Beyond a yarn into artistry: Bruce Pascoe’s Salt

In his new book, Salt, the Dark Emu author creates a mood that is earthy, tender and wry.

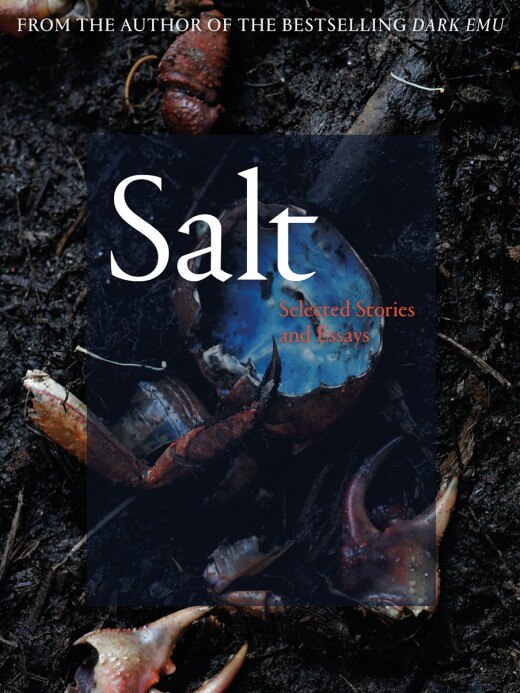

If you know Bruce Pascoe’s name it’s probably because of Dark Emu, his bestseller that exploded the myth that Australian civilisation began with the British. But Uncle Bruce was writing and publishing for decades before he turned our idea of Australian agriculture sideways. His new book, Salt, brings together the finest of his lifetime’s work. It contains 10 new short stories along with some previously published gems, and some of the best essays on Australia I ever hope to read.

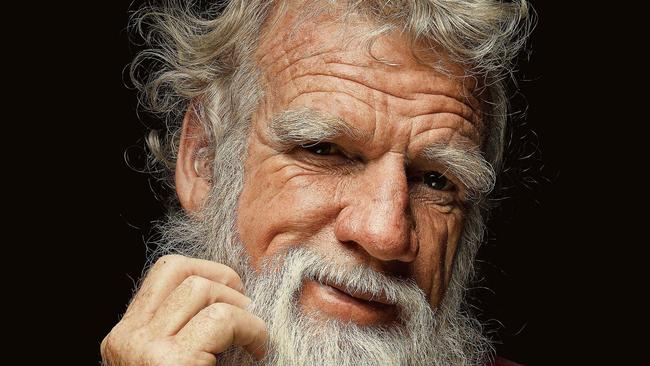

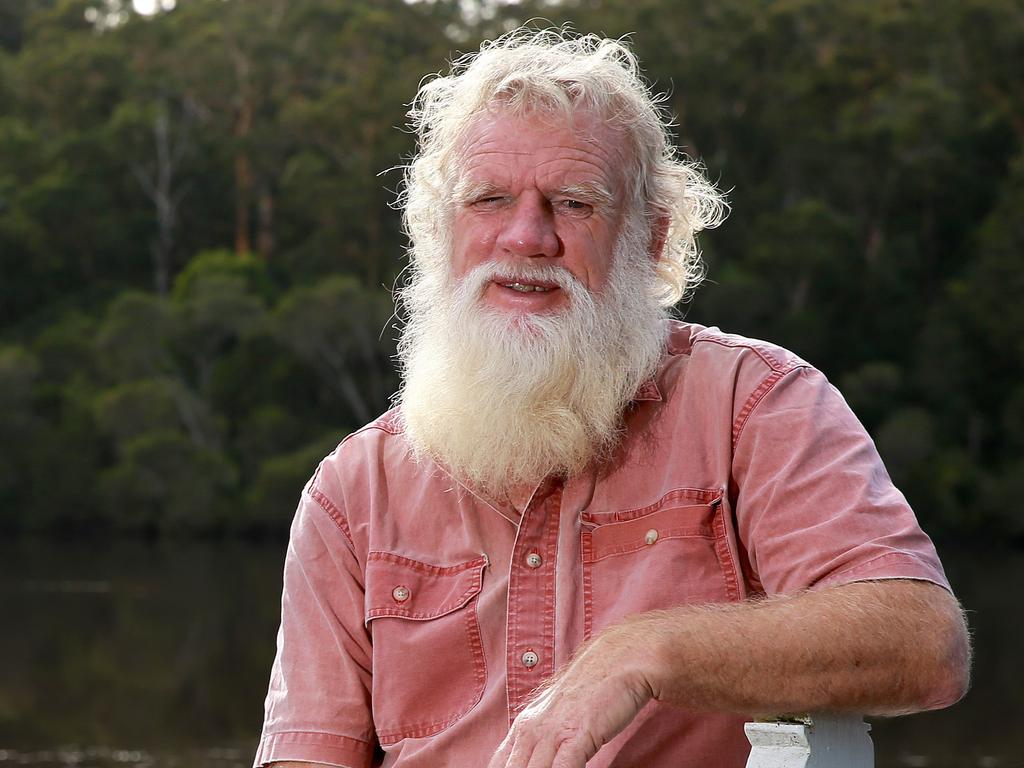

We might pause to ask what is a short story, anyway? Is it a yarn by another name? Some of the pieces in this collection are definitely yarns. You can imagine the author with his boot on a five-bar gate, narrating them with a dry chuckle from behind that beard of his. Anyone with a grandparent denied a formal education will recognise their ancestor in Thylacine, a heart-wrenching portrait of an uneducated man — “just a bushman” — encountering, and in awe of, a Tasmanian tiger, without much language to convey the experience. Like the bullying sceptic in the story, though, Pascoe knows “how to use words like the whipping end of a roll of barbed wire”. And it’s that whipping end of barbed wire that takes his short pieces past the yarn into the realm of pure artistry.

The mood throughout Salt is classic Pascoe — earthy, pragmatic, tender and wry. There’s a humility in this collection that doesn’t absent the author entirely but places him well towards the back of the crowd. Look, he gestures to his reader, see that bloke over there, have you noticed what he’s doing on the other side of the paddock? Pascoe takes many things seriously — abalone fishing, for one, and women’s beauty; the terrible cost of rural suicide, and the inner thoughts of crayfish — but he always takes himself with a large bucketful of salt. He is probably the most self-effacing writer we have in Australia, which is not a bad trick in a man with so much to say worth hearing.

A good short story is a track winding through new country you come to know as you travel through it. But a great short story is a track taking you across country you think you already know, only to discover you really had no idea where the hell you were. Some of the pieces in Salt are jaw-droppingly good in this lead-you-to-the-edge-of-a-cliff way. The last paragraph of Choosing made the back of my eyes prick with hot tears. So did A Letter to Barry, which leads the collection, and Big Yengo, where Pascoe recounts the feeling, proud yet discombobulating, of his adult son teaching him deep Aboriginal culture — “Who’s the big man now?” It’s a mystery to me why Lament for Three Hands isn’t on every high school curriculum in the country. Well, perhaps not that much of a mystery. It rightly won a massive national prize some years back and covers some of the same ground as Dark Emu, but in brief, allegorical form.

Not all the choices in Salt make for tears. There’s plenty of dry humour, which you’d expect. In the Arnhem Land town of Maningrida, Pascoe recalls bureaucratic racism in full flight: “The tough lady administrator is laying down the fiscal law to a grandfather whose exclusive right it is to tell five-twelfths of the Dog Dreaming. She can add up and he knows the workings of the universe.”

There’s tenderness and longing and a dash of lust in the way Uncle Bruce talks about the women of Maningrida. But as he reminds us in Sea Wolves, his is a matriarchal culture “where men cannot speak without first saying the words Bingyadyan gnallu birrung nudjarn jungarung: we arise from the mother’s heartbeat”. It’s a declaration of the primacy of women.

Pascoe’s Koori lens is obvious in those essays that continue the work of Dark Emu, explaining how the Australian continent has and can still be farmed sustainably. Or showing how Australian historians have been wrong, and why. There are also stories touching quite clearly on Aboriginal lore, like Whale and Serpent, that no white man could possibly have written.

Some of the stories stopped my breath. In Dawn, Pascoe tells of his love for his wife at the same time as he shows us what the nuts and bolts of Aboriginal worship of the feminine really look like. This worshipping of the woman in the story — slow, deliberate, reverential — is contrasted with another ceremony, to devastating effect. But there’s nothing cruel or dismissive in what he does, or indeed in any of the stories here.

This collection is a work of faith and love. Somehow Pascoe’s great democratic heart hasn’t given out; somehow, he’s still got it in him to believe that Australia can come to honour all its people, and all its true history, and make things right. After a lifetime’s dedicated work, he presents us in Salt with a stunning manifesto. The path is ready to be walked, but the trick is understanding how much we still have to discover about a place we think already know.

Melissa Lucashenko’s Too Much Lip won the 2019 Miles Franklin Award.

Salt

By Bruce Pascoe. Black Inc., 320pp, $34.99

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout