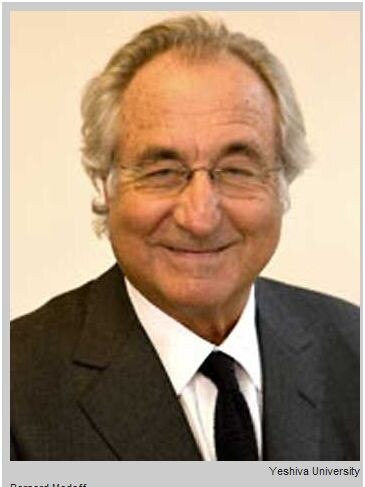

Bernie Madoff: evil genius or common crook?

Bernie Madoff: the man behind the $US68 billion Ponzi scheme remains a mystery. So is he an evil genius or common crook.

By my count, there are about a dozen books written about the life and crimes of Bernie Madoff, the ultimate fraudster who every other fraudster is now compared to. Journalists, private investigators, a prison cellmate — even satirist Andy Borowitz —have weighed in on the infamous Ponzi schemer since his arrest in 2008.

Which means if there is going to be another Madoff tome, there must be something new to offer. Did Madoff have accomplices we don’t know of? Was his entire family in on his scheme? Is there a buried treasure chest somewhere in the Cayman Islands filled with billions in Madoff’s stolen loot?

Richard Behar’s account in Madoff: The Final Word doesn’t fulfil this mandate. I don’t say this lightly. Behar is a well-regarded veteran investigative reporter. He tells us The Final Word was 10 years in the making. He draws on more than 300 interviews. He spoke and corresponded with Madoff at length, visiting him at the federal penitentiary where he was housed until his death, in 2021, at the age of 82.

Unfortunately there is little in this telling that hasn’t already been covered or raised before in books, documentaries and even a movie in which the disgraced financier was portrayed, somewhat awkwardly, by Robert De Niro.

Ponzi schemes are among the most simple of crimes, in theory. The trick is to keep attracting new investors, stealing their money to pay those cashing out their phony returns. That Madoff kept it going for years without conducting a single trade, creating fake account statements while maintaining a small support staff, is a testament to his evil genius. His clients included people like the “real estate baron Mort Zuckerman; Baseball Hall of Fame hurler Sandy Koufax; actor John Malkovich; film director and producer Steven Spielberg; New York Mets co-owner Fred Wilpon; entertainment mogul David Geffen; Larry Silverstein, developer of the rebuilt World Trade Center.” Even Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel fell for the con, as did charities and scores of average Joes saving for retirement.

As Behar recounts, in 1960 Madoff created Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, which grew to include a market-making and proprietary-trading operation that once accounted for 8 to 10 per cent “of the total volume of equities bought and sold on the New York Stock Exchange”. Madoff helped pave the way for the true competitor of the NYSE, the Nasdaq Stock Market, and later served as one of its chairmen.

His side-hustle investment firm operated largely in the shadows, tucked away on the 17th floor of the Lipstick Building in Midtown Manhattan. Following tips and newspaper accounts of the investment fund’s growth and Madoff’s fantastical record of steady returns, regulators investigated but always walked away from charging him. Without guidance, most of his investors regarded Madoff as a savant. That is, until the fraud came crashing down during the 2008 financial crisis, when Madoff couldn’t keep pace with the level of redemptions to meet his phony gains.

Behar, like many people who have looked into the Madoff saga, is sceptical the crime wasn’t a bigger conspiracy. As the story goes, Madoff confessed to his sons, Andrew and Mark, who turned their father in to the authorities in December 2008. The two siblings ran Madoff’s market-making and proprietary-trading operation with their uncle Peter. The children weren’t charged, even though Irving Picard, the court-appointed trustee subsequently tasked with recouping some of the stolen funds, believed that they knew, or at least should have known, of the fraud. Picard continued seeking to recover money from Andrew and Mark even after they died.

Behar points out that while market-making is regarded as the legitimate side of the family business, it haemorrhaged money and was being subsidised by funds siphoned from the investment arm. He quotes John Zach, one of the federal prosecutors in the case: “The accounting fraud that allowed them to move money up into the market-making business (run by Peter, Andrew and Mark) and prop it up, that was in service of obscuring the Ponzi scheme.” (Peter received a 10-year sentence for his involvement.)

Other questions raised by Behar involve Madoff’s wife. “Ruth ‘Ruthie Books’ Madoff. That’s the nickname FBI agents privately gave her,” Behar writes. The author says financial records he uncovered show that Ruth “did plenty of work to maintain some of the critical Ponzi bank accounts for decades after the 1960s — and right up until early 2008.”

All interesting stuff, but, like the other books on Madoff, Behar leads us to no real conclusion. On Ruth, for instance, he concedes that “this does not mean, of course, that Ruth knew it was a Ponzi scheme, specifically, as opposed to just some very shady activity. There is no evidence she did.”

It’s been 16 years since Madoff’s $68bn Ponzi scheme collapsed. Over the years, victims have been getting a percentage of their money back thanks to Picard, who continues to recover “a few tens of millions of dollars at a time” from those investors who withdrew a profit from the fund. Madoff’s estate was seized and sold off.

The fallout has gone beyond financial misery. Some investors who lost money killed themselves, as did Madoff’s son Mark on the two-year anniversary of his father’s arrest. Andrew’s death from cancer came six years after the scam. Ruth is still alive and resides in an assisted-living facility.

Behar’s storytelling and reporting is weakest when he suggests that the Securities and Exchange Commission had good reason to ignore a number of red flags, including those raised by Harry Markopolos, the quantitative analyst who pushed the SEC to investigate Madoff’s investment record before its collapse.

Markopolos, the author writes, “provided no hard evidence” in his initial correspondences with the agency and had “paranoid” tendencies.

Being a longtime newshound, Behar should know most whistleblowers are quirky and paranoid. All the SEC had to do was check if Madoff had done any trading. He hadn’t, of course. But the SEC didn’t check, which should be the final word on the sordid tale of Bernie Madoff.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout