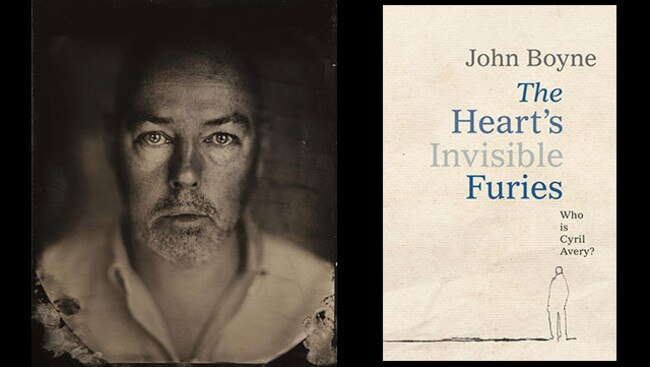

Catholic Church faces John Boyne’s gaze on gay, women’s rights

John Boyne’s new novel traces the recasting of Ireland’s attitude towards homosexuality.

The opening paragraph of John Boyne’s The Heart’s Invisible Furies sets the tone: “Long before we discovered that he had fathered two children by two different women … Fr James Monroe stood on the altar of the Church of Our Lady, Star of the Sea … and denounced my mother as a whore.”

It’s 1945. The “whore” is Catherine Goggin, 16 and pregnant. Cast from her village in the west of Ireland, she travels to Dublin, where she finds lodgings and a job in the tearoom of the Irish parliament. She gives birth to a boy, immediately offering him up for adoption.

The boy is taken in by the Averys: Maude, a literary novelist who spurns popularity, and Charles, a fraudulent banker. They name him Cyril (after a much-loved spaniel) and regularly remind him that he’s “not a real Avery”. His is a childhood marked by “money and status”, but the Averys are indifferent parents and their “deficiency” of love sets Cyril on a path towards “isolation and disaster”.

Aged seven, Cyril meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. For Cyril, the attraction is immediate, and when the boys meet again at boarding school seven years later, Cyril is unable to subdue his sexual fantasies. Having thoroughly imbibed the teachings of his Jesuit masters, Cyril recognises his growing fixation with Julian as “one of the most venal of all sins”. He prays, “please stop me from being a homosexual”.

Moving into adulthood, Cyril does his best to comply with social expectations. He visits a doctor in the hope of finding a cure for his homosexuality (you can’t be a homosexual, the doctor tells him, “there are no homosexuals in Ireland”). He takes up with a God-fearing girl and affects a romantic interest in her. But he is unable to tame his desire. He frequents the dark, hidden corners of the city, having sex with anonymous men, all the time troubled by a dread of discovery.

Boyne’s new novel spans 70 years. It maps Cyril’s life against cultural and historical shifts (the end of World War II, the advent of the Beatles, AIDS, 9/11) and traces the recasting of Ireland’s attitude towards homosexuality, from its classification as a criminal offence to the 2015 referendum that saw same-sex marriage legalised.

The impression is that of a country misshapen by an oppressive church working in lock-step with a cringing political class: a constitutionally recognised relationship that saw social conservatism and sexual repression driven into every corner of Irish life. And what Boyne is at pains to emphasise is not only the degree to which both women and gay men were denied legal and moral equality, but also the way in which that denial shaped, even distorted, their lives.

He has tackled similar themes before. In The Absolutist he explored the tragic consequences of suppressed homosexual desire, and in A History of Loneliness, a novel about sexual abuse, he exposed the deceit and complicity of the Catholic Church. The Heart’s Invisible Furies augments the anger and frustration of those books, but eschews their more sombre notes, opting instead for something lighter.

Boyne makes humorous use of Cyril’s eccentric family, and there is a hyperbolic reality that is reminiscent of John Irving’s best work. There are laugh-out-loud moments (Cyril in the confessional admitting to his “sin”; a doctor urging Cyril to visualise Warren Beatty before jabbing his testicles with a needle) and satire that bites: “It was 1959, after all. I knew almost nothing of homosexuality, except for the fact that to act on such urges was a criminal act … unless of course you were a priest, in which case it was a perk of the job.”

There are times, however, when the comedy is stretched to breaking point. Scenes run on longer than necessary and some characters are never allowed to rise above the level of an authorial joke. The effect is an uncomfortable tension between what seems real and what’s discernibly artificial, undermining the authenticity of Cyril’s predicament.

Boyne’s strength as a writer is how he allows his characters to grapple with the moral dimensions of the worlds in which they find themselves. When he plays to that strength, he creates for Cyril some beautifully affecting moments: a conversation with Catherine Goggin, neither aware of the other’s significance, in which he reveals his homosexuality; his first experience of sex in a bed; a farewell to Julian; his strangled attempts to explain himself to Alice, the woman he’s about to marry.

But for all the ground Boyne covers there’s something here that feels unfinished. He only fitfully explores the intricate relationship between Cyril and Alice, and the close parallels between their lives. And while he marks out the church and its tame politicians as the architects of much of the misery both women and gay men endure, he doesn’t explicitly account for their waning influence.

If there’s any suggestion here of where the impetus for change in Ireland might have been seeded, it’s Goggin’s parliamentary tearoom. Under her supervision, it becomes a place where the authority of neither priest nor politician holds any sway, and where common sense and compassion are thereby given the necessary space to breathe.

Diane Stubbings is a writer and critic.

The Heart’s Invisible Furies

By John Boyne

Doubleday, 608pp, $45 (HB), $32.99 (PB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout