the reformers and had broken away from its Spanish masters, the successors of the Burgundians.

The Dutch, like other Protestants, disapproved of religious imagery, but fortunately for the history of art they also had a remarkable love of painting: contemporary pictures show oil paintings even on the walls of quite modest homes and shops. And so landscape, still life and portraits all flourished in the Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century.

As for the human figure, however, Dutch painters – other than those who went to live in Italy – were barely touched by the classical idea of its beauty and dignity. Rembrandt was the product of this world: he is unrivalled in his understanding of the pathos of mortal flesh and the mystery of inner life, particularly in his portraits and the self-portraits that he painted throughout his career, in a uniquely frank and progressively unfolding autobiographical meditation.

But Rembrandt gives no hint that he ever thought of the human body as a thing of beauty. When he paints the cadaver of Christ being taken down from the cross, it is as limp and inanimate as a dead animal. The great painting by Rubens that he had in mind and to which this is a kind of reply echoes the figure of the Laocoon in the dead Christ, thus evoking the heroism of the Trojan priest’s sacrifice and the grandeur of antiquity while changing a body tensed in the paroxysm of struggle into one that has collapsed in death.

There are important sexual themes in Rembrandt’s work, such as his great Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654), compositionally echoing Annibale Carracci’s Venus and Anchises (in turn indebted to an ancient relief that Rembrandt also could have known from a recent publication), but his emphasis is on the moral and psychological dimensions of the action. Bathsheba has just read a letter from King David and realises that her life will never be the same; we know, although she does not, that she is destined to bear his son and be the mother of King Solomon.

In other paintings, such as Susanna and the Elders (1647), a subject usually treated with erotic ambivalence – at the very least as an excuse to paint a beautiful nude, with overtones of voyeurism and exhibitionism, even if the voyeurs will be punished in the end – becomes simply a picture of old lechers spying on a plain girl. He has even less sympathy for homoerotic themes: Jupiter ravishing Ganymede becomes an eagle carrying off a screaming toddler who urinates in fright.

Some of his engravings have explicitly sexual themes, like a graphic yet awkward image of fully clothed coupling in a cold country, but they are far from erotic. His most moving images of love emphasise its affective rather than physical dimensions, such as the trusting tenderness of husband and wife in The Jewish Bride (1665-69).

Vermeer’s images of love are much more elusive; never overtly sexual, and seldom even explicitly romantic, many of the tiny number of pictures by his hand – only 34 – nonetheless include subtle allusions to love and desire. Just in the past few months his Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657-59) was unveiled after a lengthy period of restoration that revealed a painting hanging on the wall in the background. There is nothing inherently surprising about this, since many of Vermeer’s compositions have other paintings hanging on the walls of interiors; but in this case it is a very large picture of Cupid with his bow, clearly telling us that the letter she is reading is from a lover.

Occasionally, Vermeer will represent a man and woman together, but he seldom allows us to see both their faces. In Officer With a Laughing Girl (c.1657), for example, the officer of the title dominates the foreground but is little more than a silhouette: the girl in the background faces us, smiling at him but dwarfed by the effect of perspective; she seems vulnerable and we are not able to judge the sincerity of her lover, with his red coat and attitude of swaggering confidence. In The Music Lesson (c.1662-65), it is the man’s face we see, while the girl turns her back to us, concentrating on her playing.

Vermeer often prefers to imply a relationship that can be suggested, as in The Music Lesson, through the metaphor of playing music together. In Lady Standing at a Virginal (c.1670-72), an empty chair in the foreground evokes, as so often in art, the absence of a person. The woman’s gaze, as she looks up and towards us, implies that he just may have entered the room; the romantic or erotic theme is confirmed by the presence on the wall of the same painting of Cupid that has just appeared in Dresden.

In Lady Seated at a Virginal (c.1670-72), the young woman again looks up at us as though we were in the place of the expected lover, and the prominent viola da gamba in the foreground alludes to the music they are about to make together. The painting on the back wall is Dirck van Baburen’s The Procuress (1622), in which the girl whose services are being procured by the old crone on the right is playing a lute, confirming the sexual connotations of musical performance.

Erotic themes are thus pervasive, although subtly evoked, in these pictures, and Vermeer’s preference for allusion and suggestion is even more clearly illustrated by the number of paintings that employ the motif of the letter.

There are pictures of young women reading a letter that a maid has just brought, or writing one that the maid is waiting to deliver to the lover. But perhaps the most interesting of all are those that represent the reading of letters: these compositions epitomise what is perhaps the most intimate and the deepest part of Vermeer’s sensibility, which is his feeling for attention.

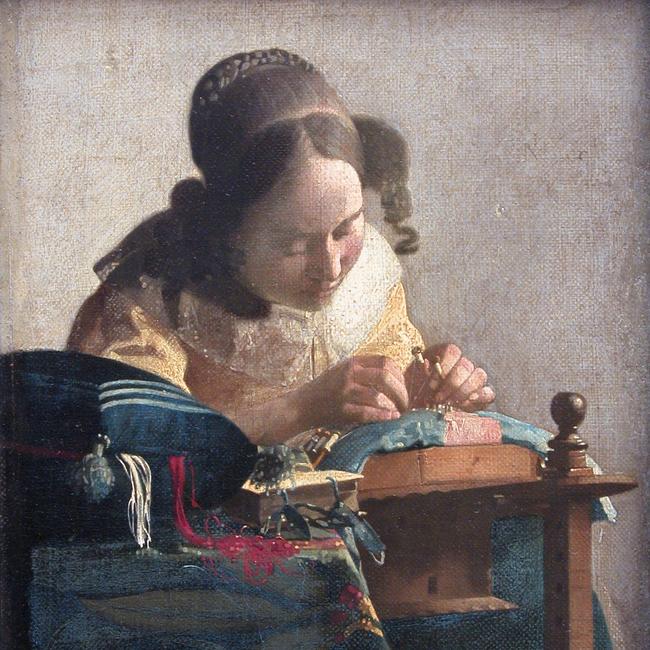

There are few other artists who look at the world with the same sort of attention, and fewer still who take attention as their subject: in his The Lacemaker (c.1669-70) or Woman Holding a Balance (c.1663-64), Vermeer depicts the perfect stillness of the mind intent on a single task; his pictures of reading have the same inwardness and focus. Nothing indeed better captures the difference between his sensibility and that of Rembrandt than the way they represent the theme of the letter: Vermeer’s Woman Reading a Letter (c.1662-63) is entirely absorbed in the activity; Rembrandt’s Bathsheba has already read her letter and now she gazes away into the distance as its consequences ripple through her imagination.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout